One of the central issues of the Women’s Liberation Movement was the slackening of the automatic link between womanhood and motherhood. The dogma that a woman is only then complete when she has become a mother was questioned. The women’s movement uncovered the hypocrisy of patriarchal society with respect to motherhood: on the one hand, mothers were glorified, yet left stranded with all domestic and educational duties on the other.

The (secret) disregard for mothers was reflected in many women’s groups: non-mothers cut themselves off from the omnipresent ‘Mutterschaftszwang’ or ‘motherhood compulsion’, and mothers were underrepresented in these groups due to a lack of time and child care. From the mid-1970s politics, science, and the media reacted to women’s rebellion against the Mutterschaftszwang with the promotion of so-called “new femininity” or “new motherliness”. But the propagation of a “natural femininity” by no means only emerged from the conservative camp, but also from within the women’s movement itself. The idea of women as sentimental “natural beings” was in fashion again. The conflict between difference feminists and anti-biologists began – and still continues today.

January 1968: Kinderladen-Movement

On the initiative of the former film student Helke Sander, approximately 100 women and some men from the student movement come together in Berlin to establish the first “Kinderläden” [“child shops”]. Child care is the woman’s responsibility, even within the left-wing student milieu. The students want — with the help of the so-called Kinderläden, self-organised kindergartens that are often set up in empty storefronts — to be able to study and to take part in the student movement’s evening meetings.1

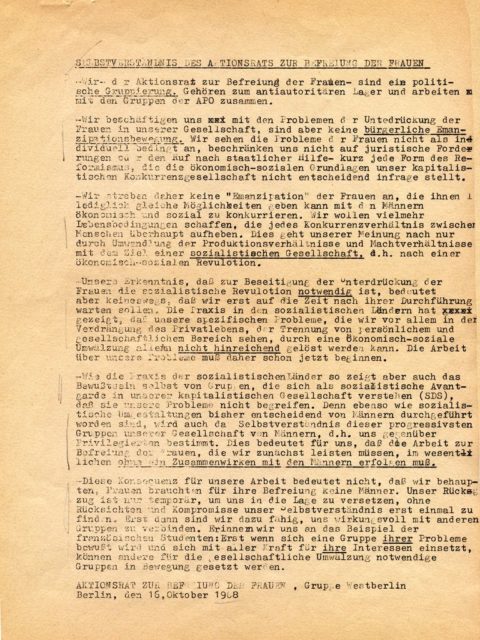

In addition to practical self-help, however, a debate about the division of labour between men and women — increasingly called into question by mothers — evolves out of the Kinderladen-movement. Shortly after the first Kinderladen-meeting, some of the participants establish the Aktionsrat zur Befreiung der Frauen2. Soon hundreds of Kinderläden are established, and not just in Berlin.

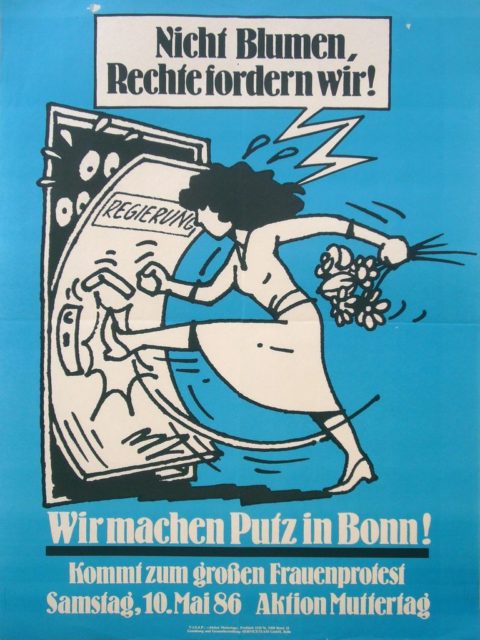

14 May 1972: Protests against Mother’s Day

Women’s groups from across the country organise protests against Mother’s Day. Motto: “Mother’s Day — a holiday? What are we actually celebrating? Our underpayment? Our unpaid housework? Our illegal abortions?“3

12 March 1975: New Femininity Movement

Karin Struck’s book Die Mutter4 is published. The author — whose debut novel Klassenliebe5 was published two years previously and is considered a literary sensation — now publishes a plea for “motherly, warming femininity” and a “new, feminine perception of reality“.6 Struck’s protagonist Nora Hanfland, a mother of two children, sets out to find the meaning of motherhood and birth and ultimately demands “[…] that we fight for the veneration of mothers, of children, of large families, that we take up the cause of motherhood“.7

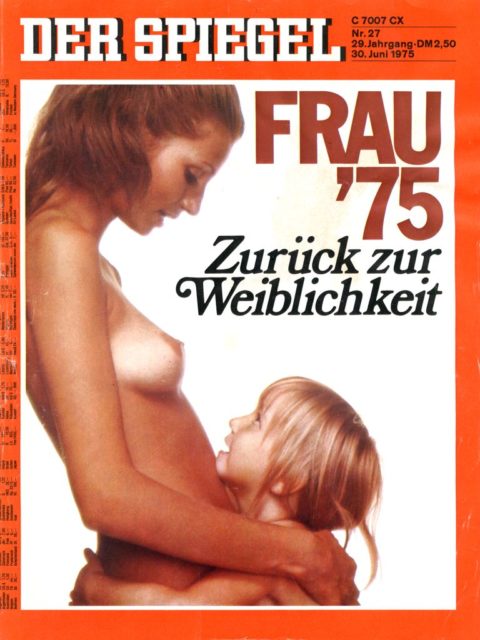

With this book, Struck becomes one of the main proponents of “new femininity”, a movement that — in contrast to the anti-biologists — insists on ‘natural differences’ between the genders. A couple of weeks later, the Spiegel comments on Struck’s book in the headline story Zurück zur Weiblichkeit thus: “Three years ago a novel like ‘Die Mutter’ by Karin Struck — which deals with the yearning to be ‘fertile like a field’ and which lauds pregnancies as stations on the way to freedom, to the ‘great erotic mother’ — would have been barely conceivable”8

30 June 1975: Biologistic Backlash

In his essay Der anatomische Imperativ, Wilhelm Bittorf insists that biological gender difference more strongly shapes — even defines — women and men than feminists claim. Thus, only a couple of years after the emergence of the women’s movement, the backlash arrives in earnest. But even within the women’s movement itself, those voices that insist on ‘natural differences’ between women and men grow louder. For example, it is claimed that women and especially mothers are naturally more peaceful than men. Consequently, it is not a question of negating gender difference, but of valuing more than ever before the particular ‘feminine qualities’ of woman. Women are not the ‘same’ but ‘equal’. This is the same trend that mounts the demand for “wages for housework” (for more see our text on women who work).

April 1976:

An interview with Simone de Beauvoir by Alice Schwarzer is published in the Spiegel that addresses the phenomenon of “new femininity” within the women’s movement. During this conversation, Beauvoir warns against attributing certain qualities to women by virtue of their ‘nature’ and implying that “woman has an especial bond to the earth, has the rhythm of the moon and the tides in her blood, and all that stuff […] That she has more soul, is by nature less destructive et cetera. No! There’s something to this, but it’s not our nature, but the result of our living conditions.”9 And she further explains: “If you tell us: ‘Always stay feminine. Let us do all the annoying things: power, honour, career […] Be happy with the way that you are: earth-bound, concerned with care work…’ If we are told this, we should be on our guard! […] Women who believe this revert to the irrational, the mystical, the cosmical. They play men’s game – because in this way, they will be better suppressed, better kept away from knowledge and power. The eternal feminine is a lie because nature plays a very minor role in human development, we are social beings. Furthermore, since I do not think that woman is by nature inferior to man, I also do not think that she is inherently superior to him.“10

Beauvoir and Schwarzer are among the most significant representatives of anti-biological equality feminism. So-called difference feminism, on the other hand, assumes biologically-given and formative differences between the sexes beyond the ability to give birth. The central issue for difference feminists is that so-called ‘feminine’ qualities are viewed as less valuable than ‘masculine’ ones in the patriarchy. They therefore call for the revolutionisation of the patriarchy’s “symbolic order” in order to raise the status of these so-called ‘feminine values’.11 The most important proponents of this movement are the French psychoanalyst and cultural theorist Lucy Irigaray and the French writer Hélène Cixous.

1977:

Feministinnen und Kinder12 by Eva-Maria Stark is published with Frauenoffensive in Frauenjahrbuch 197713. The text, in which Stark summarises her book Gebären und geboren werden – Eine Streitschrift für die Neugestaltung von Schwangerschaft, Geburt und Mutterschaft14 is widely received and discussed.15 Stark postulates: “Mothers’ affection and sacrifice receive substantial social reinforcement, but it is a relationship deeply rooted in the physical and psychological systems of mother and child, and not extant anywhere else, nor comparable to anything else.“16 Anti-biologist feminists criticise the suppression of the father-child relationship, which relieves fathers of responsibility for child care.

July 1979:

Maternity leave law comes into force on July 1.17 The law extends the mother’s paid leave after the birth of a child from eight weeks to six months. Feminists criticise the law as “cementing Stone Age maxims: Daddy feeds the family – Mummy belongs with the child”18 They warn of the risk to professional women of a long absence from work and call for “parental leave”, so that fathers are also reminded of their duties in matters of child care. – Parental leave – so-called “Elternzeit”, including “Vätermonate” [father’s months] – should have become law in 2007. At least, theoretically.

1979

The peace movement is launched with NATO’s so-called “double track” decision. Over the following years, hundreds of thousands of people take part in demonstrations against the arms race and the Cold War. Within the peace movement, some active women form a separate fraction in the name of “woman’s natural peaceableness”. For example, citing alleged feminine peaceableness, the feminist magazine Courage calls for women to “fight so that women alone are entitled to make the decisions about war and peace”.19 EMMA criticises this attitude as biologistic: “Although the fight for peace is more than justified and necessary, to conduct it in the name of ‘woman’s natural peaceableness’ and of ‘women’s special relationship to life’ is not only naïve and stupid, but frankly reactionary. This is because: 1) Women are not ‘naturally’ more peaceable, but at best more humane due to their conditioning and circumstances in life, and at worst only good because they simply do not have the power to be bad. 2) Is the peace question anything more than a question of power?”20

![Mütter an die Macht : die neue Frauen-Bewegung (1989). - Pass-Weingartz, Dorothee [Hrsg.] ; Erler, Gisela [Hrsg.]. Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.015) Mütter an die Macht : die neue Frauen-Bewegung (1989). - Pass-Weingartz, Dorothee [Hrsg.] ; Erler, Gisela [Hrsg.]. Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.015)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Erler_Muetter_an_die_Macht-480x640.jpg)

June 1981:

The CDU politician Norbert Blüm champions the catch phrase “the soft power of the family”. Blüm – then head of the Christlich-Soziale Arbeitnehmerschaft (CDA) and soon thereafter the Employment and Social Services Minister under Chancellor Kohl – presents a policy paper in which he demands: “The status of the mother must be raised.” Blum states that the “biological inequalities between man and women” correspond to “different ways of behaving”. And “The work of mothering is self-fulfilling for women.”“23 Blüm even manages to antagonise women in his own party with his theories. EMMA makes Blüm the Pasha of the Month. Furthermore, the CDU comes up with the term “Wahlfreiheit”, “freedom of choice”, to describe the woman’s choice between work and family.24

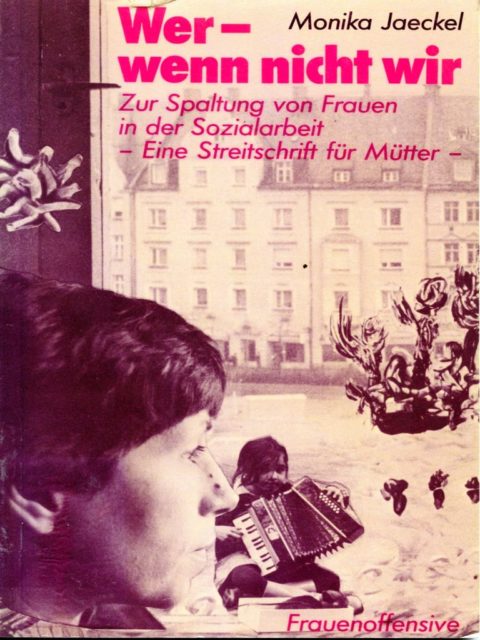

1981

Streitschrift für Mütter25 by Monika Jaeckel is published with Frauenoffensive. In this book, the sociologist and childless women’s rights activist criticises the women’s movement’s hostility towards mothers. Instead of labelling mothers as “strike breakers”, Jaeckel demands: “It’s time to say, to experience, and to accept what mothers feel. It’s time to accept them and to support them in their pride, which belongs to all women.”26 In 1987, Jaeckel becomes one of the first signatories of the so-called Müttermanifest, which calls for the valorisation of work in the home and for the family.

22/23 November 1986

Das Müttermanifest27 which will be published in 1987, emerges from the congress Leben mit Kindern – Mütter werden laut in Bonn, which is supported financially and in practice by the Green Party and attended by approximately 500 women. The manifest postulates: “Ultimately it’s about developing a picture of emancipation in which the contents of traditional women’s work – i.e. taking care of people, the perception of social relations, the questioning of so-called ‘practical constraints’ – are integrated as legitimate values and recognised accordingly as social, political, financial.”28 The demands of the manifest include “sufficient and independent financial security for the care work that we do”, i.e. a housewife’s wage. The women no longer want to be at the mercy of men’s “snail’s pace” with respect to participation in family work, but instead want to create their own structures like mother’s centres.29 Among the 22 initial signatories are Monika Jaeckel, the Member of Parliament for the Green Party Christa Nickels, and the sociologist Gisela Erler, who will publish the polemic Mütter an die Macht30 in 1987.

![„Leben mit Kindern - Mütter werden laut“ : Dokumentation des Kongresses vom 22./23.11.86 : Gedanken zur Mütterpolitik (1987). - Die Grünen [Hrsg.], Selbstverlag (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.065). „Leben mit Kindern - Mütter werden laut“ : Dokumentation des Kongresses vom 22./23.11.86 : Gedanken zur Mütterpolitik (1987). - Die Grünen [Hrsg.], Selbstverlag (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.065).](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Leben_mit_Kindern_Muetter_werden_laut-480x640.jpg)

Das Müttermanifest is hotly debated in the media and within the women’s movement.31 Within the Green Party, the manifesto is similarly met with criticism. A Stellungnahme grüner Frauen zum Müttermanifest signed by the Members of Parliament Marieluise Beck and Verena Krieger as well as the Landesarbeitsgemeinschaft Frauen der Grünen in Niedersachen states: “We regret that mothers’ legitimate concerns are married in the Müttermanifest to an image of women that we have been fighting against for years.”32

What happens next?

The following years and even decades are characterised by a struggle for better social conditions for mothers (as well as fathers) and children, the goal being that women no longer have to choose between „Kind oder Karriere“, “child or career”. However, the fatal term “Wahlfreiheit” – previously coined by the conservatives – is taken up by the SPD as well as the other political parties. At the same time, laws that protect mothers and housewives are systematically dismantled in the name of “equal rights”.

In no other western country is the proportion of mothers working part-time – at approximately 40% – currently so high as in Germany (see the 2017 OECD study about partnership in family and work 2017). Experts and feminists predict a high level of old-age poverty for this seemingly emancipated generation of women, who followed the lure of the aforementioned “freedom of choice” by giving up work for child care or only working part-time. It is a time of upheaval and contradiction, of both progress and regress.

References

1 Sander, Helke (1973): Rede vor dem Aktionsrat zur Befreiung der Frauen, siehe Pressedokumentation: Chronik der Neuen Frauenbewegung, 1968-1970. (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-FE.03.01-1968-1970, Kapitel 3, 1)

2 Selbstverständnis des Aktionsrats zur Befreiung der Frauen (16.10.1968): Aktionsrat zur Befreiung der Frauen [Hrsg.], see pamphlet in FMT Image Archive (FMT Image ID: FB.04.161) and Selbstverständnis des Aktionsrats zur Befreiung der Frauen (16.10.1968). - Aktionsrat zur Befreiung der Frauen [Hrsg.], see Pressedokumentation: Chronik der Neuen Frauenbewegung, 1968-1970 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-FE.03.01-1968-1970, Kapitel 3.2, 4).

3 Muttertag - Ein Feiertag? (1972). - Frauenaktion 70 [Hrsg.] ; DKP-Frauenarbeitskreis [Hrsg.] ; Weiberrat [Hrsg.], see pamphlet in FMT Image Archive (FMT Image ID: FB.07.047).

4 Struck, Karin (1978): Die Mutter : Roman. - Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp.

5 Struck, Karin (1973): Klassenliebe : Roman. - Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

6 Monika Sperr (1978): Karin Struck - wozu sie benutzt wird und was sie dazu beiträgt. - In: EMMA, Nr. 3, p. 45. Retrieved from: http://www.emma.de/lesesaal/45146#pages/45

7 Peter Handke über Karin Struck: „Die Mutter“ Denunziation ohne Wahrnehmung (1975). - In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 12, p. 147. Retrieved from: http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-41599913.html

8 Frau '75: "Grosse Erotische Mutter" (1975). - In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 27, p. 31. Retrieved from: http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-41496347.html

9 Schwarzer, Alice (1976): Das Ewig Weibliche ist eine Lüge. - In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 15, p. 201. Retrieved from: http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-41279965.html

10 Ibid..

11 Metzler-Lexikon Gender Studies, Geschlechterforschung : Ansätze - Personen - Grundbegriffe (2002). - Kroll, Renate [Hrsg.]. Stuttgart : Metzler, p. 50f., S. 68f. , p. 191f. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.12.NA.002).

12 Stark, Eva-Maria (1977): Feministinnen und Kinder. - In: Frauenjahrbuch '77. - Stahmer, Anne [Hrsg.] ; Pulz, Traudi [Hrsg.] ; Jaeckel, Monika [Hrsg.] ; Reinig, Christa [Hrsg.] ; Kahn-Ackermann, Susanne [Hrsg.] ; Kowitzke, Gerlinde [Hrsg.]. München : Frauenoffensive, pp. 54 - 60. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.001-1977)

13 Frauenjahrbuch '77. - Stahmer, Anne [Hrsg.] ; Pulz, Traudi [Hrsg.] ; Jaeckel, Monika [Hrsg.] ; Reinig, Christa [Hrsg.] ; Kahn-Ackermann, Susanne [Hrsg.] ; Kowitzke, Gerlinde [Hrsg.]. München : Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.001-1977)

14 Stark, Eva-Maria (1981): Geboren werden und gebären : eine Streitschrift für die Neugestaltung von Schwangerschaft, Geburt und Mutterschaft. - München : Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.013)

15 Wetterer, Angelika (1983): Die neue Mütterlichkeit : Über Brüste, Lüste und andere Stil(l)blüten aus der Frauenbewegung. - In: Bauchlandungen : Abtreibung, Sexualität, Kinderwunsch. - Häußler, Monika [Hrsg.] ; Helfferich, Cornelia [Hrsg.] ; Walterspiel, Gabriela [Hrsg.] ; Wetterer, Angelika [Hrsg.]. München : Frauenbuchverlag Weismann, pp. 117-134. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.11.033-a)

16 Stark, Eva-Maria (1977): Feministinnen und Kinder. - In: Frauenjahrbuch '77. - Stahmer, Anne [Hrsg.] ; Pulz, Traudi [Hrsg.] ; Jaeckel, Monika [Hrsg.] ; Reinig, Christa [Hrsg.] ; Kahn-Ackermann, Susanne [Hrsg.] ; Kowitzke, Gerlinde [Hrsg.]. München : Frauenoffensive, p. 55. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.001-1977)

17 Kischke, Martina I. (1979): Wo sind denn nun eigentlich die Väter geblieben?. - In: Frankfurter Rundschau, 07.04.1979, see Pressedokumentation: Chronologie der Neuen Frauenbewegung, 1979. (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-FE.03.01-1979, Kapitel 3, 4)

18 Pinl, Claudia (1978): Gefährlicher Mutterschutz. - In: EMMA, Nr, 9, p. 29. Retrieved from: http://www.emma.de/lesesaal/45152#pages/31

19 Schwarzer, Alice (1981): So fing es an! : 10 Jahre Frauenbewegung. - Köln : EMMA-Frauen-Verlag, p. 114. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.164-1981)

20 Ibid., p.114.

21 Ibid., p. 109ff..

22 Ibid., p. 109.

23 Die neue Zeit kommt im Gewand der Mütterlichkeit : Das Grundsatzpapier der Sozialausschüsse (CDA) für die nächste Bundestagung, die unter dem Motto „Familie - Freiheit - Zukunft“ steht : Leitsätze : Die sanfte Gewalt der Familie (1981). - In: Frankfurter Rundschau, 04.08.1981, see Pressedokumentation: Feministische Debatten und Ereignisse, 1981. (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-FE.03.02-1981, Kapitel 3.1, 6)

24 Schwarzer, Alice (1981): So fing es an! : 10 Jahre Frauenbewegung. - Köln : EMMA-Frauen-Verlag, p. 111. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.164-1981)

25 Jaeckel, Monika: Wer - wenn nicht wir : zur Spaltung von Frauen in d. Sozialarbeit : eine Streitschrift für Mütter (1981). - München : Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.006)

26 Ibid., p. 6.

27 „Leben mit Kindern - Mütter werden laut“ : Dokumentation des Kongresses vom 22./23.11.86 : Gedanken zur Mütterpolitik (1987). - Die Grünen [Hrsg.], Selbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.065)

28 Ibid., p. 6.

29 Ibid., p. 7.

30 Mütter an die Macht : die neue Frauen-Bewegung (1989). - Pass-Weingartz, Dorothee [Hrsg.] ; Erler, Gisela [Hrsg.]. Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.015)

31 See Pressedokumentation: Mütter II: "Müttermanifest" aus dem Umfeld Grüner Frauen, 1986-1988. (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-LE.05.02)

32 Wo liegt der Frauen Glück? : Neue Wege zwischen Beruf und Kindern (1988). - Beck-Oberdorf, Marieluise [Hrsg.] ; Bussfeld, Barbara [Hrsg.] ; Meiners, Birgit [Hrsg.]. Köln : Kölner Volksblatt-Verlag, p. 128. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.045)

Date of the last linkcheck: 29.01.2018.

Selective Bibliography

Documents online

Bittorf, Wilhelm: Der anatomische Imperativ. - In: Der Spiegel, 30.06.1975, p. 42 - 43.

Rabenmütter von A - Z (1983). - Courage, Sonderheft, Nr. 9

Späte Mütter - Das Tabu (2013). - In: EMMA, Nr. 4, p. 20 - 30.

OECD-Studie zu Partnerschaftlichkeit in Familie und Beruf (2017)

Recommendations

Frauen und Mütter (1979): Beiträge zur 3. Sommeruniversität von und für Frauen, 1978. - Berlin : Selbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.009-03)

Wetterer, Angelika (1983): Die neue Mütterlichkeit : Über Brüste, Lüste und andere Stil(l)blüten aus der Frauenbewegung. - In: Bauchlandungen. - Wetterer, Angelika [Hrsg.]. München : Frauenbuchverlag Weismann, S. 117-134. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.11.033-a)

Nicht nur Blumen - Rechte fordern wir! : Dokumentation der Frauen-Demonstration am 12. Mai 1984 in Bonn anlässlich des Muttertages (1984). - Arndt, Tina [Hrsg.] ; Baumann, Heidi [Hrsg.] u.a.. Bonn : Leppelt. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.099)

Badinter, Elisabeth (1985): Die Mutterliebe : Geschichte eines Gefühls vom 17. Jahrhundert bis heute. - München : Dt. Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.001)

Mütter im Zentrum - Mütterzentrum : Wo Frauen mit ihren Kindern leben (1985). - Deuschle, Dorle [Hrsg.]. München : Goldmann. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.035)

Neue Mütterlichkeit : Ortsbestimmungen (1986). - Pasero, Ursula [Hrsg.] ; Pfäfflin, Ursula [Hrsg.]. Gütersloh : Gütersloher Verlagshaus Mohn. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.025)

Scheich, Elvira (1986): Frauenpolitik nach Tschernobyl. - In: Beiträge zur feministischen Theorie und Praxis, Nr. 18, S. 21 - 30. (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-F014:1986-18-a)

"Leben mit Kindern - Mütter werden laut" : Dokumentation des Kongresses vom 22./23.11.86 : Gedanken zur Mütterpolitik (1987). - Die Grünen [Hrsg.]. Bonn : Selbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.065)

Mütter an die Macht : Die neue Frauen-Bewegung (1989). - Pass-Weingartz, Dorothee [Hrsg.] ; Erler, Gisela [Hrsg.]. Reinbek : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.015)

Chamberlayne, Prue (1990): The mothers' manifesto and disputes over 'Mütterlichkeit'. - In: Feminist Review : Selbstverlag.(FMT Shelf Mark: Le.05.a)

Hrdy, Sarah Blaffer (2000): Mutter Natur : die weibliche Seite der Evolution. - Berlin : Berlin-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.009)

Diehl, Sarah (2010): Die Uhr, die nicht tickt : eine Streitschrift. - Zürich : Arche. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.055)

Donath, Orna (2016): # _regretting motherhood : wenn Mütter bereuen. - München : Knaus. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.079)

FMT Press Documentation

Press Dokumentation on Motherhood and Womanhood in Patriarchy: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Selected FMT-Sources (lists)

Selected literature Motherhood and Womanhood in Patriarchy: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Women Who Work: Housework and Claim for Equal Pay

Women Who Work: Housework and Claim for Equal Pay

When the women’s movement started, housework was still by law a woman’s job. Feminists fought successfully for the abolition of this law. › mehr

Women's Health and Patriarchal Medicine

Women's Health and Patriarchal Medicine

Self-determination and knowledge of one’s own body – women’s health initiatives were directed against a patronizing and patriarchal medicine that made the male body the point of reference while the female body was both medicalised and pathologised. › mehr

Law, Ruling and 'Male Justice'

Law, Ruling and 'Male Justice'

As the women’s movement got under way, law was almost exclusively administered by men. Feminists analyse that there is a “male justice” › mehr

![© Franziska Becker „Leben mit Kindern - Mütter werden laut“ : Dokumentation des Kongresses vom 22./23.11.86 : Gedanken zur Mütterpolitik (1987). - Die Grünen [Hrsg.], Selbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.065) © Franziska Becker „Leben mit Kindern - Mütter werden laut“ : Dokumentation des Kongresses vom 22./23.11.86 : Gedanken zur Mütterpolitik (1987). - Die Grünen [Hrsg.], Selbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.05.065)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Cartoon_Franziska_Becker-640x640.jpg)