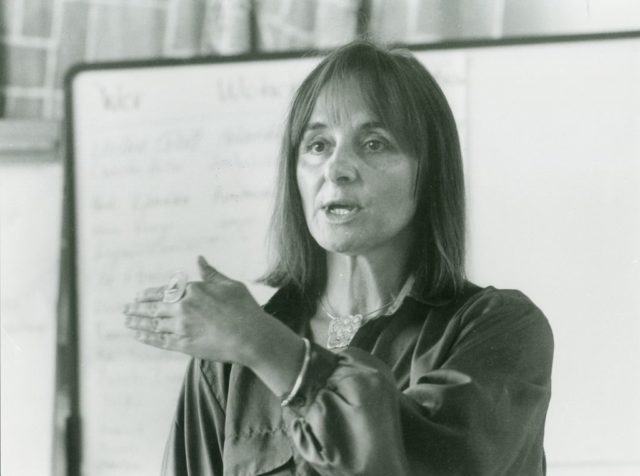

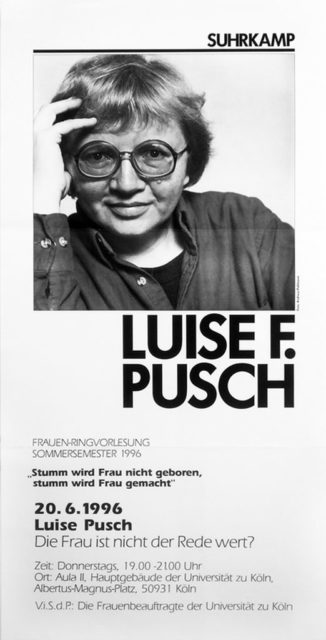

From the mid-1970s, feminists began to denounce the subordination, or rather the absence, of women in speech and writing and called for a gender-neutral language. Trailblazers like the linguists Senta Trömel-Plötz and Luise Pusch analysed the male-dominated (German) language with scientific methods and thus established feministische Linguistik [‘feminist linguistics’] in Germany. The struggle for a female presence in speech and writing became a project for the women’s movement, which wanted to see the growing participation of women in society reflected in language. At the same time, gendered language behaviour and non-verbal communication became the focus of feminist thought.

1974/75: ‚man‚ or ‚frau‚?

The creators of the legendary Frauenkalender1 – published for the first time in the autumn of 1974 (and printed until 2000) – are the first to introduce the much-discussed pronoun “frau” (as a feminist alternative to the indefinite pronoun ‘man’ or ‘one’, homophone of the personal noun ‘Mann’ or ‘man’). They mean it half seriously, half ironically. From then on, the provocative indefinite pronoun ‘frau’ enters common usage (see our text on feminist projects in Germany).

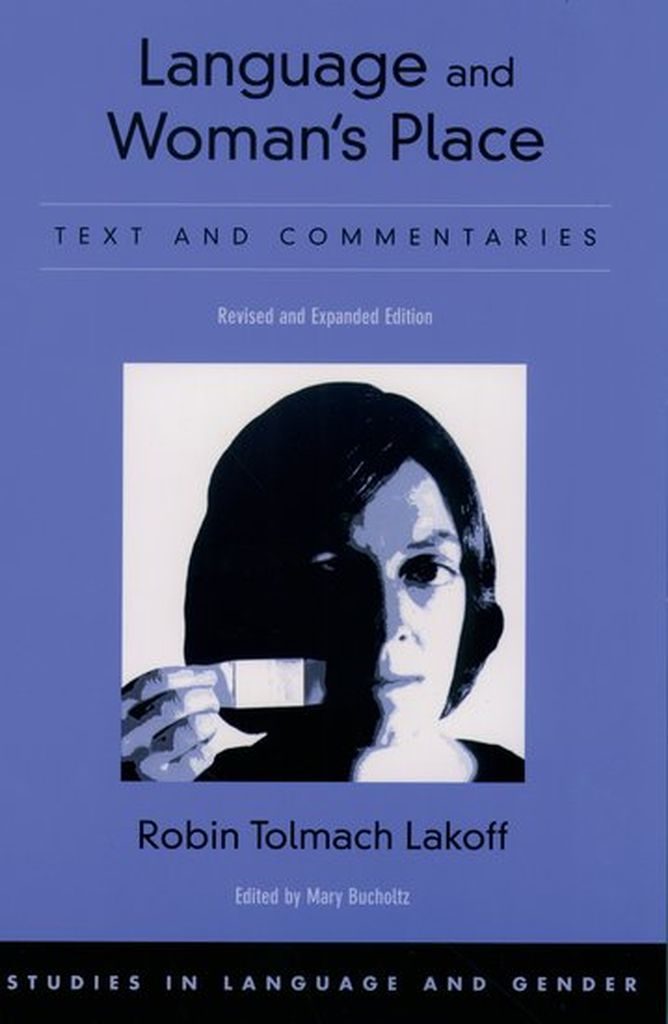

The Americans Mary Ritchie Key (1972)2 and Robin Lakoff (1973)3 are the first to publish linguistic theories on ‘female language’. At the University of Trier, the linguist Ingrid Guentherodt holds the first seminar in Germany on the Rollenverhalten der Frau und Sprache, women’s role-specific behaviour and language, in the winter semester of 1974/755. Guentheordt will develop gender-neutral policies for legal administrative language5 in 1983.

April 1977: A Conference On Female Language

A conference about female language takes place in New York, at which with 35 papers are given. Theresia Sauter-Bailliet covers the conference for the magazine Courage and summarises: “The conference as a whole has shown me how important it is for female self-image and for the recovery of women’s history to trace this female-specific way of experiencing and communicating.”

Autumn 1978: Language = An Instrument Of Domination

With Linguistik und Frauensprache6 Senta Trömel-Plötz – who had studied linguistics in the USA – introduces Key and Lakoff’s theories to the German public. As professor at the University of Konstanz, Trömel-Plötz analyses the German language as a ‘men’s language’ and an ‘instrument of domination’. This is because women’s social subordination finds its equivalent in language.

![Gibt es eine Frauensprache? / Theresia Sauter-Bailliet. - [Electronic ed.]. In: Courage : Berliner Frauenzeitung. - 2(1977), H. 10, S. 37 - 38 Gibt es eine Frauensprache? / Theresia Sauter-Bailliet. - [Electronic ed.]. In: Courage : Berliner Frauenzeitung. - 2(1977), H. 10, S. 37 - 38](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Cover_Courage_1977_10-480x640.jpg)

1980: Sexist Language

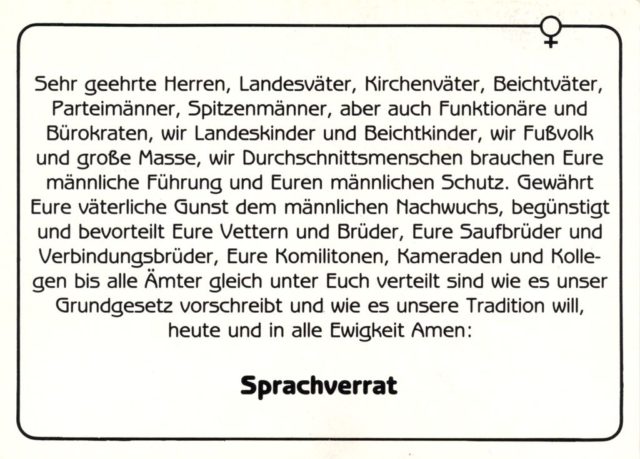

Following the American model, in 1980 (and again in 1981) Senta Trömel-Plötz, Ingrid Guentherodt, Marlis Hellinger, and Luise F. Pusch publish Richtlinien zur Vermeidung sexistischen Sprachgebrauchs9 in Linguistische Berichte.

Sexist language is defined in these linguistic guidelines as follows: “Language is sexist when it ignores women and their accomplishments, when it describes women exclusively as dependent and subordinate to men, when it depicts women solely in stereotypical roles and denies them interests and capabilities beyond these, and when women are humiliated and ridiculed in condescending speech.“10

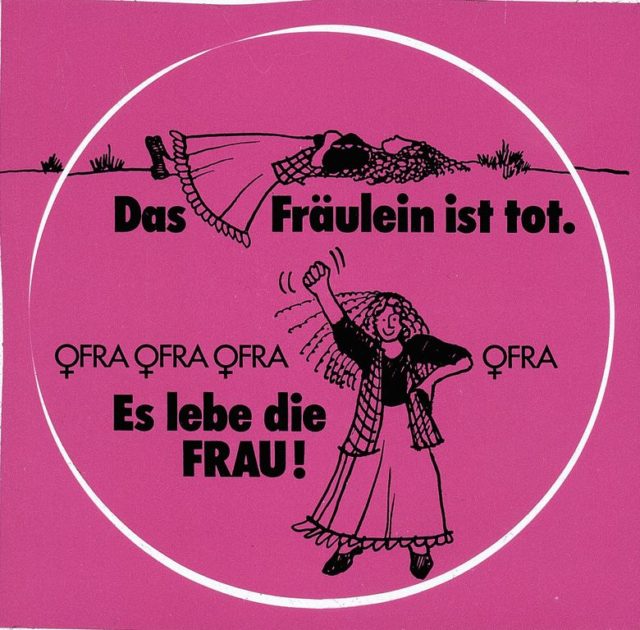

22 December 1982: Bye, Bye „Miss“

Frankfurt’s industrial tribunal sides with a female employee who had gone to court to contest the use of “Fräulein” or “Miss” in a reference.

The tribunal determines that the choice of address indicates a “transformed self-image that rejects the assignment of different social positions to women and men, to unmarried and single women.“11

As early as 1972, a decree by the ministry of the interior had already put an end to the decades-long controversy over the form of address for unmarried women in official language. By contrast, the public debate continues into the early 1990s.12

December 1983: The Beginning Of the Binnen-I

The Swiss weekly newspaper WOZ introduces the so-called Binnen-I, which aims to make women – who were hitherto only ‘implied’ in the male form – linguistically visible without the need to use both the male and the female form: i.e., instead of Leser (generic masculine) or Leserinnen und Leser (both feminine and masculine), the combined form LeserInnen. A few years later, and after violent internal debate, the taz formally decides to use the Binnen-I.13 EMMA uses the Binnen-I from 1987. The Duden dictionary to this day does not recognise the Binnen-I, despite controversial discussion, and states: “The use of a capitalised I inside of a word (Binnen-I) does not comply with German spelling rules.“14

1984: Language And (Male) Power

Das Deutsche als Männersprache15, by Luise Pusch is published. This is Pusch’s first essay collection of many on the subject of linguistic criticism. It contains a text from 1983 entitled Das Duden-Bedeutungswörterbuch als Trivialroman16, in which Pusch elaborates on the gender stereotypes in the dictionary’s examples sentences and confirms that the Duden editors demonstrate an “abysmal contempt for women”.17 Das Deutsche als Männersprache is, with 140,000 copies, currently the bestselling work about linguistics in German post-war history.

![Gewalt durch Sprache : die Vergewaltigung von Frauen in Gesprächen (1984). - Trömel-Plötz, Senta [Hrsg.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Signatur: KU.23.010) Gewalt durch Sprache : die Vergewaltigung von Frauen in Gesprächen (1984). - Trömel-Plötz, Senta [Hrsg.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Signatur: KU.23.010)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Troemel-Ploetz_Gewalt_durch_Sprache-407x640.jpg)

11. September 1985: It Gets Serious

On the initiative of the Member of State Parliament Marita Haibach (Green Party)20 and backed by the Deutscher Juristinnenbund, the first hearing on the equal treatment of women and men in the language of legal texts takes place at the state parliament in Hessen.21 Other states and finally also the Bundestag follow Hessen’s example.

November 1985: Sexism And Language

The International Women’s Alliance, a UN association with more than 70 member organisations worldwide, meets in Berlin to discuss Sexismus und Sprache, sexism and language.22

6 November 1987: Parliament Debates About Gender Neutral Designations

There is a parliamentary debate on the request tabled by all parties to introduce “gender neutral designations, formulations in law, legislation, and administrative regulations“. On 20th November the Zeit prints the speech of the „most trenchant speaker“,the Minister for Women Rita Süssmuth (CDU). Süssmuth characterises the debate as “highly irritating” due the fact that it is long overdue.23

![Das Gelächter der Geschlechter : Humor u. Macht in Gesprächen von Frauen und Männern (1996). - Helga Kotthoff [Hrsg.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Signatur: KU.23.028; versch. Auflagen vorhanden) Das Gelächter der Geschlechter : Humor u. Macht in Gesprächen von Frauen und Männern (1996). - Helga Kotthoff [Hrsg.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Signatur: KU.23.028; versch. Auflagen vorhanden)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Kotthoff_Das_Gelaechter_der_Geschlechter-418x640.jpg)

1988: Das Gelächter der Geschlechter

Das Gelächter der Geschlechter24 edited by the linguist Helga Kotthoff analyses how men and women use humour to consolidate the balance of power (men) or to rebel against it (women).

Beginning Of The 1990s

After German reunification, there is a degree of tension between West German feminists and East German women’s rights activists. One of the chief differences is the Western German critique of gendered language. Many East German women consider the inclusion of female forms in speech and writing – or even the Binnen-I – to be “ridiculous”. They wonder if West German women have nothing else to worry about than this debate about gender-neutral language.25 To a large extent, this East/West divide still exists today in feminist linguistic criticism.

11 May 1990: Time’s Up For The Generic Masculine

On the recommendation of the Legal Affairs Committee, the Bundestag agrees to avoid using the generic masculine in legal language, the aim being to no longer exclude women in speech and writing. The generic masculine is to be replaced with alternate forms. However, the gender-neutral form with the capitalised Binnen-I is rejected by parliament, as it “does not correspond to the accepted rules of the German language” and its usage results in “formulations that are difficult to understand“.26

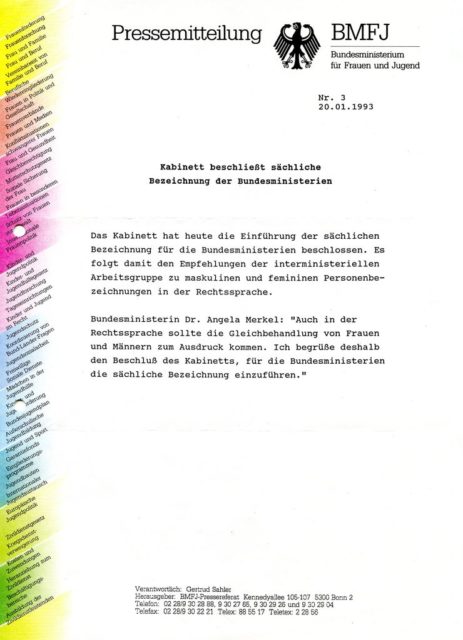

1993: Further Steps On The Way To Gender-Neutral Language

On January 20, the German government votes in favour of describing federal ministeries in gender-neutral language. Angela Merkel, the Federal Minister for Women and Youth, welcomes this step towards implementing equality in legal language in a press release.27

On behalf of the German commission for UNESCO, the professors of linguistics Marlies Hellinger and Christine Bierbach formulate the Richtlinien für einen nicht-sexistischen Sprachgebrauch28. These guidelines are addressed to all “who use the German language professionally, both within and outside of UNESCO institutions, whether at school, at university, in parliament, in the media, or the civil service. They are aimed at authors of learning and teaching materials, of specialist texts, of radio and television texts, of dictionaries, of encyclopaedias, of speeches and lectures, and of magazine articles of any kind”.“29

1995: No Professorships For Feminist Linguistics

In her Einführung in die feministische Sprachwissenschaft30 the linguist Ingrid Samel complains that there isn’t a single professorial chair for this area of research, despite the fact that the subject is discussed widely outside of university research.31 Even the two pioneers of feminist linguistics Senta Trömel-Plötz and Luise F. Pusch are denied permanent professorships.32

What happens next?

In 2004, Senta Trömel-Plötz concludes that “in Germany, the need for linguistic equality must no longer be discussed today.33 The naming of both genders is widely accepted as normal by the public: politicians generally use the so-called “Splitting-Methode” (e.g., “Bürgerinnen und Bürger”), and this form has also prevailed in the language of the news. Local authority equality laws also by now prescribe gender-neutral formulations (e.g., Studierende) or the naming of both genders.

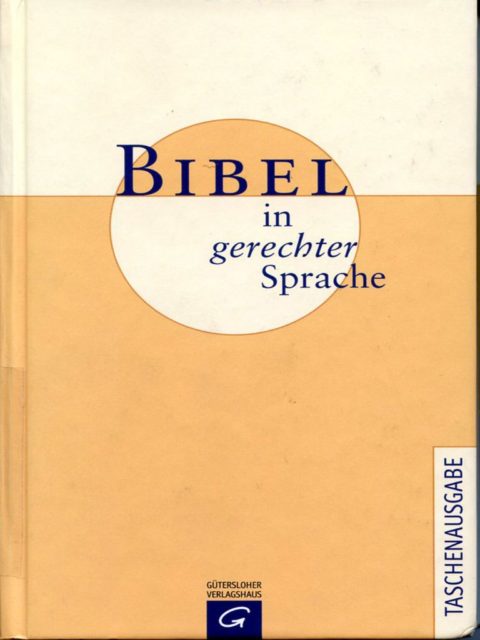

The result of a new translation of the Bible is published in 2006 as the Bibel in gerechter Sprache34 (more about it in our text on religion & church). The projects is initiated by an “editorial board” consisting of 13 theologians.

Approximately 50 theologians retranslate the Old and the New Testaments. The use of gender-neutral language is only one aspect of this new, non-discriminatory translation, albeit an important one: “In the Bibel in gerechter Sprache, passages that are not exclusively about men, but about both genders are consistently made visible. Thus, Apostelinnen [‘female apostles’], Diakoninnen [‘deaconesses’], Prophetinnen [‘female prophets’], and Pharisäerinnen [‘female Pharisees’] feature in the wording of the text. It becomes clear that women were actively involved in scriptural events […], that they are – then as now – addressed and not only implied”..“ (see press release).

In 2011, the generic feminine is introduced at the University of Leipzig in a revised version of the university’s Grundordnung [‘basic rules and regulations’] as an alternative to naming both genders with a forward slash. This means that all job titles are indicated in feminine form. Official university documents now contain references to “Professorinnen” (instead of “Professoren”), and a footnote clarifies that (male) professors are “implied”. In June 2013, SpiegelOnline publishes the article Sprachreform an der Uni Leipzig : Guten Tag, Herr Professorin, by Benjamin Haerdle, on which the media descend: they attack those responsible for the new regulations with streams of abuse, targeted misinformation, and unmitigated hate speeches. In particular, the director of the university Prof. Beate Schücking is the preferred target of the attacks.35

The so-called ‘queer movement’ calls for the “construct of the gender binary” to be questioned in language and introduces two new forms. 1) An underscore – Bürger_innen – symbolises the “gender gap”, i.e. the space between the male / female binary. 2) The “gender asterisk” – Bürger*innen or Frauen* – originally developed by the transgender movement aims to clarify the different forms of gender switching (e.g., transsexual, transgender, transvestite etc., in short: trans*). A controversial debate is held about these forms. Luise Pusch, for example, criticises the „gender gap“ as follows: „People who are cannot or do not want to identify as male or female are to feel represented by the underscore, women by the suffix. As a woman, I find it more than dissatisfactory to be reduced to a suffix after 30 years of engagement for fair language. It’s actually much worse than merely being implied.” EMMA also considers the entire discussion to be an overreaction and sticks with the Binnen-I.

As an alternative to the normative gender binary expressed in the most common salutations, Lann Hornscheidt – professor for gender studies at the Humboldt Universität in Berlin – proposes a neutral x-form (“Sehr geehrtx Professx”) on her homepage, preferring to be addressed in this manner herself. Hornscheidt’s suggestion attracts considerable media attention: a “shitstorm” ensues that encompasses threats of violence and a public call for the revocation of Hornscheidt’s professorship.36

A psychological study conducted by Dries Vervecken and Bettina Hannover at the Freie Universität, Berlin in 2015 shows that gender-neutral language influences children’s perception of professions.37 Almost 600 primary school children rated occupations differently attractive depending on whether they were read a gender-neutral or a male job description. The study demonstrates what feminist linguists have claimed since the 1970s: language creates our reality (see press release).

References

1 Frauenkalender '75 (1974). - Bookhagen, Renate [ed.] ; Schlaeger, Hilke [ed.] ; Scheu, Ursula [ed.] ; Schwarzer, Alice [ed.] ; Zurmühl, Sabine [ed.]. Berlin : Selbstverlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: NA.09.013-1975)

2 Key, Mary Ritchie (1972): Linguistic behaviour of male and female. - In: Linguistics, 88,pS. 15 - 31.

3 Lakoff, Robin (1973): The logic of politeness : or, minding your P's and Q's. - In: Papers from the Ninth Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society. Corum, Claudia et al. [ed.]. Chicago : Department of Linguistics, University of Chicago. p. 292 - 305.

4 Samel, Ingrid (1995): Einführung in die feministische Sprachwissenschaft. - Berlin : Schmidt, p. 10. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.NA.002

5 Guentherodt, Ingrid (1984): Androzentrische Sprache in deutschen Gesetzestexten und der Grundsatz der Gleichbehandlung von Männern und Frauen. - In: Muttersprache 94, p. 271 - 289. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23-a; Objektnr.: 3587)

6 Trömel-Plötz, Senta (1978): Linguistik und Frauensprache. - In: Linguistische Berichte 57, p. 49 - 68 und in: Frauen - Sprache - Literatur : fachwissenschaftliche Forschungsansätze und didaktische Modelle und Erfahrungsberichte für den Deutschunterricht (1982). - Heuser, Magdalene [ed.]. Paderborn : Schöningh. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.017-a)

7 Pusch, Luise F. (1979): „Der Mensch ist ein Gewohnheitstier, doch weiter kommt man ohne ihr - Eine Antwort auf Kalverkämpers Kritik an Trömel-Plötz' Artikel über 'Linguistik und Frauensprache'“. - In: Linguistische Berichte 63, p. 59 - 64.

8 Samel, Ingrid (1995): Einführung in die feministische Sprachwissenschaft. - Berlin : Schmidt, p. 10. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.NA.002)

9 Trömel-Plötz, Senta ; Guentherodt, Ingrid ; Hellinger, Marlis ; Pusch, Luise F. (1981): Richtlinien zur Vermeidung sexistischen Sprachgebrauchs. - In: Linguistische Berichte 71, S. 1-7. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23-a, Obj.-Nr. 3587). Previously published in 1980 Linguistische Berichte 69.

10 Ibid, p. 1.

11 Becker, Barbara (1983): Anrede „Frau” im Zeugnis. - In: Streit, Nr. 2, p. 29. Siehe press documentation: Frauen und Sprache II, Anredeform Frau - Fräulein in historischer Entwicklung, 1849-1993 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-KU.23.02).

12 See press documentation: Frauen und Sprache II, Anredeform Frau - Fräulein in historischer Entwicklung, 1849-1993 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-KU.23.02).

13 Tolmein, Oliver (2014): Wie das Binnen-I in die taz kam. Retrieved from: www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/journalismus-wie-das-binnen-i-in-die-taz-kam.976.de.html

14 Beide Geschlechter richtig ansprechen (2011). - In: Duden, Geschäftskorrespondenz, Mannheim. www.duden.de/sprachwissen/newsletter/Duden-Newsletter-vom-070111

15 Pusch, Luise F. (1984): Das Deutsche als Männersprache. - Frankfurt a. M. : Suhrkamp Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.021)

16 Pusch, Luise F. (1983): „Sie sah zu ihm auf wie zu einem Gott“ : Das DUDEN-Bedeutungswörterbuch als Trivialroman. - In: Pusch, Luise F.: Das Deutsche als Männersprache. Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp Verlag, p. 135 - 144. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.021)

17 Ibid, p. 144.

18 Gewalt durch Sprache : die Vergewaltigung von Frauen in Gesprächen (1984). - Trömel-Plötz, Senta [ed.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.010)

19 Ibid, p. 56.

20 Trömel-Plötz, Senta (2004): Sprache : Von Frauensprache zu frauengerechter Sprache. - In: Handbuch Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung : Theorie, Methoden, Empirie. - Becker, Ruth u.a.[ed.]. Wiesbaden : VS, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, p. 639. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.12.NA.001-a)

21 Antrag der Fraktion der GRÜNEN (Drucksache 11/3302 vom 26.02.1985) und Plenarprotokoll 11/56 des Hessischen Landtags vom 11. September 1985. See press documentation: Frauen und Sprache I, 1977-1994. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-KU.23.01, chapter 5)

22 Bericht Frankfurter Rundschau vom 21.11.1985. See press documentation: Feministische Debatten und Ereignisse, 1983. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-FE.03.02-1983, chapter 3.2, 26)

23 See press documentation: Frauen und Sprache I, 1977-1994. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-KU.23.01, chapter 1)

24 Das Gelächter der Geschlechter : Humor u. Macht in Gesprächen von Frauen und Männern (1996). - Helga Kotthoff [ed.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.028; various editions available)

25 Diehl, Elke (1994): An die -Innen gewöhnen : Sprache als Ausdruck gesellschaftlicher Realität. - In: Stiefschwestern : Was Ost-Frauen und West-Frauen voneinander denken. - Rohnstock, Karin [ed.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, p.131 – 141. (FMT- Shelf Mark: LE.01.068)

26 Deutscher Bundestag (1991): Maskuline und feminine Personenbezeichnungen in der Rechtssprache: Bericht der Arbeitsgruppe Rechtssprache vom 17. Januar 1990. - Drucksache 12/1041, p. 33f.. Retrieved fromr: dipbt.bundestag.de/doc/btd/12/010/1201041.pdf

27 Sahler, Gertrud (1993): Pressemitteilung Nr. 3 vom 20.01.1993, Kabinett beschließt sächliche Bezeichnung der Bundesministerien. BMFJ-Pressereferat [Hrsg.], Bonn. See press documentation: Frauen und Sprache I, 1977-1994. (PD-KU.23.01, chapter 5)

28 Hellinger, Marlies ; Bierbach, Christine (1993): Eine Sprache für beide Geschlechter : Richtlinien für einen nicht-sexistischen Sprachgebrauch. Bonn: Deutschen UNESCO-Kommission. www.unesco.de/fileadmin/medien/Dokumente/Bibliothek/eine_sprache.pdf

29 Ibid, p. 4.

30 Samel, Ingrid (1995): Einführung in die feministische Sprachwissenschaft. - Berlin : Schmidt. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.NA.002)

31 Ibid, p. 9.

32 Trömel-Plötz, Senta (1992): Der Ausschluss von Frauen aus der Universität. - In: Trömel-Plötz, Senta (ed): Vatersprache - Mutterland. - München : Frauenoffensive. p. 21-44. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.035)

33 Trömel-Plötz, Senta (2004): Sprache : Von Frauensprache zu frauengerechter Sprache. - In: Handbuch Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung : Theorie, Methoden, Empirie. - Becker, Ruth u.a. [ed.]. Wiesbaden : VS, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, p. 641. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.12.NA.001)

34 Bibel in gerechter Sprache : Taschenausgabe (2011). - Bail, Ulrike et al. [ed.]. Gütersloh : Gütersloher Verlagshaus. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.11.167)

35 Pusch, Luise F.: Generisches Femininum erregt Maskulinguisten, Teil 1. Retrieved from: www.fembio.org/biographie.php/frau/comments/generisches-femininum-erregt-maskulinguisten-teil-1 und Pusch, Luise F.: Generisches Femininum erregt Maskulinguisten, Teil 2: Plötzlich weiblich? Retrieved from: www.fembio.org/biographie.php/frau/comments/generisches-femininum-erregt-maskulinguisten-teil-2-ploetzlich-weiblich/

36 Hornscheidt, Lann (2014): Es war einmal ein X. - In: Die Zeit Nr. 50, 4. Dezember 2014. Retrieved from: www.zeit.de/2014/50/gender-studies-sprache-ohne-geschlecht-lann-hornscheidt

37 Vervecken, Dries; Hannover, Bettina (2015): Yes I can! Effects of gender fair job descriptions on children’s perceptions of job status, job difficulty, and vocational self-efficacy. - In: Social Psychology, 46, p.76 - 92.

All links last retrieved on 29.01.2018

Selective Bibliography

Sources Online

Sauter-Bailliet, Theresia (1977): Gibt es eine Frauensprache. - In: Courage, Nr. 10, S.37 - 38.

Zimmer, Dieter E. (1984): Die Der Das. - Zeit online.

Süssmuth, Rita (1987): Die Sprache kann so nicht bleiben. - Zeit online.

Burr, Elisabeth ( 09.04.2006 ): Bibliographie zur Genderlinguistik.

Recommendations

Key, Mary Ritchie (1972): Linguistic behaviour of male and female. - In: Linguistics, 88, p. 15 - 31.

Lakoff, Robin (1973): The logic of politeness : or, minding your P's and Q's. - In: Papers from the Ninth Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society. Corum, Claudia et al. [ed.]. Chicago : Department of Linguistics, University of Chicago. p. 292 - 305.

Pusch, Luise F. (1979): „Der Mensch ist ein Gewohnheitstier, doch weiter kommt man ohne ihr - Eine Antwort auf Kalverkämpers Kritik an Trömel-Plötz’ Artikel über 'Linguistik und Frauensprache'“. - In: Linguistische Berichte 63, p. 59 - 64.

Wex, Marianne (1979): "Weibliche" und "männliche" Körpersprache als Folge patriarchalischer Machtverhältnisse. - Hamburg : Wex. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KO.03.022) excerpt

Pusch, Luise F. (1984): Das Deutsche als Männersprache : Aufsätze und Glossen zur feministischen Linguistik. - Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.021)

Gewalt durch Sprache : die Vergewaltigung von Frauen in Gesprächen (1984). - Trömel-Plötz, Senta [ed.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.010)

Cameron, Deborah (1992): Feminism and linguistic theory. - Basingstoke : Palgrave. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.NA.004)

Feministischer Thesaurus : das Feministische Archiv und Dokumentationszentrum Köln legt den ersten feministischen Thesaurus auf Deutsch vor (1994). - Schwarzer, Alice [ed.] ; Scheu, Ursula [ed.]. Köln : FrauenMediaTurm. (FMT-Shelf Mark: NA.07.001)

Samel, Ingrid (1995): Einführung in die feministische Sprachwissenschaft. - Berlin : Schmidt. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.NA.002).

Das Gelächter der Geschlechter : Humor u. Macht in Gesprächen von Frauen und Männern (1996). - Helga Kotthoff [ed.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.23.028; various editions available)

Trömel-Plötz, Senta (2004): Sprache : Von Frauensprache zu frauengerechter Sprache. – In: Handbuch Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung : Theorie, Methoden, Empirie. - Becker, Ruth u.a. [ed.]. Wiesbaden : VS, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.12.NA.001)

Vervecken, Dries; Hannover, Bettina (2015): Yes I can! Effects of gender fair job descriptions on children’s perceptions of job status, job difficulty, and vocational self-efficacy. - In: Social Psychology, 46, p.76 - 92.

Press Documentation

Press documentation on Language and Gender: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Further FMT-Holdings (selection)

FMT-literature Language and Gender: PDF-Download

Related Topics

A More Female Church? Feminist Theology and Women in the Church

A More Female Church? Feminist Theology and Women in the Church

Women want to have a voice in the Church – and not only as members of the congregation, but in dialogue with God and all the way up to leading positions within the church hierarchy. › mehr

Female Makers: Pioneering Feminist Projects in Germany

Female Makers: Pioneering Feminist Projects in Germany

"We claim for an all-women room!" That was the slogan of the autonomous women's projects founded in the beginning of the 1970s. › mehr

Women's Studies and Feminist Theories

Women's Studies and Feminist Theories

Research about as well as by women recieve a distinct space in the academy. Finally, women's and gender studies led to the repeal of 'woman' as a political category. › mehr