Sexual harassment in the workplace became a public issue somewhat later than sexual violence against women. This was because women additionally had to worry about professional reprisal. The issue spilled over from America to Germany, where feminists broadly took it up. They are soon to be followed by women in trade unions and politics.

1975: USA – Sexual Harassment in the Workplace & Working Women United

In the USA, women start going public about sexual harassment in the workplace. The spark is the case of the administrator Carmita Wood from Ithaca, New York, who resigned from her job because of constant sexual harassment by her boss and is therefore denied unemployment benefits. A group of female students from the local university take up the scandal, establish the group Working Women United, and call on approximately 300 women’s groups and organisations to go public with their experiences of sexual harassment in the workplace. Working Women United are the first to use the term ‘sexual harassment’. The reactions to the appeal are overwhelming. The New York Times headlines: Women Begin to Speak Out Against Sexual Harassment at Work. Soon thereafter, the women’s magazine Redbook determines in a survey that, of the 9,000 respondents, 89% have experienced sexual assault at their workplace.1 (About the history of the term „Sexual Harrassment“ in the USA)

August 1977: Sexual Harassment in the Workplace in Germany

For the first time in the FRG, a victim goes public about her sexual harassment and that of her female colleagues by a superior. In the Frankfurter Rundschau2 and in Courage3, the journalist Annelie Runge reports about incidents of sexual harassment at the large association in which she works as head of the press office. Because of the “never-ending overtures”, working with the managing director has become “torture” for most female employees. Runge and four colleagues report this to the board in an open letter. After the executive board fails to take action, Runge passes the letter on to the press. As a result, she is fired without notice. In the trial that follows, Runge’s termination without notice is withdrawn and Runge obliged to cease criticism of the association in the press. The women had not filed a lawsuit for “indecent assault” because their lawyers had assured them that this was only possible if they could prove that their superior had been violent.4 A law against ’sexual harassment‘ does not exist at this time.

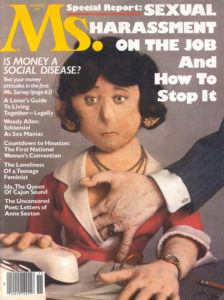

November 1977: Ms. About Sexual Harassment

In the USA, the feminist magazine Ms. headlines: Sexual harassment on the job and how to stop it. The issue is picked up widely by American media.

December 1977: Stern Article and its Reactions

With Angequatscht, Betatscht, Vernascht the Stern takes up the issue of sexual harassment. The magazine introduces eight victims, including Annelie Runge.5 After the article is published, the women – who are mentioned with full name and address – receive obscene calls, insults, and threats.

March 1978: EMMA Article Refers to Stern Reactions

EMMA writes about sexual harassment in the workplace and covers the substantial hostility against Annelie Runge following the publication of her article in the Stern.6

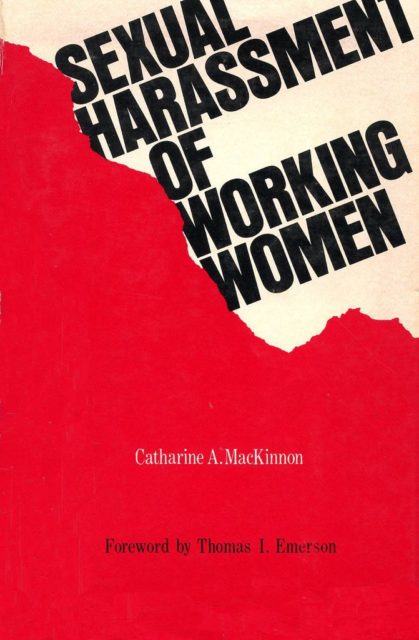

1979: Feminist Analyzes in the USA

Numerous feminist analyzes on the topic of sexual harassment are published in the USA, including Catherine MacKinnon’s Sexual Harassment on Working Women.7 In this seminal book, the lawyer describes the substantial impact of sexual harassment on victims on the basis of testimonies collected by Working Women United. MacKinnon concludes that sexual harassment is an expression of the structural inequality of men and women in the workplace and in society.

November 1980: Sexual Harassment Becomes Part of Article 7 in the US

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) confirms that “sexual harassment” is equivalent to discrimination of the basis of race, gender, and religion; it therefore violates Article 7 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and is grounds for legal action. The term “sexual harassment” is – on the basis of MacKinnon’s suggestions – receives an official definition for the first time. Accordingly, sexual harassment occurs if “consent is an explicit or implicit condition for employment or promotion” and when sexual assault, whether “physical or verbal”, creates “an intimidating, hostile, or offensive atmosphere”.8 Furthermore, the EEOC guidelines contain the provision that employers are responsible and therefore liable for the actions of their employees, irrespective of their status as superiors or colleagues of the victim, if they fail to prevent them.9

December 1980: Definition of Sexual Harassment

Cheryl Benard summarises in EMMA what sexual harassment of women in the workplace means. Bernard refers to analyses by American feminists. Sexual harassment is “less about a truly sexual behaviour, than a demonstration and exercise of power”. Sexual harassment is a “form of intimidation of women”.10

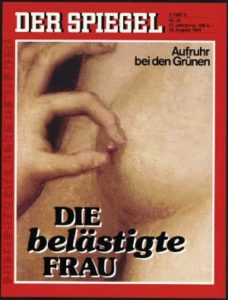

August 1983: „Green bosom friend“ – 1st Big Public Debate

Klaus Hecker, member of parliament for the Greens, triggers the first big public debate about sexual harassment in Germany. The member of parliament had repeatedly grabbed the breasts of female employees in his parliamentary group; the women go public with the assaults, and Hecker is forced to resign.11 EMMA reports about the “Green bosom friend”12, and the Spiegel headlines with the story: Die belästigte Frau. The Spiegel writes: “Almost every working woman experiences sexual harassment – if not herself, then of others – by colleagues or superiors, or simply by men. In this respect, the minor scandal surrounding the Green Member of Parliament Hecker from Bonn, who groped his assistants’ breasts, is only one of thousands of cases.”13 The article refers to a study carried out by Brigitte with 4,200 women working in office jobs. 59% – that is, every two out of three – report that they have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace.

1983: Law against Sexual Harassment Takes Time

The European Parliament declares that in addition to the European “Directive on the Implementation of Equal Opportunities and Equal Treatment of Men and Women in Matters of Employment”, measures against sexual harassment are also necessary. One year later, the EU Council of Ministers calls the member states to action. It will take more than ten years until a law against sexual harassment is passed in Germany.

1984: A Study on the Extent of Sexual Harassment

A study on the extent of sexual harassment, commissioned by the Green Party in the wake of the scandal surrounding Klaus Hecker, is published. Some of the so-called INFAS-Studie findings: every one in four women claim to have been sexually harassed at work once or even several times. In addition, every one in 14 women had lost or quit their jobs because of sexual assault in their workplace.14

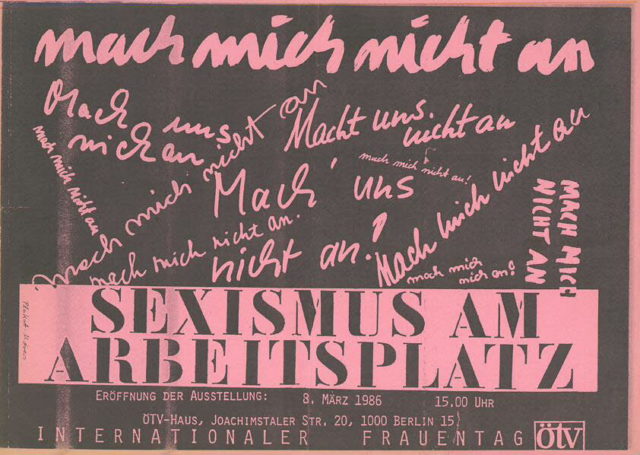

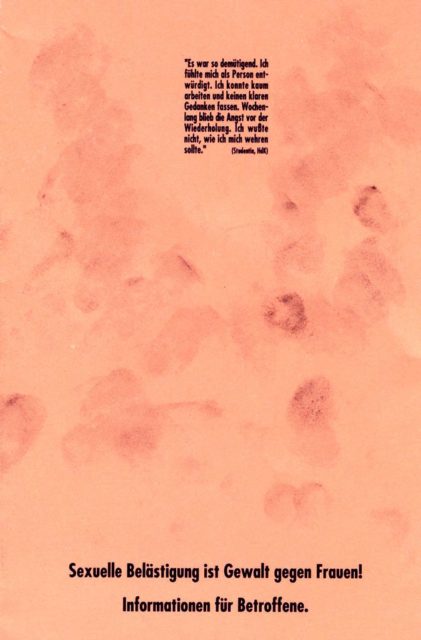

1986: The Issue of Sexual Harassment within German Trade Unions and Universities

Female trade unionists pick up the issue. At the twelfth women’s conference, women working for IG-Metall decide to “make the fight against sexual harassment an integral part of trade union advocacy”.15 The ÖTV–Betriebsfrauenausschuss in Berlin organises the exhibition and poster campaign Mach mich nicht an!16 The Landesfrauenausschuss der Deutschen Angestellten-Gewerkschaft (DAG) Schleswig-Holstein calls on works and staff councils to establish a “complaints office for sexual harassment”.17

The Internationale Bund Freier Gewerkschaften (IBFG) calls on all affiliates to “develop a clear political line on the issue of sexual harassment in the workplace”, and in December it publishes the first trade-union guide to dealing with the issue.18 The broschure “Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz: Frauen wehren sich” published by the DGB the following year introduces the issue of sexual harassment within German trade unions, and it contains the observation that currently unions are themselves in need of training on this issue.19

11 years after the Americans, academics at German universities now also become active. For example, an Arbeitsgemeinschaft Sexuelle Belästigung von Frauen an den Hochschulen is established at the FU in Berlin after the sexual harassment of students by a professor became public.20 Following the American model, a catalogue concerned with the “definition and guidelines for sexual harassment at universities” is developed, on which the president of the university is to comment. The German-American professor Carol Hagemann-White is designated the contact person for victims of sexual harassment.21

![Holzbrecher, Monika ; Braszeit, Anne ; Müller, Ursula ; Plogstedt, Sibylle (1990): Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz. - Stuttgart [u.a.] : Kohlhammer (FMT-Signatur: AR.03.405) Holzbrecher, Monika ; Braszeit, Anne ; Müller, Ursula ; Plogstedt, Sibylle (1990): Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz. - Stuttgart [u.a.] : Kohlhammer (FMT-shelfmark: AR.03.405)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Holzbrecher_Sexuelle_Belaestigung_am_Arbeitsplatz.jpg)

March 1986: A Draft Anti-Discrimination Law

The Green Party presents a draft anti-discrimination law. It is intended to document the basic legal elements of the sexual harassment crime for the first time. Women who want to defend themselves against sexual harassment only have the option to sue for indecent assault, blackmail, and abuse of a dependent. Article 1 of the draft’s comprehensive clause states that “the unequal treatment and discrimination of a women based on her gender (…) is not permitted”. What is meant by discrimination is, however, only explained in general terms in Paragraph 3. Whether sexual harassment of women in the workplace can be included under this definition is left to judicial interpretation.22

20 May 1986: Definition and Information Campaigns

The Committee on Women’s Rights and Gender Equality presents a report about violence against women to European Parliament that mentions the problem of sexual harassment. As a result, the EU Parliament calls on EU countries “to seek a legal definition of sexual harassment, so that victims of such advances have a clear basis on which to file a complaint”. It also calls for widespread information campaigns by governments and unions with the aim “to educate all employees about their individual rights, to highlight the discriminatory nature of sexual harassment, and to educate victims about the options available to them”.23 The issue is to be addressed in the context of sex education and social studies in schools.

August 1986: A Study about Sexual Harassment

The Minister for Women’s Affairs Rita Süssmuth (CDU) announces that she intends to commission a study about sexual harassment of women in the workplace. In addition to surveying the extent of the problem, case-law is to be evaluated and proposals for protective measures developed. The study will be published in 1991.

1989: 15 Months in Prison “for Constant Sexual Harassment”

A judge in Hannover sentences the head of a private ambulance service to 15 months in prison “for constant sexual harassment”. The 45-year-old had badgered and groped his 22-year-old secretary for months. The Spiegel regards the “unprecedented high punishment” as “an indication that the judiciary now assesses the criminal significance of sexist assault in the workplace differently than it has in the past”.24

What Happens Next?

In 1991, the Federal Minister for Women Angela Merkel presents the study announced by her predecessor. It confirms that there is a sexual harassment epidemic: every three in four women have experienced sexual harassment in the workplace. Every second victim reports being subjected to sexually suggestive remarks. Every one in five has had their breasts touched. And every one in ten has been propositioned by their boss or a male colleague. Most exposed to unwanted sexual advances are women in so-called “male professions”, with female police officers the worst affected.25

One year later, the Minister for Women Merkel presents the draft for a law intended to combat sexual harassment in the workplace and reaps plenty of scorn from the media for it. The Bild am Sonntag publishes a disadvantageous snapshot of Merkel and mocks: “Would you employ this woman?”.26

On 1 September 1994, the Gesetz zum Schutz der Beschäftigten vor sexueller Belästigung comes into force in Germany. It defines sexual harassment as “any intentional, sexual behaviour that violates the dignity of employees in the workplace”. It covers not only established criminal offences like indecent assault, but also “requests for sex acts” and the “affixing of pornographic representations”. In addition, employers have a duty to protect employees from sexual harassment. If employers fail to act, the employee concerned (female and male, although the latter is a much rarer occurrence) can cease work and sue the employer. Despite this law, cases of sexual harassment still come to public attention, especially with respect to women in ‘male’ professions.

On 14 February 1999, the police officer Silvia Braun from Munich shoots herself with her service weapon. Reason: substantial bullying by her department.27 The police union describes the case, which receives national news coverage, as “the tip of the iceberg”. After the admission of women to the Bundeswehr on 1 January 2001, cases of rape at army barracks are also reported (see also our text on women in the military).

On 14 August 2006, the Allgemeine Gleichbehandlungsgesetz (AGG) comes into force as a result of pressure from the EU, which had passed a number of equality directives between 2000 and 2004. The aim of the AGG is to “prevent or eliminate discrimination based on racial or ethnic origin, gender, religion or world view, disability, age, or sexual identity”. The AGG applies not only to discrimination in the workplace, but also to so-called “Massengeschäfte” [legal transactions] like leases or insurances. The law replaces the previous Gesetz zum Schutz der Beschäftigten vor sexueller Belästigung and contains the same provisions.

The arrest of Dominique Strauss-Kahn on 14 May 2011 shocks the world. Nafissatou Diallo, a maid from Guinea, accuses the member of the Parti sozialiste and acting head of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) of having forced her to perform oral sex at the New York Sofitel hotel. Strauss-Kahn denies the allegations and is acquitted at trial. However, he later pays Diallo a sum in the millions to prevent a civil suit. Soon other women in France speak out and accuse Strauss-Khan – who regularly participated in ‘sex parties’ with forced prostitutes – of sexual assault. The Strauss-Kahn case becomes the prime example of the principle of omertà, i.e. of the code of silence that prevailed despite general knowledge of the politician’s sex assaults. In 2016, 17 politicians – including Strauss-Kahn’s successor Christine Lagarde – speak out with the appeal: “We will not remain silent!”

On 24 January 2013 – in the year of the general election – the Stern publishes Der Herrenwitz28, a portrait of the FDP’s top candidate Rainer Brüderle by the reporter Laura Himmelreich. In her article, Himmelreich describes the 67-year-old’s sexist insults and asks if a politician who has such a (misogynistic) perception of women is electable. That sexist behaviour is not seen as trivial, but rather taken seriously as a potentially disqualifying aspect for a politician is a new development. The Brüderle case is discussed across Germany; the media reports and debates nationwide.

One day later, internet activists in Berlin begin using the hashtag #aufschrei and call on women to describe their experiences of sexual harassment. Thousands respond to the appeal and report their experiences in tens of thousands of tweets; the media and talk shows provide non-stop coverage of the phenomenon. The overwhelming response demonstrates that sexism and sexual assault in – but not restricted to – the workplace are still the order of the day for girls and women.29

After thousands of men of North African/Arab origin attack women on a massive scale at Cologne’s central station on New Year’s Eve 2015/2016 by deliberately groping their breasts, bottoms, and genitals, the general public becomes aware that these offences are practically impossible to punish under existing criminal law. So-called ‘Grapschen’ or ‘groping’ – whether in the workplace or in a public space – was not classed as “sexual harassment” by the courts because it fell under the “critical threshold”. A widespread public debate about this gap in penal law begins.

![Tatort Arbeitsplatz : sexuelle Belästigung von Frauen (1992). - Gerhart, Ulrike [Hrsg.] ; Heiliger, Anita [Hrsg.] ; Stehr, Annette [Hrsg.]. 1. Aufl. - München : Frauenoffensive (FMT-Signatur: AR.03.046). Tatort Arbeitsplatz : sexuelle Belästigung von Frauen (1992). - Gerhart, Ulrike [Hrsg.] ; Heiliger, Anita [Hrsg.] ; Stehr, Annette [Hrsg.]. 1. Aufl. - München : Frauenoffensive (FMT-shelfmark: AR.03.046).](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Gerhart_Tatort_Arbeitsplatz-396x640.jpg)

On 7 July 2016, the Bundestag passes a reform of sex crime legislation. The newly created §184i “sexual harassment” reads: “Whoever physically touches – and thereby harasses – another person in a sexual manner will be punished with a prison sentence of up to two years or a fine.” (full legal text) Sexual harassment is thus – four years after the women’s movement went public with the problem – no longer exclusively anchored in the AGG, but also punishable by law.

References

1 Cited in: Cadalbert Schmid, Yolanda (1988): Lästige Aufmerksamkeiten : sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz, in: Emanzipation : feministische Zeitschrift für kritische Frauen, Bd. 14, Heft 4.

2 Runge, Annelie (1977): Sex-Angebote am Schreibtisch : Zu einem „Offenen Brief“ an den Chef. – In: Frankfurter Rundschau, 20.8.1977, see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz I (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-AR.03.07, Kapitel 1).

3 Runge, Annelie (1977): Wenn mein Chef mit mir schlafen will. – In: Courage 9/77, see Pressedokumentation I : Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-AR.03.07, Kapitel 1).

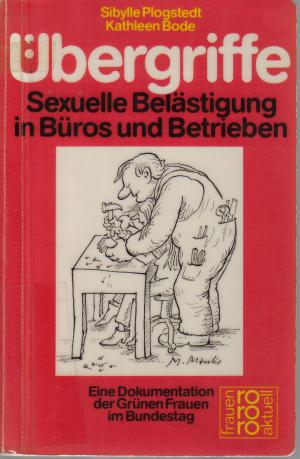

4 Plogstedt, Sibylle; Bode, Kathleen (1984): Übergriffe. Sexuelle Belästigung in Büros und Betrieben. Reinbek bei Hamburg, p. 131f. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.045).

5 Kolb, Ingrid (1977): Angequatscht, Betatscht, Vernascht. – In: Stern, 8.12.1977, see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz I (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-AR.03.07, Kapitel 1).

6 Ferkel im Betrieb. - In: EMMA, 3/1978, p. 50, see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz I (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-AR.03.07, Kapitel 1).

7 MacKinnon, Catharine: Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Discrimination. - Yale Univ. Press 1979. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.050)

8 Roques, Valeska (1983): Ich möchte mich gerne wehren, aber wie?. - In: Spiegel, Nr. 33, p. 81. (15.08.)

9 Hohmann, Harald ; Moors, Christiane (1995): Schutz vor sexueller Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz im Recht der USA (und Deutschlands). In: Kritische Justiz, Vol. 28, Nr. 2, p. 154.

10 Benard, Cheryl (1980): Immer nur lächeln. Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz. - In: EMMA, Nr. 12, p. 25.

11 For more information about the „Hecker-case“ see: Pressedokumentation im FMT: Sexuelle Gewalt in Abhängigkeitsverhältnissen, exemplarische Fälle 1975-1993 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.02, Kapitel 7).

12 Grüner Busenfreund. Sexuelle Belästigung (1983) - In: EMMA, Nr. 9, p. 13.

13 Von Roques, Valeska (1983) „Ich möchte mich gerne wehren, aber wie?“. - In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 33, p. 81.

14 For a summary of the results see: Plogstedt, Sibylle; Bode, Kathleen (1984): Übergriffe. Sexuelle Belästigung in Büros und Betrieben. Reinbek bei Hamburg, p. 98f. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.045).

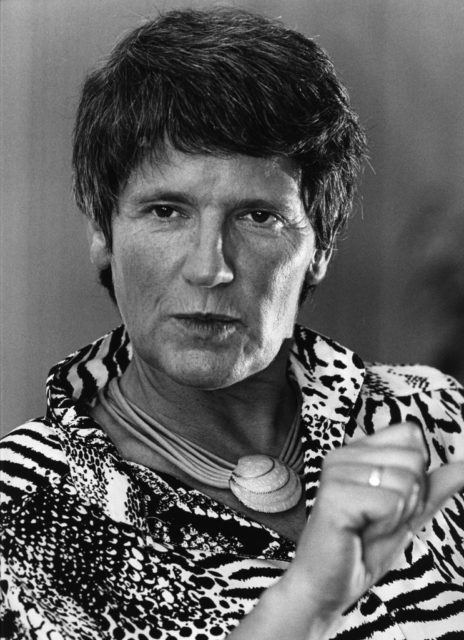

15 Schwarzer, Alice (Hrsg.): Es reicht! Gegen Sexismus im Beruf. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Köln 2013, p. 161. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.411).

16 Bezirksfrauenausschuss der ÖTV Berlin (Hrsg.) (1986): Mach mich nicht an : Sexismus am Arbeitsplatz ; Dokumentation einer Ausstellung,. – Verlag Die Arbeitswelt , Berlin (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.020).

17 Angrapschzeit (1986). - In: Kofra : Zeitschrift für Feminismus und Arbeit, Heft 25, p. 27.

18 Internationaler Bund freier Gewerkschaften (IBFG)(1986): Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz

beseitigen. Ein Leitfaden für Gewerkschaften. - Brüssel.

19 DGB-Bundesvorstand Abteilung Frauen und Abteilung Jugend (1987): Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz : Frauen wehren sich. – Düsseldorf. (FMT Shelf Mark der 2. Auflage: AR.03.049).

20 Krüger, Petra (1988): Bumerang. – In: EMMA, Nr. 9, pp. 40 - 41.

21 Hentschel, Gitti (1986): Wenn der Herr Professor grabscht. – In: Die Tageszeitung, 3.5.86, see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz I (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-AR.03.07, Kapitel 1).

22 Slupik, Vera (1986): Grüne Frauen gegen Männerfront. – In: EMMA, Nr. 3, pp. 4 – 6.

23 Ancona, Hedy de; Europäisches Parlament / Ausschuss für die Rechte der Frau [Hrsg.]. (1986): Bericht im Namen des Ausschusses für die Rechte der Frau über Gewalt gegen Frauen. (Dok. A2-44/86) - Straßburg. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.01.033).

24 Schwarzer Schwarzer, Alice (Hrsg.): Es reicht! Gegen Sexismus im Beruf. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Köln 2013, S. 162. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.411). See auch Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz II (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-AR.03.08, Kapitel 3).

25 Holzbrecher, Monika ; Braszeit, Anne ; Müller, Ursula ; Plogstedt, Sibylle (1990): Sexuelle

Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz. - Stuttgart [u.a.] : Kohlhammer (Schriftenreihe / Bundesminister für Jugend, Familie und Gesundheit ; 260). (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.405).

26 Königin ohne Land : Mit ihrem Gesetz zur Gleichberechtigung stößt Frauenministerin Angela Merkel auf Widerstand (1992). - In: Der Spiegel, Heft 10, p. 107. Retrieved from:http://magazin.spiegel.de/EpubDelivery/spiegel/pdf/13681420

27 Musall, Bettina ; Ulrich, Andreas (1999): Ganz ungeniert : Polizistinnen werden von Kollegen häufiger sexuell belästigt als Frauen in jedem anderen Beruf. Jetzt hat sich eine Beamtin umgebracht. – In: Der Spiegel, Heft 8, p. 83.

28 Himmelreich, Laura (2013): Der Herrenwitz. – In: Stern, 24.1.2013.

29 Hollstein, Miriam (2014): Das große Schweigen? Was vom #aufschrei übrig blieb. In: Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung (Dossier Sexismus). Retrieved from: www.bpb.de/apuz/178662/was-vom-aufschrei-uebrig-blieb

All internet links were last accessed on 01.03.2018.

Selective Bibliography

Documents online

Arbeitsschutzgesetz.org (2017): Sexuelle Belästigung am Arbeitsplatz erkennen und darauf reagieren.

Recommendations

MacKinnon, Catharine (1979): Sexual Harassment of Working Women: A Case of Discrimination. - Yale Univ. Press (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.050).

Tatort Arbeitsplatz : sexuelle Belästigung von Frauen (1992). - Gerhart, Ulrike [Hrsg.] ; Heiliger,

Anita [Hrsg.] ; Stehr, Annette [Hrsg.]. 1. Aufl. - München : Frauenoffensive (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.046).

Schnock, Brigitte (1999): Die Gewalt der Verachtung : sexuelle Belästigung von Frauen am

Arbeitsplatz. - St. Ingbert : Röhrig Univ.-Verl (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.059).

MacKinnon, Catharine (2005): Women's lives, men's laws. - Cambridge, Mass. [u.a.] : Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.10.050).

Es reicht! Gegen Sexismus im Beruf (2013). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Kiepenheuer & Witsch, S. 161 (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.03.411).

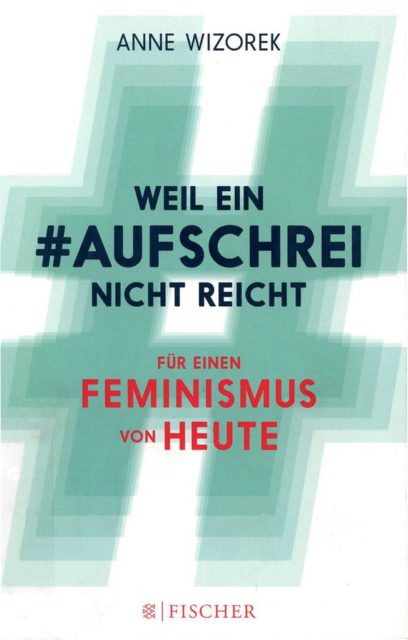

Wizorek, Anne (2014): Weil ein #Aufschrei nicht reicht : für einen Feminismus von heute. - Frankfurt am Main : Fischer (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.10.207).

FMT Press Documentation

Press Documentation on Sexual Harassment: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Selected FMT-Sources (lists)

FMT literature selection Sexual Harassment: PDF-Download

EMMA article Sexual Harassment: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Women's Refuges - Protection from (Sexual) Violence

Women's Refuges - Protection from (Sexual) Violence

Beginning in the mid-70s, the women’s movement made the dramatic extent of violence by men against their own wives and children public and launched the first women’s refuges. › mehr

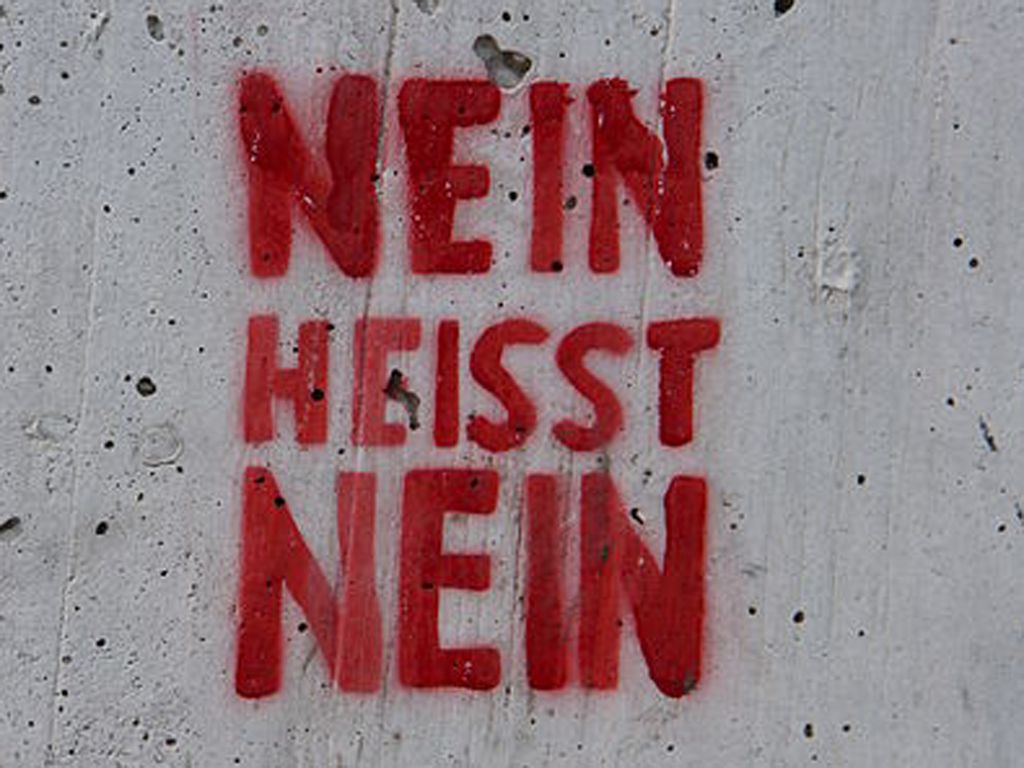

Fighting Sexual Violence and (Marital) Rape

Fighting Sexual Violence and (Marital) Rape

In the mid-1970s, the women’s movement brought the epidemic of sexual violence to the public’s attention. The women fought for a sex crime law reform, that finally came through 1997 and 2016. In Germany today the principle rules: No means No. › mehr

Sexual Abuse - When Crime Begins Within the Family

Sexual Abuse - When Crime Begins Within the Family

In 1978 feminist magazine EMMA first broke the silence of a long-held taboo: sexual abuse. 5 years later the self-help group Wildwasser and the first girls’ refuge were established. › mehr