Self-determination and knowledge of one’s own body – women’s health initiatives were directed against a patronizing and patriarchal medicine that made the male body the point of reference and declared the female body to be a deviation that was both medicalised and pathologised.

Women’s health initiatives began with the acquisition of knowledge about women’s bodies and the establishment of women’s health centres. They demanded a medicine that treated the whole person as well as more female doctors (in the 1970s, approximately 85% of gynaecologists are men.1) They denounced the patronizing medical treatment of women, which oscillated between over-treatment (e.g., the often-unnecessary removal of the uterus) and under-treatment (e.g., decades of neglected early breast cancer detection). Furthermore, women’s health initiatives complained that the male body was held to be the norm in the development of medications and called for a gender-aware view of disease. This led to the development of ‘gender medicine’, which is by now largely well-established.2

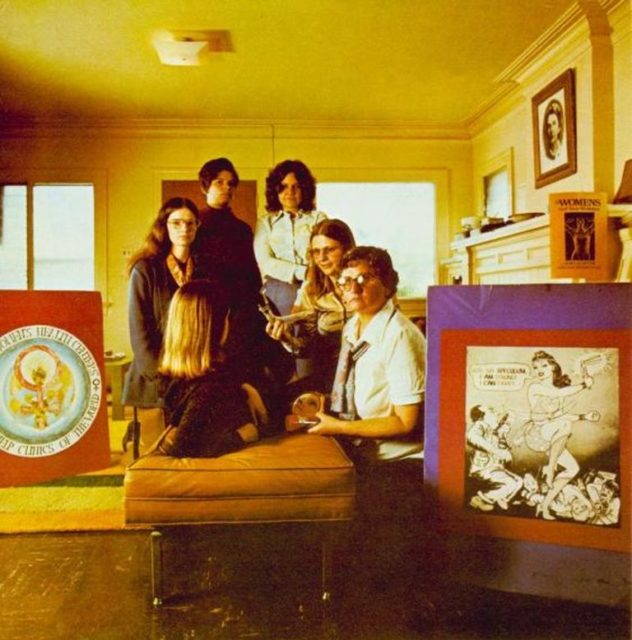

November 1973: Carol Downer’s Vaginal Self-examination

For the first time in Germany, the American Carol Downer demonstrates vaginal self-examination with the so-called speculum to 300 women at the Women’s Centre in West Berlin.3 Downer had previously conducted the first public self-examination at the Los Angeles Women’s Health Centre – which resulted in a police search and seizure of her materials (including the yoghurt pots that Downer had used to self-treat vaginal yeast infections). Downer and her colleague Colleen Wilson stand trial for “practicing medicine without a license.”4 The acquisition of knowledge about one’s own (female) body is fundamental to the emergence of women’s health initiatives.

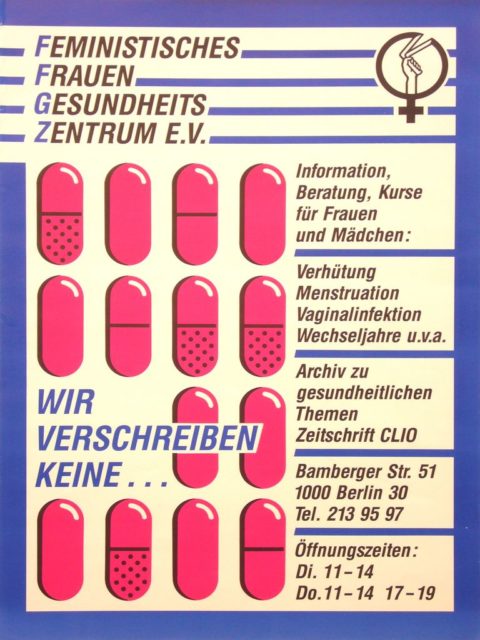

1974: Feminist Female Health Centre in Berlin

The Feministische Frauengesundheitszentrum (FFGZ) opens in Berlin.5 It is the first of its kind in Germany. The FFGZ embraces a holistic concept of health and a self-determined relationship with one’s own body: “Through self-help, we want to be in the position to be able to independently make choices about our bodies and sexuality.“6 Priorities: self-examination, conducting smear tests, cancer detection, conversations about sexuality and contraception, pregnancy tests and counselling, healthy diet.

1974: Mental Health and Gender Roles

Frauen – das verrückte Geschlecht7 (Women and Madness8, 1972) by the American professor of psychology and psychotherapist Phyllis Chesler is published. In this seminal study Chesler, co-founder of the National Women’s Health Network, argues that mental illnesses like depression or addiction are a response by women to their restrictive gender roles, in particular to abuse and violence. The book constitutes a crucial impulse for psychologists, analysts, and psychiatrists in the FRG. Mental health will become an additional key theme for women’s health initiatives.

September 1975: Publications on Women’s Health

The experiences of the women at the FFGZ Berlin are summarised in the booklet Hexengeflüster. Frauen greifen zur Selbsthilfe9, which is self-published by the centre. Other topics include the right to abortion, the high number of unnecessary hysterectomies (prescribed recklessly, predominantly to women over 40), the considerable side effects of the pill, and the pathologisation of menopause.

July 1976: The Feminist Health Magazine Clio

The feminist health magazine Clio10 is published for the first time by the Feministisches Frauengesundheitszentrum in Berlin. The preface to the first edition states: “Women need power! Control over our own bodies is a crucial step towards having this power!”11 The issue includes articles on the self-help conference in Göttingen, solidarity with abortion clinics in the Netherlands, or complaints about individual doctors. Clio is still published today (all volumes held by the FMT).

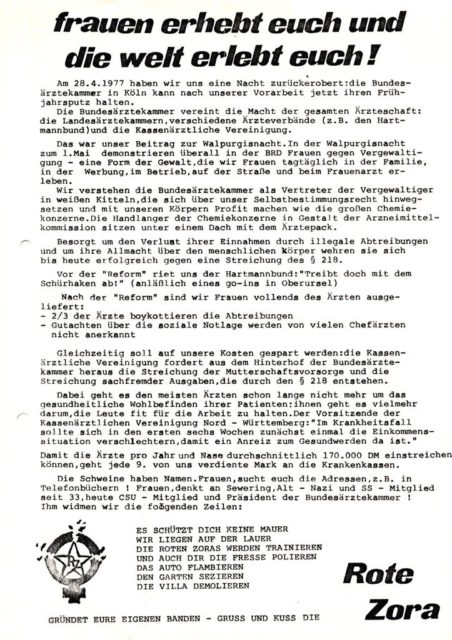

28 April 1977: Bomb Attack on the Medical Association

The militant women’s group Rote Zora, which sees itself as part of the leftist terrorist group Revolutionäre Zellen, launch a bomb attack on the building of the German Medical Association. They declare: “We see the German Medical Association as a representative of the rapists in white coats who disregard our right to self-determination!”12 The medical association’s official publication Deutsches Ärzteblatt will in retrospect consider the nascent women’s health initiatives in the Deutscher Herbst [‘German Autumn’] to be part of the terrorist scene.13

14 -16 June 1977: International Congress on Women’s Health

Women’s health initiatives increasingly network on an international scale. In Rome over 200 women from Europe, the USA, South America, and Australia gather for the first Internationaler Frauengesundheits-Kongress [‚International Congress on Women’s Health‘].14

1978: Feminist Health Centres Establish

The Feministisches Frauengesundheitszentrum Frankfurt is established.15 Over the next years, further centres in Hamburg, Bremen, and Cologne follow. Today 16 centres are organised in the Bundesverband der Frauengesundheitszentren.

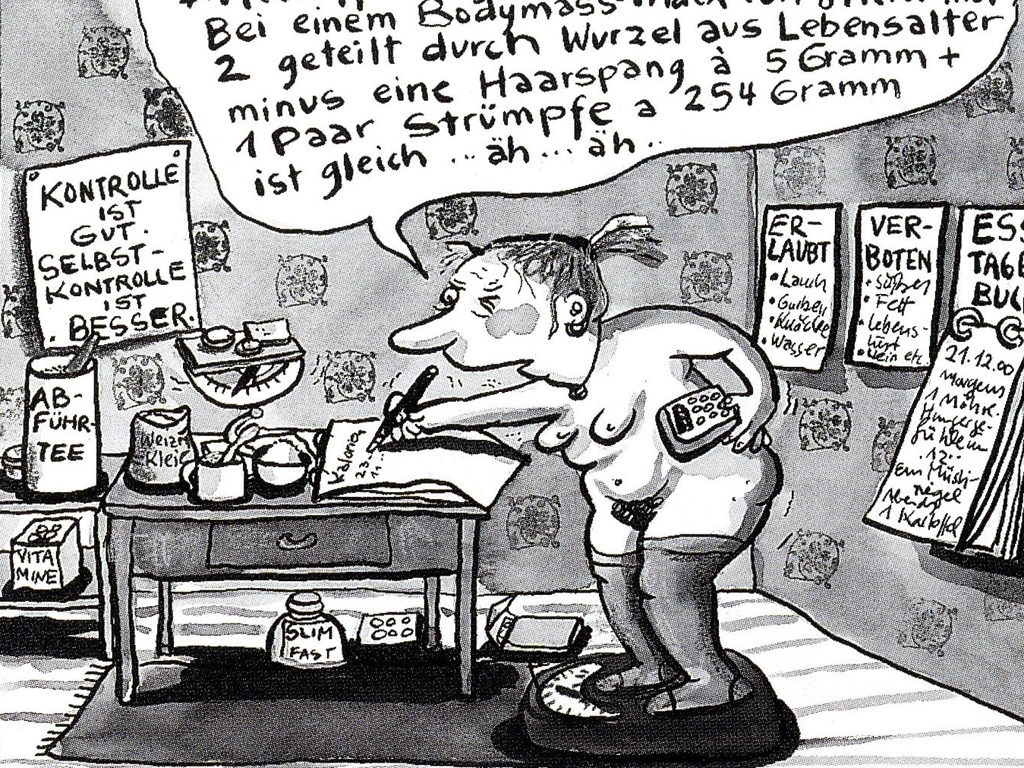

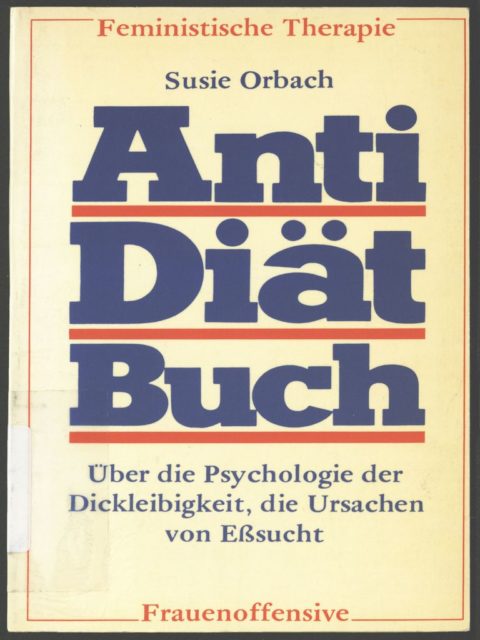

1979: Orbach – Fat is a Feminist Issue

The Anti-Diät-Buch16 by the British psychoanalyst Susie Orbach (Fat is a Feminist Issue17, 1978), is published in Germany; in this study, Orbach categorises the widespread phenomenon of eating disorders among women (from the obsession with dieting to obesity and anorexia) as a response to restrictive gender roles. Orbach criticises the massive pressure on women to be slim and beautiful and evaluates it as a reaction to the women’s emancipation movement: “The super-thin beauty ideal coincides so precisely with the emergence of the new feminist movement that it it makes one suspicious. It is hard not to see the ‘aesthetics of skin-and-bones’ as an attempt to counter women’s demands for more space in the world”18 The subject of eating disorders becomes a further central topic within the women’s health movement (see text about body image, dieting and eating disorders).

![Our Bodies, Ourselves : a Book by and for Women (1973). - Women's Health Book Collective [Hrsg.]. New York : Simon & Schuster. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.01.001) Our Bodies, Ourselves : a Book by and for Women (1973). - Women's Health Book Collective [Hrsg.]. New York : Simon & Schuster. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.01.001)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Our_bodies_ourselves-486x640.jpg)

1980: Our Bodies, Ourselves is Released in German

Unser Körper – unser Leben : ein Handbuch von Frauen für Frauen19 (Our Bodies, ourselves20, 1971) is published in Germany and addresses a variety of topics to do with women’s health from a feminist point of view: from contraception and sexually transmitted diseases, psychotherapy and medication, to nutrition and body image. Already at the time of its publication in the USA by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective 11 years previously, the book was perceived by its German readership to be an important milestone. The German edition reaches a circulation of 300,000 copies by the early 1990s; the second volume, published in 1988, is similarly successful.

1984: Feminist Magazine EMMA on Eating Disorders

![Durch Dick und Dünn (1984). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984) Durch Dick und Dünn (1984). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/EMMA_Durch_dick_und_duenn-480x640.jpg)

1986: WHO Adopts Ottawa-Charta

The World Health Organisation (WHO) adopts the so-called Ottawa-Charta. It defines health holistically as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”.24 The WHO’s departure from narrow, conventional terminology makes it easier for the women’s health movement to include women’s conditions in the health debate. Shortly thereafter, the WHO declares: “Women’s health must be granted the utmost attention and urgency.”25 Because: “Even in the richest countries in Europe, there are inequalities between the health care of men and of women, which are not being recognised.”26

What happens next?

Over the following years and decades, the insights and demands of feminists with respect to women’s health increasingly permeate medicine, politics, and society. In Germany a milestone in this regard is the Bericht zur gesundheitlichen Situation von Frauen, published in 2001 under the aegis of the Minister for Women Christine Bergmann (SPD). This women’s health report is the first review of (subpar) health care for women in Germany. It extends the conventional medical view and includes the living conditions of girls and women as causes of illnesses. The report takes up all the issues raised by the women’s health movement of the 1970s and shares its feminist critique. The report notes a disturbing lack of data in many areas, such as (of all things) gynaecological diseases. (Only in 1999 was a chair in gynaecology filled by a woman.)27 The consequences of the “epidemic proportions” of (sexual) violence against women and girls for their health are also virtually unexplored.28

With the advent of the 2000s, feminists are for the first time successful in raising awareness for (sexual) violence and its (psychosomatic) consequences as one of the greatest health risks for women within mainstream medicine. Since then, various projects have been working to sensitise doctors and nurses to the relevant symptoms and to cooperate with the women’s counselling centres. New alliances emerge.

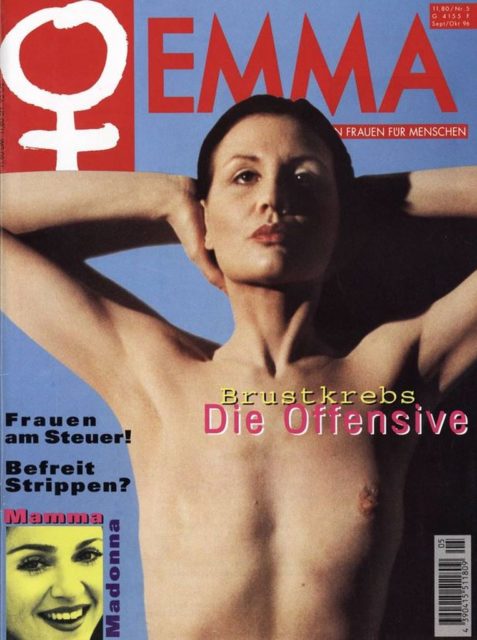

Women’s initiatives, which had been fighting since the mid-1990s against the criminal neglect of breast cancer research and for qualified and systematic early detection programmes in Germany, achieve a crucial success. In 1996 a cover story is published in EMMA, which denounces the ignorance of medicine and politics with regard to this ‘women’s disease’ as a “genocide of women”.29 While mammography screening programmes with highly qualified specialists have already been introduced in many European countries like the Netherlands, Great Britain, or Sweden, Germany lags behind – even though breast cancer is the deadliest of all cancers for women with 42,000 new cases and 18,000 deaths a year.30 Numerous breast cancer initiatives produce so much political pressure with their campaigns that in 2005 mammography screening for women between 50 and 69 is also introduced nationwide in Germany.31

In December 2002 the Charité hospital in Berlin establishes, together with the Deutsches Herzzentrum, the first professorship for gender medicine: Prof. Regina Regitz-Zagrosek now runs “Women Specific Heath Research with Focus on Cardiovascular Disease”. The Institut für Geschlechterforschung in der Medizin develops out of this in 2003.

Important German medical institutions like the Robert-Koch-Institut or the Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung set up posts for “gender and health”. In the meantime, a guideline is in force that states that medical testing ‘should’ also include female patients.

Today ‘gender medicine’ – although not yet accepted in Germany as a compulsory subject for medicine – is established as standard-knowledge at universities and doctor’s practices. And the hegemony of the ‘demigods in white’ – criticised by the women’s health movement – also appears to be broken: today almost every second doctor (45%) is female.33

References

1 Burgert, Cornelia; FFGZ e. V. (2014): Zwischen Selbstbestimmung und Fremdbestimmung - 40 Jahre Frauengesundheit in eigener Hand?!. - In: Clio, Nr. 79, November 2014, p. 5. (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-F002-2014-79)

2 Ibid., p. 4f..

3 Schmidt, Roscha (1988): Frauengesundheit in eigener Hand : die feministische Frauengesundheitsbewegung. - In: Der große Unterschied : die neue Frauenbewegung und die siebziger Jahre. - Soden, Kristine von [Hrsg.]. Berlin : Elefanten Press, p. 39. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.065)

4 Schwarzer, Alice (2007): EMMA : die ersten 30 Jahre. - München : Heyne, p. 169. (FMT Shelf Mark: ME.03.060)

5 Burgert, Cornelia; FFGZ e. V. (2014): Zwischen Selbstbestimmung und Fremdbestimmung - 40 Jahre Frauengesundheit in eigener Hand?!. - In: Clio, Nr. 79, November 2014, p. 3. (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-F002-2014-79)

6 Die Neue Frauenbewegung in Deutschland : Abschied vom kleinen Unterschied (2008). - Lenz, Ilse [Hrsg.]. Wiesbaden : VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, p. 123. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.NA.002) und Lauterbach, Jutta; Scharf, Doris; Schultz, Dagmar (1977): Es geht um unseren Körper als Ganzen. - In: Courage. 1977, Nr. 11, p. 13-18. Retrieved from: library.fes.de/courage/pdf/1977_11.pdf

7 Chesler, Phyllis (1974): Frauen - das verrückte Geschlecht?. - Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.05.006-1974)

8 Chesler, Phyllis (2005): Women and madness. - New York : Palgrave Macmillan. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.05.006-2005)

9 Hexengeflüster : Frauen greifen zur Selbsthilfe (1975). - Frauenzentrum Die Rasenden Höllenweiber [Hrsg.]. Berlin : Selbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.006-1). The first edition of the second volume is published the following year: Hexengeflüster 2 : Frauen greifen zur Selbsthilfe (1976). - Ewert, Christiane [Hrsg.] ; Karsten, Gaby [Hrsg.] ; Schultz, Dagmar [Hrsg.]. Berlin : Frauenselbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.006-2)

10 Clio : die Zeitschrift für Frauengesundheit. - Berlin : Feministisches Frauen-Gesundheitszentrum, Nr.: 0.1976 - (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-F002)

11 Vorwort (1976). - In: Clio : Zeitschrift für Frauengesundheit, Nr. 0, p. 2. (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-F002:1976-0)

12 frauen erhebt euch und die welt erlebt euch! (1977). - Rote Zora [Hrsg.], siehe Flugblatt im Bildarchiv. (FMT-Signatur: FB.07.102)

13 Wolff, Ulrich (1979): Von Feministinnen, Hexen, Kräutern und Gynäkologen. - In: Deutsches Ärzteblatt, Nr. 7, p. 454, see Pressedokumentation: Medizin II : Gesundheitsinitiativen und Prävention, 1972-1994. (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-KO.07.02, Kapitel 1). Wolff writes: “The prototype of aggressive-political minorities that appear destructive are the Feministische Frauengesundheitszentren (FFGZ), which have been operating in the FRG and in West Berlin for two years.”

14 Frauengesundheits-Kongreß in Rom (1977). - In: EMMA, Nr. 9, p. 59. Retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45140

15 10 Jahre FFGZ : Feministisches Frauengesundheitszentrum Frankfurt 1978-1988 : Dokumentation (1988). - Feministisches Frauen-Gesundheits-Zentrum [Hrsg.]. Frankfurt am Main : Selbstverlag, p. 11. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.061)

16 Orbach, Susie (1979): Anti-Diätbuch : Über die Psychologie der Dickleibigkeit, die Ursachen von Eßsucht. - München : Verlag Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.009-Bd.1)

17 Orbach, Susie (1978): Fat is a feminist issue : the anti-diet guide to permanent weight loss. - New York : Paddington Press.

18 Orbach, Susie (1984): Wenn der Körper zu Welt wird. - In: Durch Dick und Dünn. - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag, S. 87. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)

19 Unser Körper, unser Leben : ein Handbuch von Frauen für Frauen (1984). - Lorenzen, Kerstin [Hrsg.] ; Menzel, Beate [Hrsg.]. "Bd." 1, Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.01.002-Bd.1)

20 Our Bodies, Ourselves : a Book by and for Women (1973). - Women's Health Book Collective [Hrsg.]. New York : Simon & Schuster. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.01.001)

21 Durch Dick und Dünn (1984). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)

22 Ibid., p. 6.

23 Hofman, Barbara: Frankfurter Zentrum für Ess-Störungen : seit 25 Jahren durch Dick und Dünn, p. 6. Retrieved from: www.selbsthilfe-frankfurt.net/downloads/publikationen/leitartikel_shz_winter_12.pdf

24 Verfassung der Weltgesundheitsorganisation. Retrieved from: www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19460131/201405080000/0.810.1.pdf

25 Wiener Erklärung über die Investition in die Gesundheit von Frauen in den mittel- und osteuropäischen Ländern, 1994, p. 1. Retrieved from: www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/114238/E93952G.pdf

26 Women’s Lives and Health in Europe : A Dialogue Across Borders : Documentation of the Conference in Bad Salzuflen, Germany 28th September - 1st October 2000, p. 12. Retrieved from: www.gesundheit-nds.de/ewhnet/Documentations/Bad_Salzuflen.PDF

27 Louis, Chantal (2003): Dossier : Gesundheit ; der lange Marsch der Frauen durch die Institutionen. - In: EMMA, Nr. 5, p. 64. Retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45393

28 Bericht zur gesundheitlichen Situation von Frauen in Deutschland : Eine Bestandsaufnahme unter Berücksichtigung der unterschiedlichen Entwicklung in West- und Ostdeutschland (1999). - Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend [Hrsg.]. p. 275. Retrieved from: www.gesundheit-nds.de/downloads/Frauengesundheitsbericht.pdf

29 Filter, Cornelia (1996): Dossier : Brustkrebs ; Genozid. - In: EMMA Nr. 5, p. 76 - 93. Retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45351

30 Ibid., p. 76.

31 Ist das Screening wirklich ein Fehler? (2014). - In: EMMA, Nr.5, p. 65. Retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/59836

32 Bericht zur gesundheitlichen Situation von Frauen in Deutschland : Eine Bestandsaufnahme unter Berücksichtigung der unterschiedlichen Entwicklung in West- und Ostdeutschland (1999). - Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend [Hrsg.]. S. 124. Retrieved from: www.gesundheit-nds.de/downloads/Frauengesundheitsbericht.pdf

33 Ärzteblatt (2014): Ärztestatistik : Mehr Ärztinnen, mehr Angestellte. Retrieved from: www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrichten/58336/Aerztestatistik-Mehr-Aerztinnen-mehr-Angestellte

Date of the last linkcheck: 29.01.2018.

Selective Bibliography

Documents online

Durch Dick und Dünn (1984). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)

Ottawa-Charta zur Gesundheitsförderung (1986). - Weltgesundheitsorganisation [Hrsg.].

Bericht zur gesundheitlichen Situation von Frauen in Deutschland : Eine Bestandsaufnahme unter Berücksichtigung der unterschiedlichen Entwicklung in West- und Ostdeutschland (1999). - Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend [Hrsg.].

Filter, Cornelia (1996): Dossier : Brustkrebs ; Genozid. - In: EMMA Nr. 5, p. 76 - 93.

Louis, Chantal (2003): Dossier : Gesundheit ; der lange Marsch der Frauen durch die Institutionen. - In: EMMA, Nr. 5, p. 64 - 70.

Hofman, Barbara: Frankfurter Zentrum für Ess-Störungen : seit 25 Jahren durch Dick und Dünn.

Recommendations

Chesler, Phyllis (1974): Frauen - das verrückte Geschlecht?. - Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.05.006-1974)

Hexengeflüster : Frauen greifen zur Selbsthilfe (1975). - Frauenzentrum Die Rasenden Höllenweiber [Hrsg.]. Berlin : Selbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.006-1)

Hexengeflüster 2 : Frauen greifen zur Selbsthilfe (1976). - Ewert, Christiane [Hrsg.] ; Karsten, Gaby [Hrsg.] ; Schultz, Dagmar [Hrsg.]. Berlin : Frauenselbstverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.006-2)

Clio : die Zeitschrift für Frauengesundheit. - Berlin : Feministisches Frauen-Gesundheitszentrum, Nr.: 0.1976 - (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-F002)

Orbach, Susie (1979): Anti-Diätbuch : Über die Psychologie der Dickleibigkeit, die Ursachen von Eßsucht. - München : Verlag Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.009-Bd.1)

10 Jahre FFGZ : Feministisches Frauengesundheitszentrum Frankfurt 1978-1988 : Dokumentation (1988). - Feministisches Frauen-Gesundheits-Zentrum [Hrsg.]. Frankfurt am Main : Selbstverlag, S. 11. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.061)

Unser Körper, unser Leben : ein Handbuch von Frauen für Frauen (1984). - Lorenzen, Kerstin [Hrsg.] ; Menzel, Beate [Hrsg.]. "Bd." 1, Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.01.002-Bd.1)

Schultz, Dagmar (1997): Die Entwicklung der Frauengesundheitszentren in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und ihre Bedeutung für die Gesundheitsversorgung von Frauen. - Berlin : Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.160-1)

Frauengesundheit in Theorie und Praxis : feministische Perspektiven in den Gesundheitswissenschaften (2010). - Mauerer, Gerlinde [Hrsg.]. Bielefeld : Transcript. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.229)

Gender-Medizin : Krankheit und Geschlecht in Zeiten der individualisierten Medizin (2014). - Gadebusch Bondio, Mariacarla [Hrsg.] ; Katsari, Elpiniki [Hrsg.] ; Fischer, Tobias [Hrsg.]. Bielefeld : Transcript. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.07.251)

FMT Presse Documentation

Press Documentation on Women's Health and Patriarchal Medicine: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Selected FMT-Sources (lists)

Selected literature Women's Health and Patriarchal Medicine: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Body Image: The Fight Against Dieting and Eating Disorders

Body Image: The Fight Against Dieting and Eating Disorders

From the mid-1970s, feminists began to problematise the tyranny of trying to become slender and its consequences for women. › mehr

Female Makers: Pioneering Feminist Projects in Germany

Female Makers: Pioneering Feminist Projects in Germany

"We claim for an all-women room!" That was the slogan of the autonomous women's projects founded in the beginning of the 1970s. › mehr

Prostitution - A 'Job Like Any Other'?

Prostitution - A 'Job Like Any Other'?

For some, it is “the oldest trade in the world” – for others, a violation of human dignity and 'white slavery'. › mehr