“A room only for us, for women!” This was the credo of the autonomous women’s projects that were established with the advent of the women’s movement in the early 1970s. Thus, women took control of a variety of spaces: they launched women’s cafés, women’s pubs, and women’s centres in order to communicate without male interference and to respond to each other – instead of, as traditionally the case, to men. They founded women’s archives, women’s publishing houses, and women’s bookshops with the intention to rediscover and collect women’s knowledge and to be able to publish on ‘their’ subjects. The first women’s hotels and women’s education centres were also created during this time.

January 1973: The First Women’s Centre

Approximately 120 women establish Germany’s first women’s centre at the Hornstraße 2 in Kreuzberg, Berlin.1 The main initiators are the women’s group Brot und Rosen and the Frauengruppe der Homosexuellen Aktion Westberlin (HAW). With the centre’s establishment, the women of the HAW demonstratively split away from homosexual men and increasingly collaborate with groups from the women’s centre. From 24 March 1973, the centre is open daily.2 The first gynaecological self-exam takes place at the centre in November 1973 under the instruction of two American feminists (for more see text on woman’s health an patriarchal medicine).3

15 May 1973: Eviction of the First Women’s Squat

The era of squatting. Women and men from the alternative scene occupy vacant buildings (often the property of speculators) in order to obtain cheap living space. Women’s groups also start to occupy buildings. On 15 May 1973 in Frankfurt am Main, the first women’s squat is evicted by a hundred-strong police contingent and two water cannons. A group of young women – students and white-collar workers – had occupied an abandoned flat in the Freiherr-vom-Stein-Straße in order to live there as a ‘Frauenkollektiv’ [‘women’s collective’].4

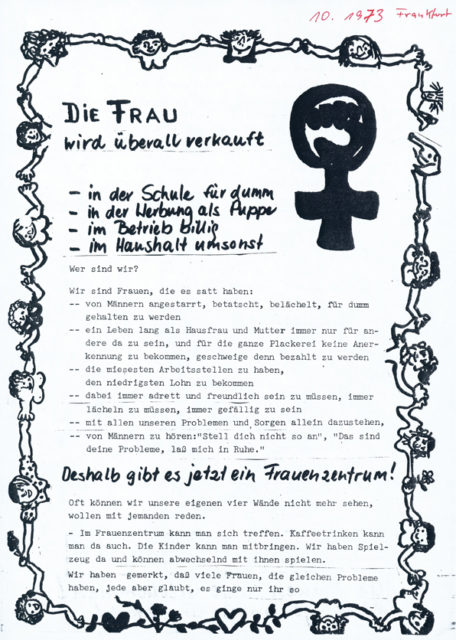

September 1973: Women’s Centres on the Rise

Germany’s second women’s centre is founded at the Eckenheimer Landstraße 72 in Frankfurt.5 The chief initiators are Weiberrat and the women’s group Revolutionärer Kampf. The centre is a meeting point and forum, and it soon launches its own campaigns: it extends an invitation to an Infoabend zur gynäkologischen Selbstuntersuchung, calls for joint demonstrations against § 218, and organises trips to the Netherlands for women who want abortions (prohibited in Germany).6 The women’s centres in Berlin and Frankfurt are the first of many that emergent feminists will launch over the next years. By 1977, almost 60 women’s centres will have been established in 38 cities.7

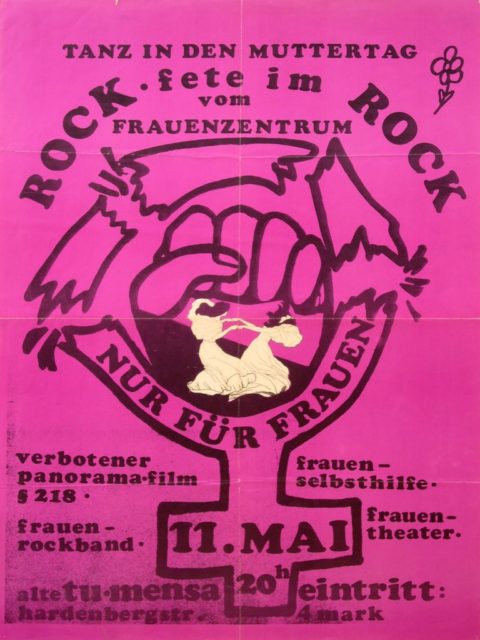

11 May 1974: First Women’s Festival in Berlin

The first public women’s festival – the Rockfete im Rock – takes place at the Technische Universität (TU) in Berlin. The event is organised by a group from the women’s centre in Berlin. Their pamphlet states: “We are all agreed that we want to celebrate this first public women’s festival amongst ourselves. We know – also from own experience – that our behaviour is freer when men aren’t present. For this reason, women, come alone this evening.” The organisers expect approximately 500 women; over 2,000 attend. Furthermore, an all-female band that had formed especially for the occasion performs: the Flying Lesbians. The Rockfete im Rock becomes an event and a political one at that.8

1974: Women Establish Publishing Houses

18 women from within the women’s movement establish Frauenoffensive in Munich, Germany’s first independent women’s publishing house.9 Frauenselbstverlag Berlin follows in the same year. The publishing house soon goes by the name Frauenpresse. From 1980, it is called sub rosa frauenverlag, and from 1986 Orlanda Frauenverlag (after Virgina Woolf’s novel Orlando10).11

Women from the women’s centre in Berlin organise the first two Frauenraubdrucke [‘pirated copies of women’s works’]. The aim: important (historical) feminist texts – which are very difficult to obtain and therefore largely unknown – are to be made available to the widest possible female readership. The women’s centre in Berlin reprints Frauenstaat und Männerstaat, a 1921 book by the researcher of matriarchy Mathilde Vaerting, as well as Der Mythos vom vaginalen Orgasmus by Anne Koedt.12 Soon thereafter, the Frauenselbstverlag Berlin likewise publishes Frauenstaat und Männerstaat as its first book. The demand is high.13

![Frauenkalender '75 (1974). - Bookhagen, Renate [Hrsg.] ; Schlaeger, Hilke [Hrsg.] ; Scheu, Ursula [Hrsg.] ; Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.] ; Zurmühl, Sabine [Hrsg.]. Berlin : Selbstverlag (FMT-Signatur: NA.09.013-1975) Frauenkalender '75 (1974). - Bookhagen, Renate [Hrsg.] ; Schlaeger, Hilke [Hrsg.] ; Scheu, Ursula [Hrsg.] ; Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.] ; Zurmühl, Sabine [Hrsg.]. Berlin : Selbstverlag (FMT-Signatur: NA.09.013-1975)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Frauenkalender_1975-480x640.jpg)

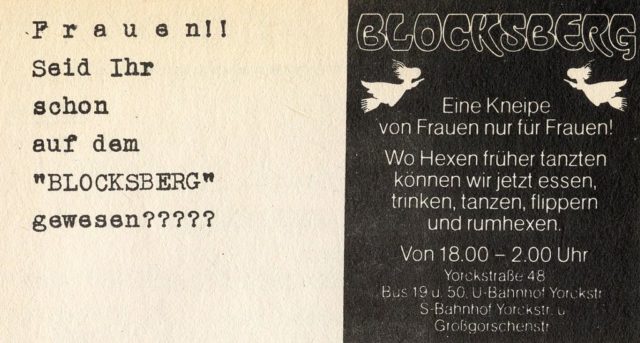

September 1975: First Women’s Pub opens in Berlin

The first women’s pub in Europe opens in the Yorkstraße in Kreuzberg, Berlin: the Blocksberg. Before long, the small pub is a meeting place for many Berlin women. Only two years after it opened, however, the Blocksberg is deep in debt and is forced to close following an argument between the two founders. Over the next years, many pubs that only admit women open across Germany.14

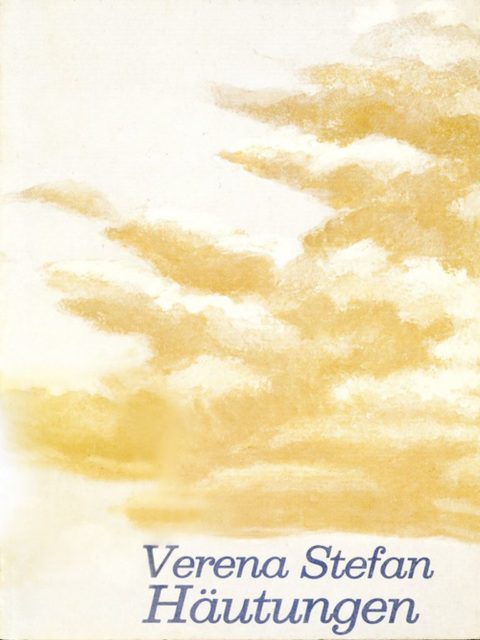

1975: Publication of the First Frauenkalender

The first Frauenkalender15 is published by the Berlin-based Frauenselbstverlag. Frauenoffensive publish their first book and their first women’s periodical. Verena Stefan’s novel Häutungen16 (Shedding, New York 1978) is published in German translation by Frauenoffensive in the same year. The book is a bestseller and for the first time provides the women’s publishing house with strong financial backing, making it possible for the publisher to disengage from its production and distribution partnership with the left-wing Trikont-Verlag.

3 November 1975: First Women’s Bookshop in Munich

Lillemor’s, the first women’s bookshop in Germany, opens in the Arcisstraße in Munich. The five founding members want to make feminist literature, and texts and books by women, available to women as well as to create a social space for women. One week later, the second women’s bookshop in Germany opens in Berlin: Labrys.17

December 1975: Publication of the Frauenjahrbuch 1975

The Frauenjahrbuch 75 is published on the initiative of the women’s centre in Frankfurt: “The idea of publishing a women’s yearbook goes back to experiences with women’s movements in other countries, the development of which we were able follow thanks to a large number of publications. The women’s yearbook should give us the opportunity to keep remembering and analysing the current state of the movement.“18

The all-female band Flying Lesbians produces their first and only album. The group had formed spontaneously in the previous year after the English all-female band booked for the Rockfete im Rock had cancelled. The LP is released in 1976 with the Munich-based publishing house Frauenoffensive with a first print-run of 5,000 copies.19

January 1976: Operating Autonomously

The first Frauenbuchvertrieb (FBV) [‘women’s booksellers’] is founded in Berlin. The idea: women’s projects should be able to operate autonomously, and in this instance that means that books published in the new women’s publishing houses should no longer be distributed by ‘Männervertrieben’ [‘men’s sellers’].20

April 1976: Female Activism

Four activists from the Lesbisches Aktionszentrum (LAZ) create the Amazonen-Frauenverlag in Berlin, which aims to “self-confidently and pro-actively represent the lesbian cause”. Jill Johnston’s analysis Nationalität Lesbisch22 (Lesbian Nation23, USA 1973) and Aimée Duc’s 1901 historical lesbian novel Sind es Frauen? are among the first books that the publishing house prints. The publisher exists until 1984 (see also text on lesbian women).25

Over the course of the year, further women’s publishers are established. After Frauenoffensive, the Frauenbuchverlag is set up in Munich (from the end of the ‘80s, under the name Antje Kunstmann Verlag) with the following motto: “Books for majorities who are treated like minorities”. In 1977 the publishing house already posts sales of 300,000 D-Mark – however, the six female staff are not yet able to pay themselves salaries from this sum.26 Critics accuse the publisher of cooperating with men and publishing works by male authors. The publishing house Frauenpolitik is established in Münster.27

8/9 May 1976: Female Writers Form Group

The publisher Frauenoffensive extends an invitation to the 1st Treffen Schreibender Frauen in Munich. Approximately 100 participants attend, among them well-known authors like Christa Reinig, Monika Sperr, and Hedi Wyss. The programmatic debate about ‘women’s literature’ and ‘women’s writing’ that had emerged with the establishment of the women’s publishing houses is continued.28

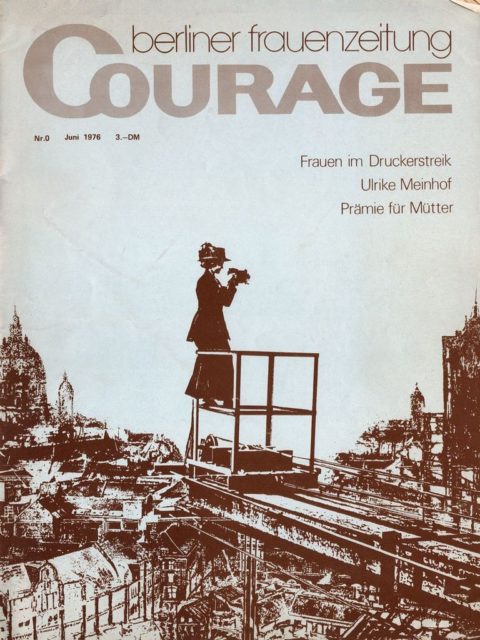

17 June 1976: Courage starts in Berlin

The first edition of the feminist magazine Courage is issued as an alternative to the Berliner Stadtzeitung. The magazine sees itself as a collective initiative that should reflect the entire spectrum of the women’s movement. The majority of its staff are not journalists and initially work on a voluntary basis. With the publication of EMMA, Courage will expand its distribution nationwide. Courage ceases publication in 1984.29

Summer 1976: Initiative for Professional Feminist Magazine

The journalist Alice Schwarzer – a household name since her TV-dispute with Esther Vilar30 and the publication of her bestseller Der kleine Unterschied31 – begins preparing a professional feminist magazine that is to hit newsstands. Schwarzer hopes to achieve an initial print run of 100,000 to 200,000 and writes a letter to all women’s centres, in which she urges all interested women to cooperate. “The magazine should be as generally understandable and popular as possible, i.e. broadly address the problems and interests of the majority of women and at the same time creatively and boldly advance the theoretical discussion of women’s rights.”32

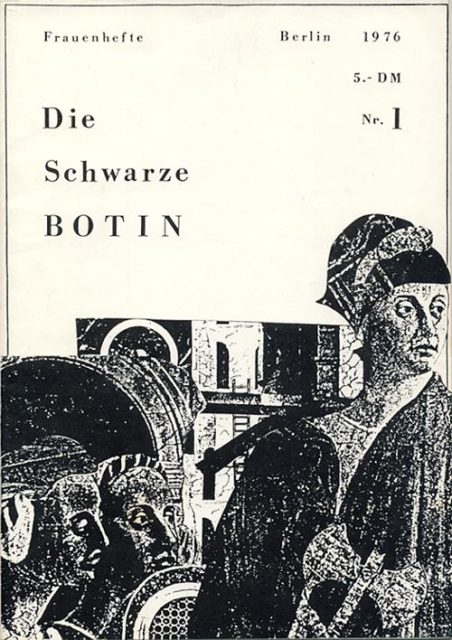

Autmn 1976: A Call for a Boycott

Three months before the publication of the first edition of EMMA, an Aufruf zum Informationsboykott [‘call for a boycott’] of EMMA appears in the Schwarze Boten.33 Among other things, it specifies: “We signatories call on all women’s groups, centres, and individual women not to place any materials, addresses, activities, or funds at the disposal of EMMA, in other words of Alice Schwarzer.“34 The signatories fear “… the imminent commercialisation of the women’s movement by ‘Emma’ as a commercial enterprise.” Courage joins the boycott and declares: “Solidarity can only exist in the women’s movement if all women are prepared to work together against women’s projects that, as a result of their masculine-capitalistic marketing, are detrimental to the women’s movement.“35

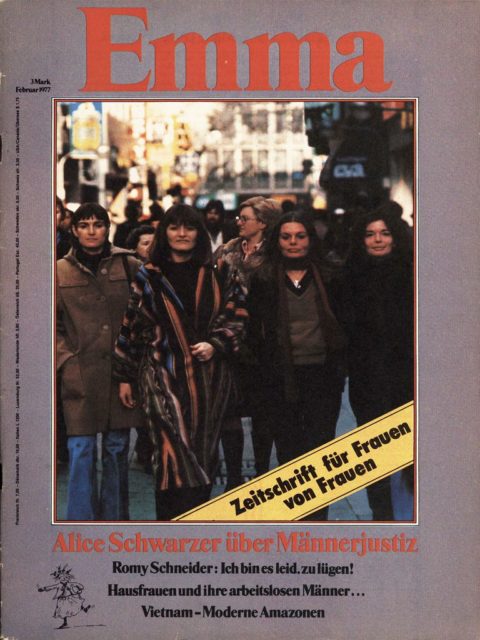

26 January 1977: Publication of the First EMMA

The first EMMA is published. Alice Schwarzer is publisher and editor in chief (first editorial). The magazine causes a furore. The first 200,000 copies are sold out within a week; 100,000 are reprinted. The media goes crazy. ZDF counts the missing commas; Bunte predicts that, at maximum, one more edition will be published; and the FAZ assumes that “in the long run there will be more explosive material for modern society [in the pages of EMMA] than in the wildest dreams of confused revolutionaries”.“36– EMMA is still being printed today, on a bi-monthly basis.

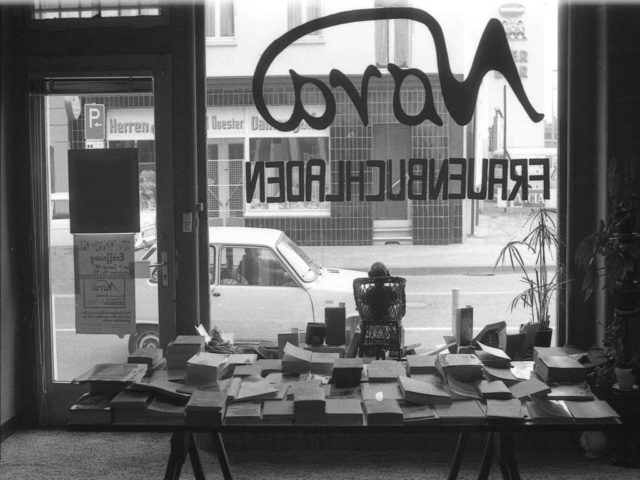

4 June 1977: Nora, Nora, Nora

The women’s bookshop Nora opens in Bonn.37

1978: Feminist Archive (FFBIZ) is Established in Berlin

The publisher Frauenoffensive extends an invitation to the first Internationale Feministische Verlagskonferenz in Munich. A result: for the first time, women’s publishers organise a joint press conference and present their books together at the Frankfurt Book Fair.38

The Feministische Frauenforschungs-, -bildungs- und Informationszentrum (FFBIZ) is established in Berlin. The archive starts to preserve the traces of the women’s movement. Reason: “Many groups active in the New Women’s Movement […] do not document their activities in a structured way in official files, but rather in working papers, minutes, pamphlets, posters, photos, badges, stickers, and many other ‘grey’ materials. In addition, there are records containing songs from demonstrations and women’s festivals.“39

The women’s bookshop Amazonas is established in Bochum. At the end of the 1980s, here and within Bochum’s lesbian community the idea for the magazine Ihrsinn – eine radikalfeministische Lesbenzeitschrift40,originated; it will be published nationwide from 1990 to 2004.41

1 August 1978: Münchner Frauenkneipe

The Münchner Frauenkneipe opens. Ten women who knew each other from other women’s working groups open the pub together. The pub provides exhibition space for ‘women’s art’ and encourages music-making. Two of the founders, who are employed as social workers, offer weekly, free counselling.42

1979: Women’s Media Shop Opens in Hamburg

![Wahlboykott? : Haben Frauen noch die Wahl? ; Eine Streitschrift zu den Wahlen '80 (1980). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.] ; Strobl, Ingrid [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauen-Verlag. (FMT-Signatur: ST.03.028-1980) Wahlboykott? : Haben Frauen noch die Wahl? ; Eine Streitschrift zu den Wahlen '80 (1980). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.] ; Strobl, Ingrid [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauen-Verlag. (FMT-Signatur: ST.03.028-1980)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/EMMA_Wahlboykott-479x640.jpg)

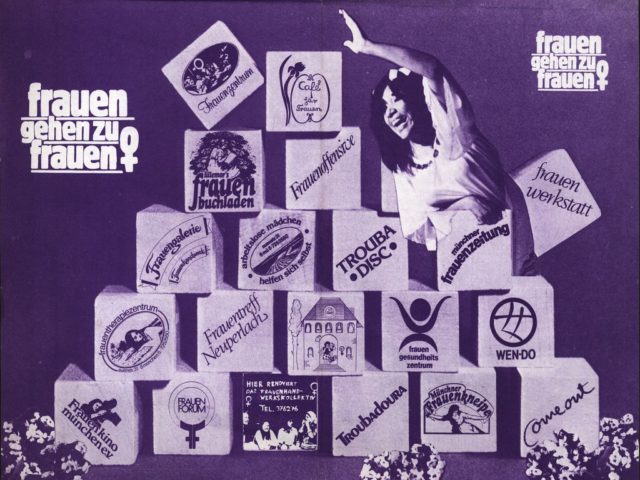

The umbrella organisation of feminist women’s projects Frauen gehen zu Frauen e. V. is founded.44

1 July 1979: Frauenbildungshaus Zülpich

The Frauenbildungs- und Frauenferienhaus Zülpich e. V. opens. The project was spearheaded by female students at Cologne’s Fachhochschule. The converted farm provides seminar rooms, overnight accommodation, and opportunities for leisure activities. Over 48,000 women have taken part in courses and events at the Frauenbildungs- und Frauenferienhaus Zülpich e.V. to date, and it celebrated its 35-year anniversary in 2014.45

1981: The First EMMA-Book

The EMMA-Verlag – which has published EMMA since 1977 – issues the first EMMA-book46 composed of selected articles from EMMA. In the same year, EMMA-Verlag also publishes Mein feministischer Alltag47 by Franziska Becker; this book is followed by Das kleine Mädchen, das ich war48 in 1983 and PorNO: die Kampagne, das Gesetz, die Debatte49 (find out more in our text about pornography) in 1988.

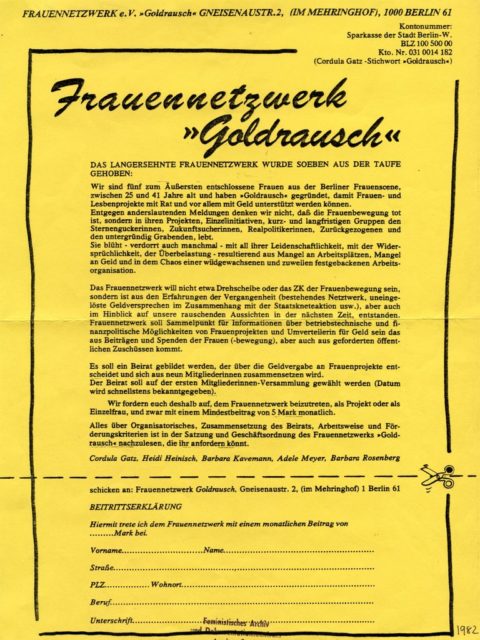

1982: Women’s Network Goldrausch

The women’s network Goldrausch is established in Berlin. The registered society still exists today, awards microcredit to start-ups and entrepreneurs, and is a member of Weiberwirtschaft eG. The financing of a photocopier for the Lesbenarchiv Berlin and the backing of the newspaper Lesbenstich50 are among the society’s first sponsored projects. So far, Goldrausch has promoted and supported 450 women’s companies and projects with approximately €850,000 (from membership fees and donations).51

1983: Women Only

The former hotel Schöne Aussicht in Charlottenberg, Rhineland-Palatinate becomes the Frauenlandhaus Charlottenberg e. V. is still a women’s conference and seminar house, a community centre, and a place where women can spend their vacations amongst themselves.

29 January 1983: National Meeting of the Women’s Archives

At the Bielefelder Frauenwoche, the first national meeting of the women’s archives takes place at the invitation of the Frauenarchiv Osnabrück; seven women from Osnabrück, Hamburg, and Frankfurt partake. A tradition of – initially biannual – women’s archive conferences develops, which eventually leads to the establishment of an umbrella organisation in 1994.52

8 March 1984: The FMT and its Beginning

The Feministisches Archiv und Dokumentationszentrum is established in Frankfurt. One of the first press releases states: “It is the intention of the Feministisches Archiv to document the unvarnished reality of women’s lives, their varied attempts at emancipation and liberation, and the theory of the radical women’s struggle, feminism. We want to thus reappraise as comprehensively as possible the history of ‘new feminism’ – already under threat now – as well as (in part) the history of first-wave radical feminism; contemporary history will, however, be given precedence.“53 In 1988, the archive moves to Cologne and in 1994 into the Bayenturm, a symbolic location in Cologne’s (male) history that provides the feminist archive with a dignified setting and lets it become, under its new name FrauenMediaTurm, a proud beacon of women’s history.

The library and study centre of the The library and study centre of the Archiv der deutschen Frauenbewegung e. V. likewise opens on 8 March in Kassel with the aim to collect documents relating to the historical women’s movement in Germany and to create the “possibility for historical feminist research and education”. 54

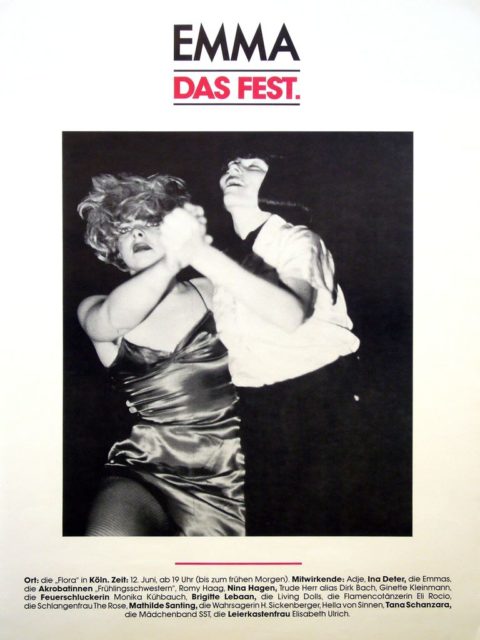

12 June 1987: EMMA Festival

In Cologne, EMMA celebrates its ten-year anniversary in the Flora, the city’s botanical gardens. Ina Deter and Dirk Back perform, among others, and the event is presented by Hella von Sinnen. Over 6,000 women take part in the hitherto largest women’s festival in Germany.55

1988: Women’s Cafe Endlich

The women’s café endlich opens in Hamburg, out of which the women’s hotel Hanseatin56 also emerges in 1995.

1989: Artemisia and Weiberwirtschaft

The women’s hotel Artemisia opens in Berlin. The Berlin-based Weiberwirtschaft is set up as a cooperative. Businesses headed by women establish themselves in the business park. The underlying idea: “To pool the initiative, the economic potential, and above all the entrepreneurial spirit of women and to give this idea a name and a space.“ Today Weiberwirtschaft boasts approximately 60 business for, and run by, women. With around 1,800 members, Weiberwirtschaft is Europe’s largest centre for female entrepreneurs.

What Happens Next?

After the ‘birth’ of women’s projects in the 1970s, starting in the 1990s women’s projects begin to ‘die off’. The reason for this is above all that the feminist agenda and its demands found their way into mainstream culture. For example, the fight against sexual harassment has made visiting pubs or hotel bars (from which women without male accompaniment would have been barred in the past) the new normal. Many women’s bars and restaurants have therefore become superfluous in their function as safe spaces and have closed because of a shortage of guests.

So-called ‘women’s literature’, which was previously only available in women’s bookshops, is part of the standard assortment in regular bookshops today. Most women’s bookshops have therefore either shut permanently or diversified their catalogues, so that they cannot really be described as pure women’s bookshops anymore. Only a handful of women’s bookshops survives, among them Lillemor’s in Munich.58

In March 2013 the first internet bookshop for “feminist, emancipatory, and lesbian/queer literature” is launched with FemBooks. There still exist approximately 15 German-language women’s publishing houses, five of which have their headquarters in Berlin.59

The Dachverband deutschsprachiger Lesben/Frauenarchive, -bibliotheken und -dokumentationsstellen e.V., (i.d.a.) (informieren, dokumentieren, archivieren), is founded in 1994. Approximately 40 institutions from Germany, Italy, Austria, Switzerland, and Luxembourg join in the following years. Within the network the idea of a connected database and presentation develops – and finally takes shape as Digitales Deutsches Frauenarchiv.

2018 Digitales Deutsches Frauenarchiv launches in Berlin, putting central documents of the Women’s Movements in Germany available online – and securing their digitalised versions for the future.

Sources

1 Als die Frauenbewegung noch Courage hatte : die "Berliner Frauenzeitung Courage" und die autonomen Frauenbewegungen der 1970er und 1980er Jahre : Dokumentation einer Veranstaltung am 17. Juni 2006 in der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Berlin (2007). - Notz, Gisela [ed.].Bonn : Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, p. 14. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ME.03.071)

2 HAW-Frauen : Eine ist keine - Gemeinsam sind wir stark : Dokumentation (1974). - Homosexuelle Aktion West-Berlin Frauengruppe [ed.]. Berlin : HAW-Frauengruppe, p. 33. (FMT-Shelf Mark: LE.11.025)

3 Schmidt, Roscha (1988): Frauengesundheit in eigener Hand : die feministische Frauengesundheitsbewegung. - In: Der große Unterschied : die neue Frauenbewegung und die siebziger Jahre. - Soden, Kristine von [ed.]. Berlin : Elefanten Press, p. 39. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.03.065)

4 Frauenbesetzung in der Freiherr-vomStein-Straße (1974). - In: Frauenzeitung Nr. 2, p. 13f.. see Pressedokumentation: Chronik der Neuen Frauenbewegung, 1973 (PD-FE.03.01-1973, chapter 3.2, 10)

5 Die Frau wird überall verkauft (1973). - look at flyer in image archive. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FB.05.024)

6 Entdecken wir uns selbst wieder! : Früher waren die Frauen mit ihrem Körper vertraut (1975). - Frauenzentrum Frankfurt [ed.], look at flyer in image archive. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FB-05.069), Frauen gemeinsam sind stark! : Weg mit § 218 (1975). - Frauenzentrum Frankfurt [ed.], see pamphlet in the FTM Image Archive. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FB.05.086) und Überfall auf das Frankfurter Frauenzentrum : Wir machen wieder eine Fahrt nach Holland - kommt alle mit! (1975). - Frauenzentrum Frankfurt [Hrsg.], see in the FTM Image Archive. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FB.07.117)

7 Adressliste von Frauengruppen und Frauenzentren in: Schwarzer, Alice (1973): Der "kleine Unterschied" und seine großen Folgen : Frauen über sich : Beginn einer Befreiung. - Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbücher. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.10.226; several editions available)

8 Strobl, Ingrid (1979): Von heute an gibt's mein Programm!. - In: EMMA, Nr. 12, S. 32. retrived from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45167

9 Münch, Friederike (1978): Hat die Alleinherrschaft der Männerverlage jetzt ein Ende?. - In: Emma, Nr. 1, p. 8. retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45144

10 Woolf, Virginia (1928): Orlando : eine Biografie. - Frankfurt am Main : Fischer. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.03.WOOL.009)

11 Orlanda : Über den Verlag. website not availbe at the moment.

12 Vaerting, Mathilde ; Koedt, Anne (1975): Frauenstaat und Männerstaat [Beigefügtes Werk : Der Mythos vom vaginalen Orgasmus]. - Frauenzentrum Berlin [ed.]. Berlin : Frauendruck 1. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.06.401)

13 Zirm, Marie-Theres (2008): Verlagswesen - eine Frage des Geschlechtes? : 1973-2008 : 35 Jahre Frauenverlage in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz im Kontext der Frauenbewegung. - Wien : o. V., p. 74. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ME.03.070)

14 Just, Renate (1977): Frauen, Bier und keine Männer. - In: Zeit-Magazin. see Pressedokumentation: Frauenkneipen, 1976-1987 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-FE.03.07)

15 Frauenkalender '75 (1974). - Bookhagen, Renate [ed.]; Lorez, Gudula [ed.]; Scheu, Ursula [ed.]; Schwarzer, Alice [ed.]; Zurmühl, Sabine [ed.].Berlin : Selbstverlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: NA.09.013-1975)

16 Stefan, Verena (1994): Häutungen.- München : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.03.108, several editions available)

17 see Pressedokumentation: Deutsche und ausländische Frauenbuchläden, 1974-1993. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ME.03.07)

18 Frauen-Verein [ed.] (1975): Frauenjahrbuch '75 - 1. ed. - Frankfurt am Main : Roter Stern. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.03.001-1975.[01])

19 Raber, Ralf Jörg (2010): Wir sind wie wir sind : Ein Jahrhundert homosexuelle Liebe auf Schallplatte. - Hamburg : Männerschwarm Verlag, p. 183.

20 Goettle, Gabriele (1976): Frauen gemeinsam sind stark : Interview mit Regina Krause vom Frauenbuchvertrieb in Berlin. - In: Die schwarze Botin, Nr. 1, p.31-34. (FMT-Shelf Mark: Z-Ü108)

21 Lesbischer Verlag gegründet! (1976). - In: Unsere kleine Zeitung von und für Lesben, Nr. 6, p. 25. (FMT-Shelf Mark: Z-L301:1976-6)

22 Johnston, Jill (1977): Lesben-Nation : Die feministische Lösung. - Berlin : Amazonen-Frauenverlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: LE.11.072; several editions available)

23 Johnston, Jill (1973): Lesbian Nation : the Feminist Solution. - New York : Simon & Schuster.

24 Duc, Aimée (1976): Sind es Frauen? : Roman über das 3. Geschlecht. - Berlin: Amazonen-Frauenverlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.03.DUC.001)

25 Zirm, Marie-Theres (2008): Verlagswesen - eine Frage des Geschlechtes? : 1973-2008 : 35 Jahre Frauenverlage in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz im Kontext der Frauenbewegung. - Wien : o. V., p. 95 u. 111. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ME.03.070)

26 Frauenbücher: „Lieber sich gesund schimpfen“ (1977). - Der Spiegel, Nr. 51, p. 177. retrievd from: magazin.spiegel.de/EpubDelivery/spiegel/pdf/40693939

27 See Pressedokumentation: Frauenverlage, Frauenbuchprojekte und Initiativen im Literaturbereich, 1974-1993. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ME.03.04, chapter 1)

28 Zirm, Marie-Theres (2008): Verlagswesen - eine Frage des Geschlechtes? : 1973-2008 : 35 Jahre Frauenverlage in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz im Kontext der Frauenbewegung. - Wien : o. V., p. 95. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ME.03.070)

29 Courage-Countdown : Zum letzten, zum dritten, zum zweiten, zum ersten, zero? (1984). - In: Courage, Nr. 20, p. 4-5. retrieved from: library.fes.de/courage/pdf/1984_20.pdf

30 ALICE contra ESTHER : 6.2.75 ARD. - See Pressedokumentation: Chronik der Neuen Frauenbewegung, 1975. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-FE-03.01-1975, chapter 3.1, 3)

31 Schwarzer, Alice (1973): Der "kleine Unterschied" und seine großen Folgen : Frauen über sich : Beginn einer Befreiung. - Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbücher. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.10.226; several editions available)

32 Schwarzer, Alice (1976). - Rundbrief Nr. 2, 13.06.1976. See Pressedokumentation: Chronik der Neuen Frauenbewegung, 1976. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-FE.03.01-1976, chapter 3.3)

33 Frauen-Presse : Kampf um Emma (1976). - In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 49, p. 221. retrieved from magazin.spiegel.de/EpubDelivery/spiegel/pdf/41124889

34 Konflikt um Alice Schwarzers neue Zeitung "Emma" (1976). - In: Courage, Nr. 3, p. 42. retrieved from: library.fes.de/courage/pdf/1976_03.pdf

35 Ibid.

36 Pressereaktionen auf Emma (1977). - In: Emma, Nr. 2, p. 5. retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45660

37 Sonntag, Sonja (1977): Der Frauenbuchladen. - In: EMMA, Nr. 12, p. 44. retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45143

38 Zirm, Marie-Theres (2008): Verlagswesen - eine Frage des Geschlechtes? : 1973-2008 : 35 Jahre Frauenverlage in Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz im Kontext der Frauenbewegung. - Wien : o. V., p. 95f.. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ME.03.070)

39 FFBIZ : Geschichte. retrieved from: www.ffbiz.de/ueber-uns/geschichte/index.html

40 Ihrsinn : eine radikalfeministische Lesbenzeitschrift. - Ihrsinn e. V. [Hrsg.]. Bochum, 1.1990 - 15.2004; damit Ersch. eingest.. (FMT-Shelf Mark: Z-L310)

41 Plogstedt, Sibylle (2006): Frauenbetriebe : vom Kollektiv zur Einzelunternehmerin. - Königstein/Taunus : Helmer, p. 226. (FMT-Signatur: AR.03.313) und Wie Ihrsinn entstanden ist (1990). - In: Ihrsinn, Nr. 1, p. 112. (FMT-Shelf Mark: Z-L310:1990-1-a)

42 Münchner Frauenkneipe mit Garten (1978). In: EMMA, Nr. 9,p. 44. retrerived from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45152

43 Über Bildwechsel. retried from: www.bildwechsel.org/info/de/ueberuns.html

44 frauen gehen zu frauen (1979). - Münchener Frauenzeitung. See Pressedokumentation: Chronik der Neuen Frauenbewegung, 1979. (FMT-Signaturhelf Mark Frauenbildungshaus Zülpich : Geschichte. retrieved from: www.frauenbildungshaus-zuelpich.de/images/Geschichte.pdf

46 Wahlboykott? : Haben Frauen noch die Wahl? ; Eine Streitschrift zu den Wahlen '80 (1980). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.] ; Strobl, Ingrid [ed.]. Köln : Emma-Frauen-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.03.028-1980)

47 Becker, Franziska (1984): Mein feministischer Alltag : Cartoons. - München : Dt. Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: KU.09.063)

48 Das kleine Mädchen, das ich war : Schriftstellerinnen erzählen ihre Kindheit (1983). - Strobl, Ingrid [ed.] [epilogue] ; Mitscherlich-Nielsen, Margarete [prologue]. Köln : Emma-Frauen-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: Ku.07.202)

49 PorNo : die Kampagne, das Gesetz, die Debatte (1988). - Schwarzer, Alice [ed.]. Köln : Emma-Frauen-Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: SE.09.059-1988)

50 Lesbenstich : eine Zeitung der Lesbenbewegung. - Berlin : Lesbenstichverlag, 0.1980; 1.1980 - 14.1993,1; damit Ersch. eingest.. (FMT-Shelf Mark: Z-L303)

51 Arbeitsplätze selber schaffen : Chaos und Organisation, Gratisarbeit und Staatsgelder, Liebe und Konflikte, Engagement und Überdruß (1983). - Plogstedt, Sibylle [ed.]. Berlin, p. 23. (FMT-Shelf Mark: AR.03.211) retrieved from: library.fes.de/courage/pdf/sh08.pdf und Goldrausch in Kürze. retrieved from: www.goldrausch-ev.de/wir-ueber-uns/goldrausch-in-kuerze

52 Archivetreffen. retrieved from: www.denktraeume.de/denktraeume-2/archiv/290-2/

53 Das feministische Archiv und Dokumentationszentrum - erste Anmerkungen zu Arbeitsweisen und Absichten (März 1984), Pressemitteilung. - Mitscherlich-Nielsen, Margarete ; Reinig, Christa ; Schwarzer, Alice [ed.], S. 2. Siehe Pressedokumentation: Presseartikel Feministisches Archiv und FrauenMediaTurm, 1984-2010. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-NA.05.05)

54 Eröffnung (1984). - Archiv der deutschen Frauenbewegung e. V. [ed]. see leaflet in the FTM Image Archive (FMT-Shelf Mark: FB.06.016).

55 EMMA - Das Fest (1987). - see poster in the FTM Image Archive. (FMT-Shelf Mark: PT.1987-06)

56 Frauenhotel Hanseatin : Über uns. retrieved from: www.hotel-hanseatin.de//hotel/ueberuns.html

57 Weiberwirtschaft eG. retrieved from: weiberwirtschaft.de/home/

58 The women's bookshops Lillemore's in Munich , Laura in Göttingen, Xanthippe in Mannheim and Thalestris in Tübingen - all established during the 1970s - still exist today.

59 Aktualisierte Information auf der Grundlage der Verlagslisten in: Taschenbuch Frauenpresse (2005). - RWE Energy [ed.]. - Remagen-Rolandseck : Rommerskirchen, p. 191ff.. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ME.01.NA.003-2005)

All internet links last retrieved on: 05.09.2018

Selective Bibliography

Recommendations

Arbeitskreis Autonomer Frauenprojekte Berlin [ed.] (1992): 20 Jahre und (k)ein bisschen weiser? Bilanz und Perspektiven der Frauenprojektbewegung. Bonn : Stiftung Mitarbeit. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.03.138)

Eva Brinkmann to Broxten, Claudia Fuchs u.a. [ed.] (1987): Ohne Netz und doppelten Boden. Frauenprojekte und Frauenpolitik in Hessen. - Frankfurt : Frauenbuchversand. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.03.085)

Margrit Brückner (1996): Frauen- und Mädchenprojekte. Von feministischen Gewißheiten zu neuen Suchbewegungen. Opladen : Leske und Budruch. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.93.113)

Frankfurter Frauen [ed.] (1975): Frauenjahrbuch 1975. Frankfurt am Main : Verlag Roter Stern. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.03.001-1975)

Renate Rieger [ed.] (1993): Der Widerspenstigen Lähmung? Frauenprojekte zwischen Autonomie und Anpassung. Frankfurt am Main, New York : Campus Verlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.03.121)

Alice Schwarzer (1981): 10 Jahre Frauenbewegung. So fing es an! Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag. (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.03.164-1981)

Press documentation

Press documentation on Female Projects: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Further FMT-Sources (selection)

FMT-literature Female Projects: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Women Who Work: Housework and Claim for Equal Pay

Women Who Work: Housework and Claim for Equal Pay

When the women’s movement started, housework was still by law a woman’s job. Feminists fought successfully for the abolition of this law. › mehr

Female Filmmakers

Female Filmmakers

Many young female filmmakers are active in the Women's Liberation Movement, addressing feminist issues in a variety of film genres. › mehr

The Female Artist: A Feminist View on Art and Photography

The Female Artist: A Feminist View on Art and Photography

In the 19070ies feminist artists challenged the male-dominated art world - and fought for the visibility of female artists. › mehr