Pornography is not a new phenomenon. However, with the emergence of the New Women’s Movement, it reached new dimensions, both quantitatively and qualitatively. With the advent of new media, pornography even achieved a certain ubiquity. The feminist debate about pornography is as divided as the debate about prostitution. The battle lines are virtually identical. Many left-wing feminists consider pornography to be unproblematic, whereas most autonomous feminists oppose pornography as verbal and visual sexual violence, as ‘sexualised misogyny’. The latter’s definition of pornography – as propagated in Germany by EMMA, a pioneer in the anti-pornography struggle – reads: pornography combines sexual desire with the sheer pleasure of causing humiliation and pain.

1972: The Film Deep Throat with Linda Lovelace

Deep Throat1 – probably still the most famous porn film in the Western world – is released in the USA. The film is considered a direct response to the American women’s movement, which from the late 1960s had become a powerful social force. Deep Throat (plot: a sexually frustrated woman discovers that her clitoris is located in her throat) took the porno from adult movie theatres into mainstream culture, ultimately making pornography ‘chic’.

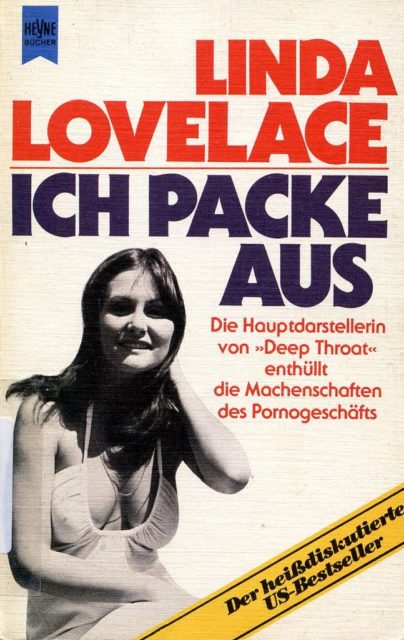

The film – showings of which are demonstrably attended by celebrities – makes 600 million dollars. Feminists protest in front of movie theatres. Eight years after filming, the lead actress Linda Lovelace describes in her autobiography Ordeal2 under what conditions Deep Throat was filmed: Lovelace (born Linda Boreman) was badly abused by her ‘partner’ Chuck Traynor, brutally forced into prostitution by him and into her role in Deep Throat. The film crew knew about the abuse, but didn’t intervene. Linda Boreman joins up with feminists as a campaigner and key witness against the porn industry.

7 June 1973: 4th Sex Crime Legislation Reform

The German Bundestag passes the fourth sex crime legislation reform with votes from the social-liberal coalition – and against CDU/CSU votes – that provides for the deregulation of ‘basic’ pornography for adults. Pornographic content involving ‘acts of violence’, sex acts with animals, and child pornography continues to be prohibited. Furthermore, pornographic images are not to be made available to minors, i.e. children under the age of 18. The German women’s movement at first doesn’t react to the reform, which comes into force on 27 January 1975.

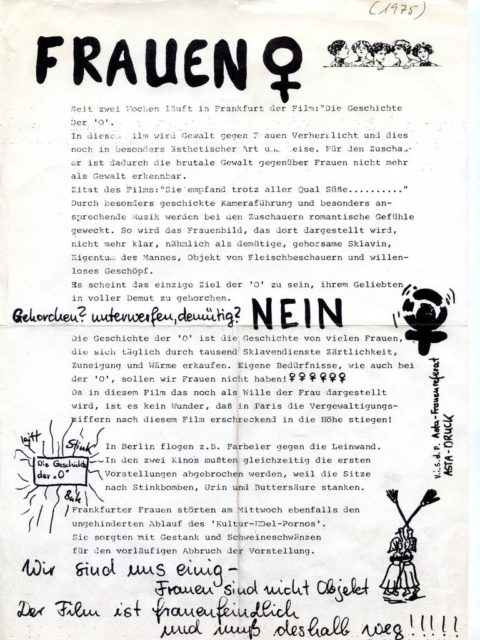

November 1975: 1st Women’s Protest

The film Geschichte der O3 – based on the book by Pauline Réage (actually: Anne Desclos) – is released in cinemas. The film is about a woman who, her identity stolen by her lover, becomes a sex slave in a castle and finds fulfilment in submitting to men’s sadistic wishes. Women’s groups in Aachen, Berlin, Bonn, and Frankfurt am Main storm cinemas with stink bombs and spray paint cans, throw eggs at the screen, and thus ensure that many screenings have to be cancelled. They bring charges for “trivialising violence” and “violating the law against violent pornography”. These are the first women’s protests against pornography in Germany.

23 July 1977: 1st Reprimand for Sexism

For the first time in the history of the German press, the Deutscher Presserat issues a reprimand for sexism.4 The Spiegel had illustrated a cover story about child pornography with the photo of a 12-year-old wearing nothing but suspenders. The child is Eva Ionesco. Eva Ionesco is marketed as a nude model by her mother, the photographer Irina Ionesco. Ionesco will reflect on her story in the 2011 feature film I’m not a F***ing Princess5 and sue her mother for 200,000 euros in damages and the return of all nude photos.6 The Spiegel’s headline reads: Kinder auf dem Sex-Markt – Die verkauften Lolitas. EMMA, Courage, Unsere kleine Zeitung, and the Kinderschutzbund raise objections with the Presserat about the use of this photo on the cover: “An image that would as such be offered in a pornographic publication is in this case subject of mockery and morally masked.” The Presserat denounces that “a child is pictured as a sexual object in such a striking manner.”

January 1978: Attacks by the Militant Rote Zora

The militant Rote Zora attacks six Dr. Müller’s Sexshops in Cologne and steals pornographic products worth 200,000 DM. In an anonymous pamphlet, the group – which is committed to the aims of the autonomous women’s movement – declares: “We’re so fed up with these shops. Women are reduced to their bodies – degraded as sex machines available at the buyer’s convenience […]. The porno industry’s most recent achievements – peep shows and topless booths – are sold to us as emancipatory advances. The acts of violence we experience every day on the street are in sharp contrast to the generally accepted argument that the deregulation of pornography helps reduce violence against women.” Slogan: “Mit List und Tücke hauen wir die Pornoshops in Stücke!”. In the meantime, in Germany alone the porno industry turns over a profit of 1.1 billion DM annually.

23 June 1978: The Stern Lawsuit – the Claim

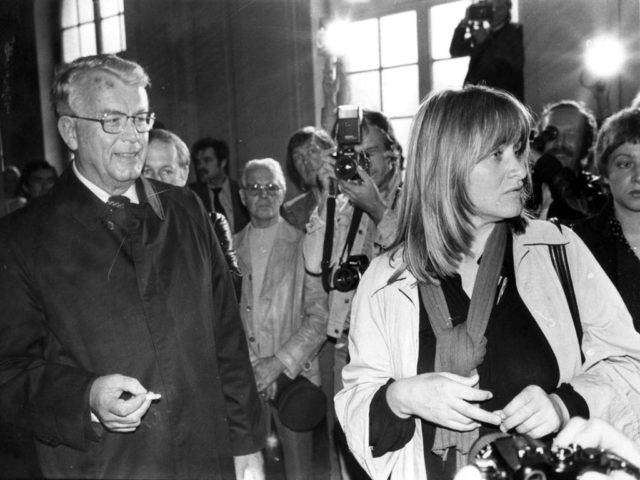

At the district court in Hamburg, nine women – including Inge Meysel, Erika Pluhar, Margarete Mitscherlich, and Margarete von Trotta – join a lawsuit initiated by Alice Schwarzer to contest sexist cover images published by the Stern magazine. Their lawyer Dr. Gisela Wild calls for the “defendants to be ordered to refrain from offending the plaintiffs by portraying women as mere sexual objects on the cover pages of the Stern, thereby giving male readers the impression that they are able to dispose of and dominate women at will.” In the case of any infringement, the defendants are to pay a fine of up to 500,000 DM. The application states: “The representation of women is utterly depersonalised in these images, which reduce women to sexual playthings. Female inferiority and male dominance are thus simultaneously articulated. The defendants may refer to the fact that they first and foremost chose images of women’s bodies that were aesthetically beautiful; they may argue that acknowledgement of nakedness and sexuality is part of women’s emancipation – but that’s not the question here. What is most important here is that women are portrayed as though available for male desire all the time and therefore under men’s control.”

The plaintiffs know that they cannot legally win the case because there is (still) no legal basis under criminal or civil law to prosecute sexist representations of women. In fact, they want to draw attention to this legal loophole and to sensitise the public to the seemingly self-evident portrayal of women as sex objects. The entirety of the Deutscher Frauenrat – the umbrella organisation for the German women’s associations that has six million members – endorses the lawsuit.

26 July 1978: The Stern Lawsuit – the Judgment

The charges are dismissed. However, the court justifies the dismissal – as expected – on purely formal grounds. First, there is the question of whether the ten plaintiffs are even allowed to press charges in the name of a “greater group” of women. In the charge, Wild states: “Each plaintiff, as a member of the social group of women, is personally affected, and their honour insulted by the cover images […] The women who now live in Germany also form a majority of persons that is capable of being insulted and through insult to this plurality, each single member’s honour is offended.” The court denies the claim: there is no “direct attack on the plaintiffs’ rights.”

With respect to the plaintiffs’ concerns on sexual politics, Judge Engelschall declares: “The chamber recognises that working towards a representation of women in the public sphere – and especially in the media – that is commensurate with the real position of women in society can be a legitimate agenda.” However, “the courts are not responsible” for this. The plaintiffs must “turn to the legislature” with their concerns. And: “In 20 or 30 years, the plaintiffs may well win.”

The Stern lawsuit is in the headlines for months, touching the nation and contributing significantly to increased public awareness of everyday sexism.

7 December 1978: Press Code Reform

The Deutscher Presserat adds ‘gender’ to their press code. From now on, the code reads: “No one is to be discriminated against because of gender or belonging to a racial, religious, or national group.” The self-regulatory body had accepted the application by EMMA’s editorial board – made in the course of the Stern lawsuit – to supplement the press codex. The Presserat states: “In its session on 4 October 1978, the Deutscher Presserat rejected the charges against the Stern’s four cover images as unfounded. However, these complaints are taken as an opportunity to pass on the suggestions to the press, that today’s self-image of women in society should be taken into account.”

1979: Women Against Pornography

The initiative Women Against Pornography (WAP) is established in New York; founding members include Gloria Steinem, Susan Brownmiller, Adrienne Rich, Shere Hite, Andrea Dworkin, and Catharine MacKinnon. Women Against Pornography quickly grows to be influential: the group first becomes a talking point with anti-pornography campaigns in sex shops and adult movie theatres as well as a march on Times Square that is attended by several thousand activists. Later, especially the activist Dworkin and the lawyer MacKinnon will develop draft legislation that aims to put an end to the humiliation and degradation of women in pornography.

They distinguish between erotic depictions that assume ‘reciprocity and reversibility’ and pornographic depictions that they define as violating women’s civil rights and human dignity.7

December 1979: Not an Issue of the Law and Police?

The struggle against the humiliating and degrading portrayal of women in pornography is also a key issue within the women’s movement in Germany. In an open letter, an anti-pornography women’s group from Cologne calls on the Minister for Family Affairs Antje Huber (SPD) to join the group on a tour of sex shops and to open her eyes to the “unbelievable brutality […] with which women’s human dignity is violated”. The initiative, to which the artist Ulrike Rosenbach belongs, declares: “The liberalisation of sex that has taken place since the 1950s has been at the woman’s expense; permissiveness towards pornographic material has only strengthened the sexual manipulation of femininity for commercial purposes.”8 The minister refuses with the argument that, although “she agrees that the majority of products produced by the porn industry represent women as always available objects”, but she “takes a dim view of direct state intervention by way of the law and police.”

1986: Photo Series Commented by A. Schwarzer

The Austrian lifestyle magazine Wiener, which from 1986 also has a German edition, publishes a photo series entitled Zeitgeist that consists of sadistic pictures of women who have been tied-up and tortured. The magazine characterises these “male fantasies” as “a petty bourgeois dream”. Alice Schwarzer sees the series as a reaction by ‘new men’ to the ‘new women’. She writes: “It is no longer enough for them to depict us in fishnet stockings, cleavage, and bunny ears. They tie us up. They torture us. They murder us. Because that’s what turns this new man on: a cold, dead woman. He’s had enough of emancipation.” And Schwarzer announces: “We’re not going to accept this. We have to seriously ask ourselves what can be done. And we will know how to respond.”

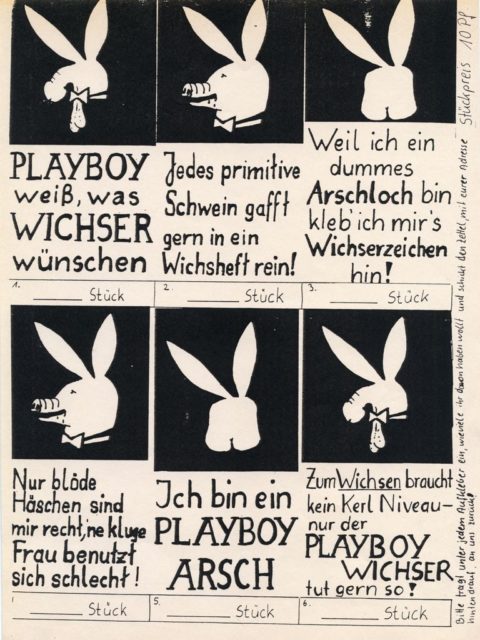

October 1987: PorNo Campaign

EMMA launches the campaign PorNO. In its October issue, the magazine laments the pornographisation of all areas of society and the escalation of pornographic violence (“each month 500,000 porn videos are rented, 200,000 of these are ‘particularly violent’”). EMMA defines its criteria for pornography: “‘Pornographic’ representations are representations created for sexual arousal that humiliate women, that portray them in a position of powerlessness relative to men, and that incite the hatred or even murder of women.” EMMA documents research about the clear link between pornography and violence, and the magazine exposes the degrading working conditions of porn ‘actresses’. Andrea Dworkin’s Pornography – Men Posessing Women9 (1981) is published in German translation as Pornographie – Männer beherrschen Frauen10 with EMMA-Verlag.

25 November 1987: Draft Legislation of Pornography

In collaboration with the future Senator of Justice Lore Maria Peschel-Gutzeit (SPD) in Hamburg and Berlin, Alice Schwarzer develops draft legislation that designed to be effective against misogynistic pornography. Schwarzer sends the draft to all members of parliament as well as to the Minister of Justice Hans Engelhard (FDP) and the Minister for Family Affairs Rita Süssmuth (CDU). Up until now, the legislature had defined pornography as representations “intended to stimulate sexual arousal in the viewer and thereby clearly exceed the limits of general social decency.”

The draft legislation published in EMMA defines pornography in §2 thus: “Pornography is the trivialising or glamourising, clearly demeaning representation of women or girls in pictures and/or writing.” Elements include the enjoyment of “humiliation, injury, or pain”, rape, or when the women/girls portrayed as sex objects are “tied up, beaten, injured, abused, mutilated, cut up, or otherwise the victims of coercion and violence”. Furthermore, the draft legislation aims to close the loophole that was uncovered by the Stern trial. In §3, the draft demands: “Every woman who is confronted with a pornographic representation is entitled to assert her rights.”

26 November 1987: Women Against Pornography?

EMMA organises a panel discussion on the topic Frauen gegen Pornographie? at the Volkshochschul-Forum in Cologne. Rita Süssmuth (CDU), Renate Schmidt (SPD), Alice Schwarzer, and further supporters of the anti-pornography campaign discuss EMMA’s draft legislation and the book by the anti-pornography activist Andrea Dworkin, who is also present. Verena Krieger (Green Party), Markus Peichl (editor-in-chief of TEMPO), and Hellmuth Karasek (editor-in-chief of the Spiegel’s feuilleton) also sit on the panel. Karasek summarises the results of the discussion from his point of view: “We do not know exactly what beast we have unleashed with this law, we only know that things cannot go on as they are.”11

12-13 September 1988: Organised Hearing on Pornography

On the initiative of the member of parliament Renate Schmidt, the SPD organises a hearing on the subject in Bonn which – however – comes to nothing. Four out of the five legal experts present are in favour of a ,Verbandsklage‚ [legal actions taken by associations]. Accordingly, a society – i.e., a legal association comprising at least seven people – is allowed to file a lawsuit if the protection of women from pornography is enshrined in their statues.

The draft legislation and the campaign trigger a general social debate about the consequences of pornography.

What Happens Next?

In 1998, a bipartisan alliance of female politicians – to which the ministers Lore Maria Peschel-Gutzeit and Ulla Schmidt (SPD), Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger (FDP), and the Speaker of the House Rita Süssmuth (CDU) as well as Rita Grieshaber (Green Party) belong – takes up the PorNO discussion. They call for a new version of the pornography law and the inclusion of the category ‘misogyny’ in the hate speech law in EMMA. After the parliamentary elections in Autumn 1998, the new Minister of Justice Herta Däubler-Gmelin (SPD) announces an “overdue anti-porn law”. After Däubler-Gmelin’s unexpected resignation, her successor Brigitte Zypries does not pick the project up. – To date, ‘misogyny’ is neither a legal category, nor is there an adequate law against pornography.

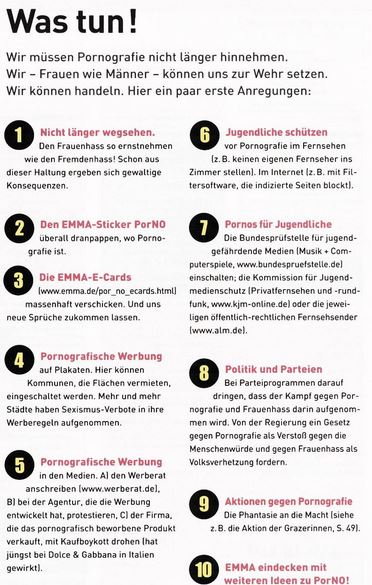

In 2007, EMMA launches the third phase of their PorNO campaign. The growth of new media – above all, the internet – has substantially increased the dissemination of pornography.13 Consumers of pornography are getting younger and younger.14 Scientists sound the alarm. According to the Munich neuropsychologist Prof. Henner Ertel: “Emotional intelligence and empathy have decreased substantially among young people. Sexuality is today inextricably linked with violence not only for the majority of young men, but also for many young women.”15 Prof. Klaus Beier – head of the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft at the Charité hospital in Berlin – “is worried about the ease with which all manner of pornographic images and films – involving sexual contact with animals, acts of humiliation, the infliction of pain and injuries – can be accessed.” Beier characterises the confrontation of in particular young people with pornographic material available on the internet as an “unethical human experiment”.16

In 2009, the Minister for Family Affairs Ursula von der Leyen launches a bid to push through a law that would block child pornography websites. After massive protests (“Zensursula”) by left-wing internet activists, the law is passed but the Bundestag decides not to enforce it. A legal precedent.17

Just like prostitution, pornography is a billion dollar business. In 2015 alone, it had a global turnover of 70 billion euros, 5.3 billion of which took place in Germany.18

The two sectors overlap: women who work as prostitutes are frequently also porn actresses – or porn actresses descend into prostitution. And the same people are making the money. The under-the-counter pornography of the past has long been replaced worldwide by internet pornography available to everyone. The brutality of pornography continues to escalate because of increased desensitisation. Feminist protest against pornography – accused of “prudery” – is not currently on the offensive. Pornography and the pornographisation of culture, fashion, and the media is omnipresent and has not only gotten into the heads of men, but also of some women.

In April 2016, the Minister of Justice Heiko Maas (SPD) announces a law against sexist advertising. Representations that “reduce [women or men] to sexual objects” are to be prohibited. There is substantial media and political protest. The leader of the FDP Christian Lindner talks of censorship and the “nanny state”.19

References

1 Damiano, Gerard: Deep Throat (1972). - USA, Film.

2 Lovelace, Linda ; MacGrady, Mike (1980): Ich packe aus. - München: Heyne (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.09.039).

3 Jaeckin, Jack: Geschichte der O (1975). - Frankreich, Film.

4 Frauen klagen gegen den Stern: Polit- und Pornopresse (1978). - In: Emma, Nr. 10, p.14f.. Retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45153

5 Ionesco, Eva: I’m not a F***ing Princess (2010). - Rumänien/Frankreich, Film.

6 Frank, Charlotte (2011): Von der nackten Prinzessin : Die Lebensgeschichte der Regisseurin Eva Ionesco. – In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 29.10.2011. Retrieved from: www.sueddeutsche.de/leben/lebensgeschichte-der-regisseurin-eva-ionesco-von-der-nackten-prinzessin-1.1176396

7 Dworkin, Andrea (1987): Pornographie : Männer beherrschen Frauen. Köln: EMMA-Frauen-Verlag, p. 14. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.09.014-1987).

8 Die Chronik der Frauenbewegung (2012). - Emma Online, 01.01.2017. Retrieved from: www.emma.de/artikel/die-chronik-der-frauenbewegung-265834

9 Dworkin, Andrea (1981): Pornography : Men Posessing Women. - New York : Putnam (FMT Shelf Mark FE.09.014-1981).

10 Dworkin, Andrea (1987): Pornographie : Männer beherrschen Frauen. - Köln : Emma-Frauen-Verlag (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.09.014-1987).

11 Lukoschat, Helga ; Neef, Uthoff, Maria (1989): De Sade schuf Verwirrung auf dem Podium. - In: Die Tageszeitung, 28.11.1987, see Pressedokumentation: Pressereaktionen auf die PorNo-Kampagne I, 1987-1989 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.09.04).

12 See Pressedokumentation: Pressereaktionen auf die PorNo-Kampagne I 1987-1989 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.09.04).

13 In 2007, pornography accounts for 13% of all internet traffic in Germany and therefore takes third place after film and television. These figures stem from the internet study Ipoquo, which is cited in the following publication: Grimm, Petra ; Rhein, Stefanie ; Müller, Michael (2011): Porno im Web 2.0. - Berlin : Vistas Verlag, p. 13 (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.09.064).

14 A 2008 study reveals that in Germany 45.5% of adolescents between the ages of 16 and 19 consume pornography at least once a month, and of this group, 9.9% consume pornography daily. Ibid., p. 28 (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.09.064).

15 Schwarzer, Alice (2009): Die Tat eines Frauenhassers. - In: Die Welt (16.03.2009). Retrieved from: www.welt.de/welt_print/article3382633/Die-Tat-eines-Frauenhassers.html

16 Ein unethischer Menschenversuch : Interview mit Prof. Dr. Klaus M. Beier (2010). - In: Frankfurter Rundschau, 12.05.2010. Retrieved from: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/inland/im-gespraech-klaus-beier-ueber-kinderpornographie-ein-grosser-unethischer-menschenversuch-1981539.html

17 Reißmann, Ole (2009): Stoppschild für Zensursula. - Spiegel Online (16.10.2009). Retrieved from: www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/netzpolitik/fdp-sieg-bei-buergerrechten-stoppschild-fuer-zensursula-a-655565.html

18 Rötterkamp, Anne (2016): Internet Pornografie - Zahlen, Statistiken, Fakten. - Netzsieger, 05.01.2016. Retrieved from: www.netzsieger.de/ratgeber/internet-pornografie-statistiken

19 Pickert, Nils (2016): Nackte Tatsachen gegen Sexismus. - Zeit Online (20.04.2016). Retrieved from: www.zeit.de/gesellschaft/zeitgeschehen/2016-04/sexismus-pinkstinks-werbung-verbot/komplettansicht

All internet links were last accessed on 08.02.2018.

Selective Bibliography

Documents online

Recommendations

Lovelace, Linda ; MacGrady, Mike (1980): Ich packe aus. - München : Heyne (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.09.039).

Dworkin, Andrea (1987): Pornographie. Männer beherrschen Frauen. - Köln : EMMA-Frauen-Verlag (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.09.014-1987).

Dines, Gail (2014): Pornland : wie die Pornoindustrie uns unserer Sexualität beraubt. - Mainz : Thiele (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.09.060-2).

FMT Press Documentation

Press Documentation on Pornography: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Selected FMT-Sources (lists)

FMT literature selection Pornography: PDF-Download

EMMA article Pornography: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Fighting Sexual Violence and (Marital) Rape

Fighting Sexual Violence and (Marital) Rape

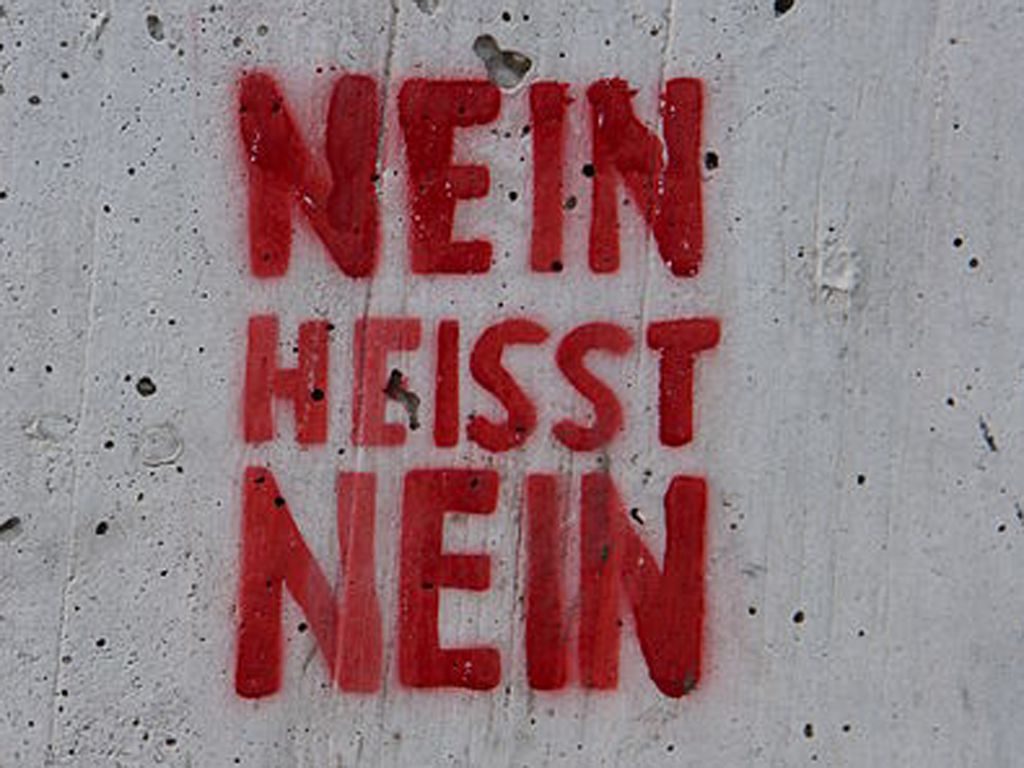

In the mid-1970s, the women’s movement brought the epidemic of sexual violence to the public’s attention. The women fought for a sex crime law reform, that finally came through 1997 and 2016. In Germany today the principle rules: No means No. › mehr

Motherhood and the Feminine in Patriarchy

Motherhood and the Feminine in Patriarchy

The women’s movement critisized the hypocrisy of patriarchal society with respect to motherhood: in Germany mothers were glorified, but left alone with their workload. Feminists also questioned the dogma that women had to become mothers to be fulfilled. › mehr

Sexual Harassment - the Long Way to Sex Crime Legislation

Sexual Harassment - the Long Way to Sex Crime Legislation

Sexual harassment in the workplace became a public issue in Germany in the late 1970s, studies and debates have followed until it finally became a part of the sex crime legislation. › mehr