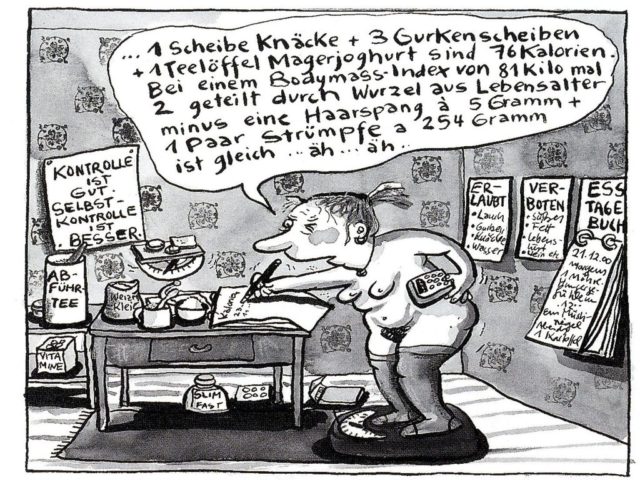

From the mid-1970s, feminists began to problematise the ‘Schlankheitsdiktat’ – the tyranny of being or trying to become slender – and its consequences for women. The already significant social pressure on women to be slim was only amplified by the rise of the women’s movement. Feminists interpreted this phenomenon as a response to women’s aspirations to “take up more space in the world”. And they demanded: “Dear sisters, let’s stop complaining and fasting, let’s fight instead.”1

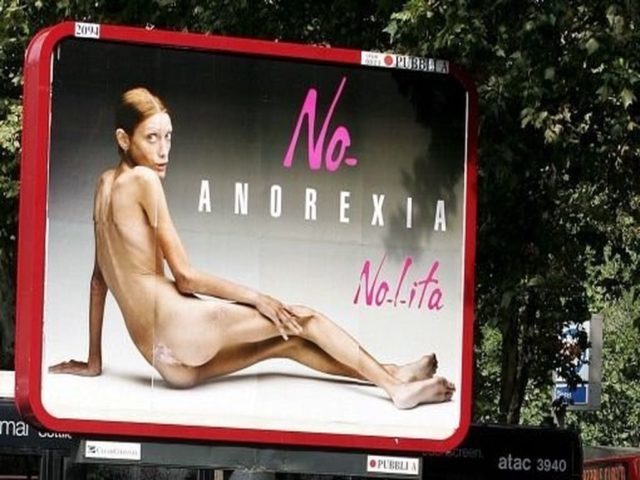

From the late 1970s, feminists sounded the alarm because it was by now obvious that the problem had reached dramatic proportions: many of the women – and especially girls – who were dieting obsessively had developed life-threatening syndromes. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa were endemic, and about every one in five girls was dying of malnutrition or its subsequent effects. From the mid-1980s, experts established the first centres for eating disorders in Germany, at which they not only treated those affected, but also addressed the connection between eating disorders and gender roles and implemented preventive measures. In the meantime, the public had become aware of the epidemic extent of eating disorders, and there were first counter-movements like, for example, the ban on anorexic models in Spain and France.

April 1978: The Standartised Female Body

One year after the magazine’s foundation, the feminist magazine EMMA thematises the pressure on women to have a standardised, slim body. In Sie sind ein Elefant, Madame… , Friederike Münch describes the “Vermessung der Frau” [“measurement of woman”] by the fashion and textile industry. Dress-sizes that fit women without the ‘ideal size’ are not available; instead, the industry produces clothes for an idealised, standard figure. And they do so even though the research institute Hohenstein – which specialises in textiles and clothing – had determined that almost half of women in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) wear a dress size 44 or larger.2

1979: Orbach – Fat is a Feminist Issue

The British psychoanalyst and journalist Susie Orbach publishes her Anti-Diät-Buch3 (Fat is a Feminist Issue4, 1978). Her book is the first comprehensive feminist analysis of the relationship between eating disorders and women’s roles. Orbach declares: “The fact that compulsive eating is over-whelmingly a woman’s problem suggests that it has something to do with the experience of being female in our society.”5 Women – who are subjected to constant criticism of their bodies and whose worth is defined by their physique – negotiate the conflict with their gender role on and through their bodies: being fat as rebellion against an unattainable beauty ideal; eating to counter internal emptiness; a layer of fat as protective armour against helplessness in a male-dominated world.

Orbach moreover establishes a link between the increasingly ruthless tyranny of slimness and the women’s movement: “The super-thin beauty ideal coincides so precisely with the emergence of the new feminist movement that it makes one suspicious. It is hard not to see the ‘aesthetics of skin-and-bones’ as an attempt to counter women’s demands for more space in the world.”6 Orbach’s book proves to be very popular and quickly becomes a classic (Orbach’s Anti-Diätbuch II7 will be published in 1982).

In the year of the publication of Orbach’s book, the 4. Berliner Sommeruniversität der Frauen organises an event for women suffering from compulsive eating or anorexia. The concept is based on Susie Orbach’s Fat is a Feminist Issue. Due to positive feedback at the conclusion of the summer university, it is decided that the Berlin women’s anti-diet group plenum should be retained, and regular meetings organised.8

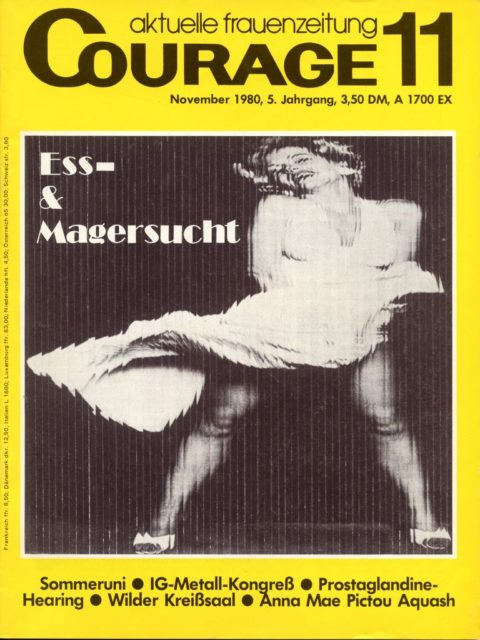

1980: Body Image and Public Space

Warum sollen wir Dicken uns dünne machen? Klage gegen den Schönheitsterror9 edited by Martina Bick, is published and rapidly becomes a classic among the books critical of the (social) norm of slimness and diet crazes. It states: “Maybe the ‘public’ woman ought not to take up so much space, quite literally? Women were allowed to take up space as long as they restricted themselves to the hearth and home […]. The space that women occupy – and are allowed to occupy – becomes problematic and contentious when this division of labour no longer functions, when women demand to be employed and paid according to their qualifications, when they demand influence commensurate with their occupation. The more substantial their professional roles become, the more important it becomes that they are thin.”10

The feminist magazine Courage takes up the subject of compulsive eating and anorexia in a dossier. Firsthand reports are printed alongside excerpts from Susie Orbach’s seminal text; the dossier makes suggestions for further reading as well as reference to the establishment of self-help groups.

1982: Case Studies on Anorexia Nervosa

Der goldene Käfig – das Rätsel der Magersucht11 [The Golden Cage: the Enigma of Anorexia Nervosa, 1978] by Hilde Bruch is published. The German psychoanalyst – who in 1933 emigrated first to England and then to the USA – had begun to conduct research into childhood obesity already in 1937. She encountered the phenomenon of anorexia nervosa for the first time in 1929. At the time, medical science assumed there were purely physical causes such as hormonal imbalances; later, psychoanalytical explanations (“oral fixation” etc.) were added.

Hilde Bruch, who presented 70 case studies in her book, focuses on psychological explanations: “The deeper underlying problem is personality disorder: self-esteem, identity, and independence suffer from deficits.”12 Bruch recognised: “These women are terribly afraid to be incompetent, a nothing, to not get or even deserve respect.”13 A particularly frequently affected group: “unusually good, successful, and promising girls”, who break under the weight of the expectations placed on them. Bruch’s book becomes a seminal text on the subject.

1982: The Fitness Trend Reaches Germany

The ‘strong woman’ body image comes into vogue, presumably as a concession to the women’s movement. The American actress Jane Fonda – who sees herself as a feminist – becomes a world-renowned female fitness guru, e.g. with her bestselling The Workout Book14. Fonda admits to suffering from an eating disorder for decades and simultaneously promotes a new beauty ideal: that of a not only slim, but also toned and athletic female body. However, the lengths women have to go to in order to achieve this ideal only increase. This fitness trend – which includes body building – finally also reaches Germany. At the beginning of the 1980s, major German newspapers like the Spiegel or the Stern15 increasingly report about the trend.

![Durch Dick und Dünn (1984). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984) Durch Dick und Dünn (1984). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/EMMA_Durch_dick_und_duenn-480x640.jpg)

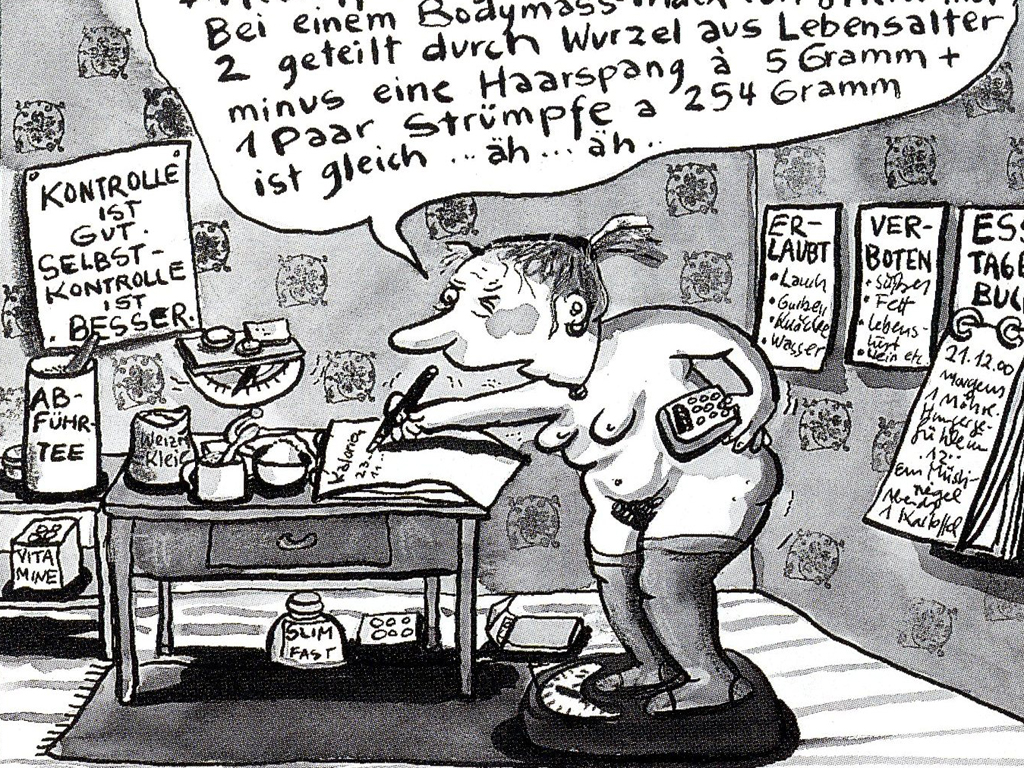

1984: Eating Disorders Become a Political Issue

The EMMA special issue Durch Dick und Dünn is published and raises the “alarm: a new female disease!” The issue brings together seminal texts on the subject, e.g. by Susie Orbach, Susan Brownmiller, and Alice Schwarzer. The latter interprets rampant anorexia and bulimia among women as a response to expansive emancipation: “Whereas men take up space, women make themselves thin!” And she declares: “It seems that, just at a time when we women have managed to loosen or even break external shackles, new internal shackles have tightened around us. And that one of the worst internal shackles is this obsession with thinness, which has many more consequences than we dare to surmise.“16 Eating disorders and their societal causes and functions now finally become a political issue. Initiated by the EMMA campaign, the first counselling centres are set up. (see our online text on women’s health and patriarchal medicine).

1985: Bulimia – A New Eating Disorder

A further book on the topic of eating disorders is published and focuses on a new phenomenon: bulimia. In Die heimliche Sucht, unheimlich zu essen17, the journalist Maja Langsdorff systematically addresses the subject of bulimia after she determined that the “symptoms of bulimia are largely unknown, even among doctors and psychologists”.18 Langsdorff had encountered this new form of female eating disorder after she had taken up contact with a self-help group for eating-disordered women, more and more of which are now emerging.

1986: The Foundation of Self Help Centres

Educators and therapists set up the Frankfurter Zentrum für Essstörungen, which follows Susie Orbach’s anti-diet approach. Other centres like Dick und dünn in Berlin and the eating-disorder counselling centre Kabera in Kassel soon follow. Some of the centres provide care on a voluntary basis and fight for public recognition and funding for years. The centres not only offer individual and group counselling in their own offices, but establish contacts with schools and clinics and develop brochures in order to build a broad prevention and counselling network. Today 15 such centres are active in Germany. They are organised in the Bundesfachverband Essstörungen (BFE) and partly publicly financed.

What happens next?

At the end of the 1990s, the problem – and with it the question of the media’s responsibility for female (body) image – reaches German politics. Other countries had already previously taken action: In England, the British Medical Association investigates the relationship between (painfully) thin role-models and rampant eating disorders amongst young girls. The Doctor’s Association demands: “Editors should take more responsibility by showing a more realistic range of women’s bodies instead of choosing extremely thin women as role models.”19 In June 2000, the British Minister for Women Tessa Jowell summons fashion designers, editors-in-chief, and industry representatives to the first Body Image Summit.20 In February 2001, in England and the USA self-help groups and ministries of health jointly call the first Eating-Disorder Week.

Spain also acts: the Minister of Health Celia Villalobos provided almost five million D-Mark for a campaign against anorexia and bulimia. The formerly anorexic top model Nievez Alvarez gives an account of her illness to parliament. As a result, Barcelona Fashion Week prohibits models who wear below a size 40.21

In December 2007, EMMA and the Federal Minister of Health Ulla Schmidt (SPD) launch a campaign against the obsession with slimness in Germany: Leben hat Gewicht.

Leading women from advertising, fashion, media, and medicine — including Susie Orbach — come to Berlin in order to take a stand against the deadly women’s addiction and to advise on measures. A first step, resulting from the conference: on 11 July 2008, the umbrella organisations covering the German fashion industry sign a Kodex gegen den Schlankheitswahn, in which they pledge to “correct” the “unhealthy body image” that dangerously thin models convey. Only models with a BMI of at least 18.5 are to be allowed to walk on German catwalks.

In December 2015, France legally bars fashion shows and agencies from employing models with a BMI under 19.22

Although German politics seem to have since forgotten about eating disorders, the figures continue to be alarming: according to the Dr. Sommer-Studie 2016 by the youth magazine Bravo, only half (52%) of 12-year-old girls are happy with their bodies — in 2006 it was still two-thirds (66%). One in ten 11-year-olds and one in four 12-year-olds surveyed said they had gone on a diet before. 78% of the respondents stated that there was a connection between “popularity and being thin”.

References

1 Warum sollen wir Dicken uns dünne machen? : Klage gegen den Schlankheitsterror Frauen schreiben auf (1980). - Bick, Martina [ed.]. Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, p. 133. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.024)

2 Münch, Friederike (1978): Sie sind ein Elefant, Madame.... - In: EMMA, Nr. 4, p. 56. Retrieved from: http://www.emma.de/lesesaal/45147#pages/57

3 Orbach, Susie (1982): Anti-Diätbuch : Über die Psychologie der Dickleibigkeit, die Ursachen von Eßsucht. - München : Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.009-Bd.1)

4 Orbach, Susie (1978): Fat is a feminist issue : the anti-diet guide to permanent weight loss. - New York : Paddington Press.

5 Orbach, Susie (1982): Anti-Diätbuch : Über die Psychologie der Dickleibigkeit, die Ursachen von Eßsucht. - München : Frauenoffensive, p. 14. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.009-Bd.1)

6 Orbach, Susie (1984): Wenn der Körper zu Welt wird. - In: Durch Dick und Dünn. - Schwarzer, Alice [ed.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag, p. 87. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)

7 Orbach, Susie (1984): Anti-Diätbuch : Eine praktische Anleitung zur Überwindung von Eßsucht. - München : Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.009-Bd.2)

8 Autonomie oder Institution : Über die Leidenschaft und Macht von Frauen (1981). - Berliner Sommeruniversität für Frauen / Dokumentationsgruppe [Hrsg.]. Berlin : Selbstverlag, p. 535. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.03.009-04)

9 Bick, Martina (1980): Warum sollen wir Dicken uns dünne machen? : Klage gegen den Schönheitsterror. Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, p. 133. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.024)

10 Ibid., p. 133.

11 Bruch, Hilde (1989): Der Goldene Käfig : Das Rätsel der Magersucht. - Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.060)

12 Bruch, Hilde (1984): Magersucht. - In: Durch dick und dünn, Schwarzer, Alice [ed.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag, p. 51. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)

13 Ibid., p. 52.

14 Fonda, Jane (1983): Jane Fondas Fitness-Buch. - Frankfurt am Main : Krüger.

15 Stark, Stramm, Fit und Frei (1982). - In: Der Stern vom 18.11.1982, p. 67.

16 Schwarzer, Alice (1984): Dünne machen. - In: Durch dick und dünn, Schwarzer, Alice [ed.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag, p. 6. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)

17 Langsdorff, Maja (1995): Die heimliche Sucht, unheimlich zu essen. - Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.007-1995)

18 Langsdorff, Maja (1984): „Stoff für eine Story?“. - In: Durch dick und dünn, Schwarzer, Alice [ed.]. Köln : Emma-Frauenverlag, p. 84. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.091-1984)

19 British Medical Assocation (2000): Eating disorders, body image and the media. - London: BMJ Books.

20 Landzettel, Marianne (2001): England und Spanien handeln!. - In: EMMA, Nr. 1, p. 55. Retrieved from: http://www.emma.de/lesesaal/45377#pages/54

21 Louis, Chantal (2001): Der Körper wird zum Schlachtfeld. - In: EMMA, Nr. 1, p. 48. Retrieved from: http://www.emma.de/lesesaal/45377#pages/47

22 Berufsverbot : Frankreich verbannt Magermodels vom Laufsteg. - In: Der Spiegel vom 18.12.2015. Retrieved from: http://www.spiegel.de/panorama/justiz/berufsverbot-frankreich-verbannt-magermodells-vom-laufsteg-a-1068451.html

Date of the last linkcheck: 26.01.2018

Selective Bibliography

Documents online

Münch, Friederike (1978): Sie sind ein Elefant, Madame .... - In: EMMA, no. 4, pp. 56 - 57.

Ess- & Magersucht (1980). - In: Courage, Nr. 11, pp. 15 - 31.

Brügge, Peter (1981): Heraus aus der muskulären Insolvenz. - In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 6, pp. 198 - 199.

Dossier : Hungersucht (2001). - In: EMMA, no. 1, pp. 42 - 61.

Drakulic, Slavenka (2006): Schlachtfeld Frauenkörper. - In: EMMA, no. 5, pp. 50 - 54.

Recommendations

Orbach, Susie (1979): Anti-Diätbuch : Über die Psychologie der Dickleibigkeit, die Ursachen von Eßsucht. - München : Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.009-Bd.1)

Bick, Martina (1980): Warum sollen wir Dicken uns dünne machen? : Klage gegen den Schönheitsterror. Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag, S.133. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.024)

Orbach, Susie (1982): Anti-Diätbuch : Eine praktische Anleitung zur Überwindung von Eßsucht. - München : Frauenoffensive. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.009-Bd.2)

Bruch, Hilde (1989): Der Goldene Käfig : Das Rätsel der Magersucht. - Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.060)

Langsdorff, Maja (1995): Die heimliche Sucht, unheimlich zu essen. - Frankfurt am Main : Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.09.007-1995)

MacRobbie, Angela (2010): Top Girls : Feminismus und der Aufstieg des neoliberalen Geschlechterregimes. - Wiesbaden : VS, Verlag für Sozialwissenschaft. (FMT Shelf Mark: FE.10.052)

Orbach, Susie (2010): Bodies : Schlachtfelder der Schönheit. - Zürich : Arche-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.03.080)

Penny, Laurie (2012): Fleischmarkt : weibliche Körper im Kapitalismus. - Hamburg : Edition Nautilus. (FMT Shelf Mark: KO.01.120)

FMT Press Documentation

Press Documentation on The Fight Against Calorie Counting and Eating Disorders: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Selected FMT-Sources (lists)

Selected literature The Fight Against Calorie Counting and Eating Disorders: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Women's Health and Patriarchal Medicine

Women's Health and Patriarchal Medicine

Self-determination and knowledge of one’s own body – women’s health initiatives were directed against a patronizing and patriarchal medicine that made the male body the point of reference while the female body was both medicalised and pathologised. › mehr

Feminist Debates on Sexuality and Love

Feminist Debates on Sexuality and Love

It was the women’s movement that questioned the function of power in sexuality and unmasked the fact that love disguises power structures. › mehr

Sexual Harassment - the Long Way to Sex Crime Legislation

Sexual Harassment - the Long Way to Sex Crime Legislation

Sexual harassment in the workplace became a public issue in Germany in the late 1970s, studies and debates have followed until it finally became a part of the sex crime legislation. › mehr