When EMMA first broke a long-held taboo in 1978 by reporting about sexual abuse, the reaction was – silence. Also from the victims themselves. It would take another five years before feminists established the first self-help group: Wildwasser. In the same year, the first girls’ refuge was opened in Germany. 32 years later, policymakers finally also take action.

April 1978: EMMA – Breaking the Taboo

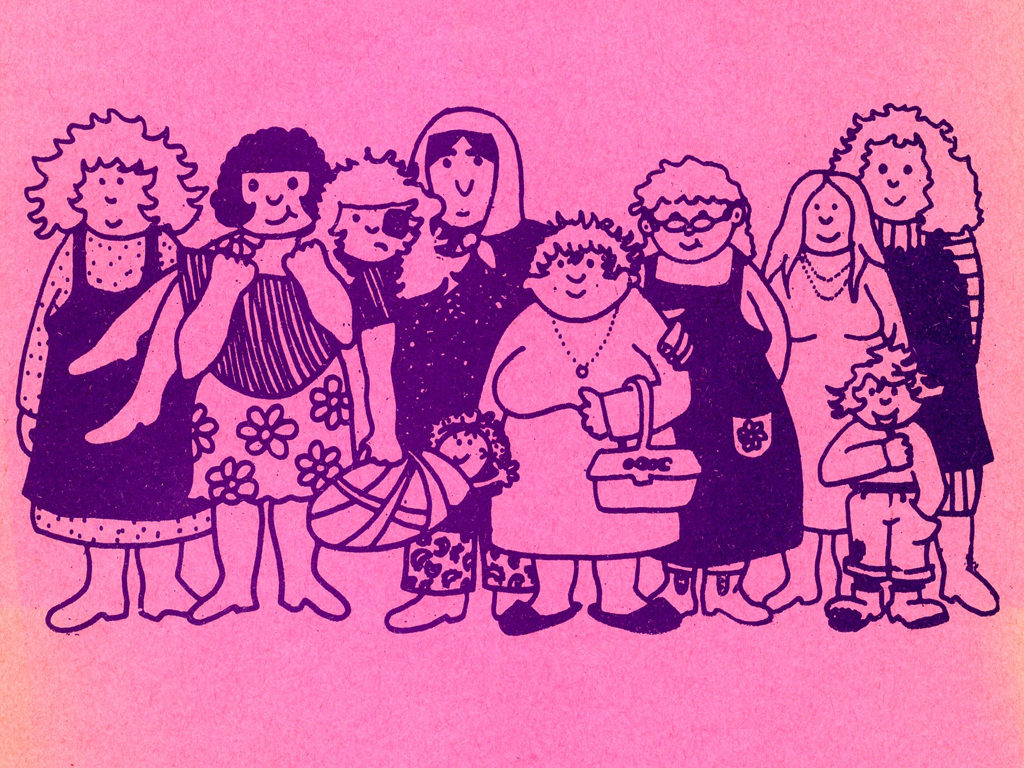

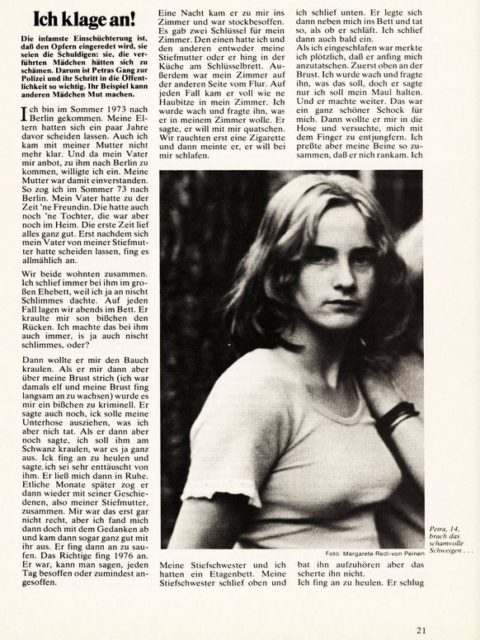

In the article Das Verbrechen, über das niemand spricht, EMMA reports about the sexual abuse of girls (and, more rarely, boys) by their own (step-)fathers. The magazine writes: “One of the biggest taboos and also one of the greatest crimes in our male-dominated society: fathers who assault their daughters, who are completely at their fathers’ mercy!” The magazine lets one of these girls – 14-year-old Petra – talk about her abuse at the hands of her father. With her mother, Petra fled from her father to the women’s refuge in Berlin.

EMMA attempts to throw light on the extent of sexual abuse, which was still largely undetermined: “There are hardly any figures. The few studies that exist only let us estimate the extent of the problem: three quarters of all sexually abused children (predominantly girls) knew their offenders; more than every one in four children reported that their abuser was their own father or stepfather.” These ratios are later confirmed. At the same time, EMMA points to the tragic role of mothers, who often stay silent about the abuse out of fear, dependence on the offender, or even out of a sense of rivalry with their daughters.

The article simultaneously challenges the claims of ‘progressive’ sexologists, who deny that there is a power imbalance between victim and perpetrator, argue for abolishing the incest paragraph (§176) in German criminal code, and make the case for sex acts between adults and children to remain exempt from punishment under certain circumstances. EMMA launches an appeal: “We ask girls who are affected to no longer stay silent! Girls who have no one who will help them defend themselves should contact us immediately.” The editors barely receive any response to this appeal at the time. The issue is apparently still so taboo that hardly any victims dare to speak out.

1979: Demand for the Abolition of § 176

More and more frequently, openly paedosexual men speak to the media and call for the abolition of §176, which penalises sex acts between adults and children. Their claim: children have their own sexual needs that are denied by ‘prudish, bourgeois society’. According to these men, as long as no ‘real’ violence is used, paedosexuals are fulfilling children’s needs.

In the taz, several openly paedosexual authors demand – unchallenged – the abolition of laws that penalise sex acts between adults and children. For example, in the article Pädophilie: Verbrechen ohne Opfer1, the homosexual Olaf Stüber declares: “I love boys” and calls for a reform of paedophilia laws in the name of the “sexual revolution”. “A liberalisation – in this case a reduction of the so-called ‘age of consent’ – can only be a first, tactical step. (…) We have to move away from crippled, state-mandated normality”. The similarly openly paedosexual Peter Merer asks: “Child molester? (…) We love children, with and without clothes. Sex legislation and your morality turn people who love children into criminals. When people love children, oppression disappears.”2

The educator and drug counsellor Peter Hartleb, who had been sentenced by the district court in Marburg to two years and three months in prison for the sexual abuse of a girl, is permitted to publish his ‘Gnadengesuch’, ‘petition for clemency’ in the taz. According to the taz, Hartleb was wrongly convicted because “in December 1976 Peter had a consensual petting session with a six-year-old girlfriend”.3 Demand for the abolition of §176 is also called for in the name of ‘liberal sex morals’ in other ‘progressive’ media outlets, including by renowned sexologists.

1980: The Best Kept Secret by Florence Rush

The Best Kept Secret – Sexual Abuse of Children is published in the US by the American social worker Florence Rush.4 Rush laments the ‘epidemic-like’ abuse of girls and boys, stating: “[…] I’ve come to know that child molestation by a trusted family friend or relative, as well as a stranger, is in no way unique. It is time we face the fact that the sexual abuse of children is not an occasional deviant act, but a devastating commonplace fact of everyday life.”5 The German translation – Das bestgehütete Geheimnis – sexueller Kindesmissbrauch – is published two years later with Sub-Rosa-Frauenverlag. (more about it in our text on feminist projects in Germany).

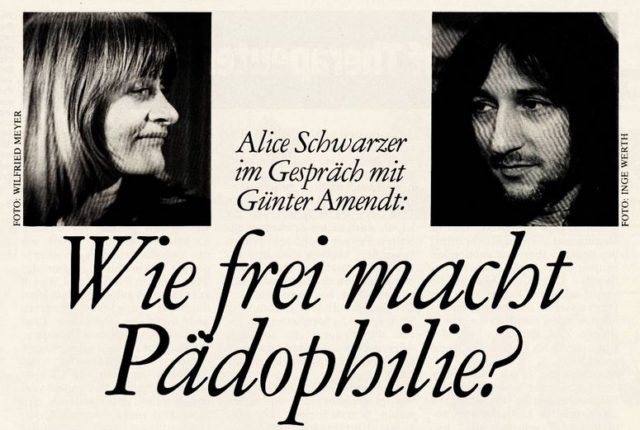

April 1980: Schwarzer/Amendt Conversation – § 176 is Not Abolished

Alice Schwarzer conducts an interview with Günter Amendt for the EMMA article Wie frei macht Pädophilie? The background to their conversation: under the influence of the paedosexual lobby, the SPD wants to abolish §176 as part of the reform of sex crime legislation, with the FDP – their liberal coalition partner – signalling their support. The conversation between Schwarzer and Amendt takes exception to this. Amendt, a well-known teacher and the author of the sex-ed book Sexfront, distances himself from the abolition of §176 during the conversation because “it’s about unequal relationships, domination, and ultimately exploitation”. Amendt is part of the left-wing scene in which the acceptance of paedosexuality is most widespread. The discussion is widely received. §176 is not abolished.

June 1980: Indianerkommune at the Greens‘ Party Conference

At the Greens’ Party conference in Dortmund (the political party had been founded in January 1980), members of the Nuremberg-based Indianerkommune – a commune in which paedosexual adults and minors live together – give a presentation that promotes paedosexuality as an ‘anti-bourgeois’ and child-friendly lifestyle. In the following years, paedosexuals will take advantage of the Green Party and their advocacy of ‘sexual minorities’ to introduce their demands into election programmes. In the AG Schwule und Päderasten (SchwuP), homosexual men openly work together with paedosexual men and embrace their demand for ‘non-violent’ sex with children to be exempt from punishment.6

June 1983: 1st Girl’s Refuge in Germany

The first girls‘ refuge in Germany opens in Hamburg. Girls who have been victims of sexual abuse and/or ill-treatment within their families are able to live in sheltered flats or houses maintained by specialists. The ten spots available in the new refuge are filled after only a couple of weeks. The girls’ refuge in Hamburg is set up under the auspices of the city and is financed by the Landesjugendamt, or state-run social services. In other cities, feminist initiatives are by and large the ones campaigning for more girls’ refuges. (see also our text on women’s refuges). In 1988 the first autonomous girls’ refuge opens in Munich. The project was launched by the Initiative Münchner Mädchenarbeit (IMMA). Every second one in two of the approximately 150 girls that live in a girls’ refuge comes from a Muslim background. Therefore, from 1985 special refuge projects for girls with this cultural background are established, e.g. the Papatya in Berlin or the Rosa in Stuttgart (1986).7

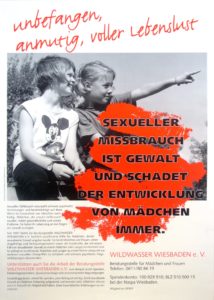

October 1983: Self-help Group Wildwasser

Women set up the self-help group Wildwasser in Berlin.8 The group, which initially moves into a small office in an occupied house in the Potsdamer Straße, helps girls and women who have been victims of sexual abuse to cope with the psychological and physical effects and, if necessary, with harrassment by their abusers. The foundation marks the beginning of feminists’ self-organised work with victims of abuse. Awareness grows for just how many girls and boys fall victim to sexual abuse within their close social circles. Similarly, the growth of educational work goes hand in hand with increased understanding of the serious and often lifelong consequences of abuse for victims, as Wildwasser explains in an information leaflet: self-destructive behaviours, addictions, depression, anxieties.9

Soon thereafter, Wildwasser groups are established in further cities across the FRG. Wildwasser in Berlin is grant-aided from 1985 – at first on a municipal and later on a national level as a pilot project. Over the years, the groups become more professional and develop into counselling centres with specialist staff. As of 2017, there are 130 Wildwasser counselling centres across Germany.

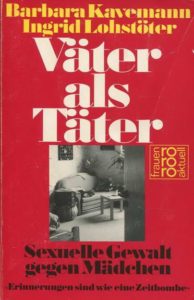

1984: Sexual Assaults within the Family

The book Väter als Täter by Barbara Kavemann and Ingrid Lohstöter is published in June.10 The sociologist and lawyer, respectively, had previously published an expert’s report about the nature and extent of sexual abuse for the government’s sixth Jugendbericht. They characterise the extent of sexual abuse as “unimaginably large”, whereby “in particular girls” fall victim to “sexual assaults within the family”.11

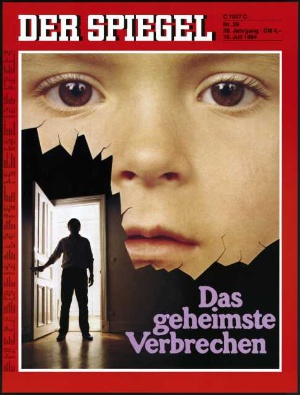

On 16 July 1984, the Spiegel issues a cover story about sex abuse within the family: Das geheimste Verbrechen.12 Shortly beforehand, the American magazine Newsweek13 had also published a cover story about the “hidden epidemic” of abuse, to which half a million children – above all, girls – fall victim every year.

The Spiegel refers to crime statistics, according to which over 12,000 children (85% of which are girls) were victims of sexual abuse in 1981. A “huge number of unreported criminal cases” must be added to this figure because experts estimate that only every one in every ten to 20 cases is reported. “That means that, estimated conservatively, about 150,000 children fall victim to sexual violence each year.”

Spiegel-author Valeska von Roques covers an event organised by Wildwasser at the Technische Universität in Berlin, at which victims talk publicly about their experiences of abuse. More and more victims break their silence.

In August 1984, the ARD broadcasts Das schreckliche Geheimnis – Sexueller Missbrauch in der Familie. The film’s writer Sabine Zurmühl – formerly one of the founders of the feminist magazine Courage – is able to shoot the documentary thanks to the support of Wildwasser.

9 March 1985: Green Party Calls for Abolition of § 176

At their party conference, Green Party members from North Rhine-Westphalia adopt an election programme that calls for the abolition of §176. “Consensual sexuality is a form of communication between people of all ages (…)”, the programme states, and “non-violent sexuality should never be the subject of criminal prosecution. Therefore, all criminal offences are to be abolished that threaten non-violent sexuality with punishment.” The fact that sex between adults and children is per se violent due to the inherent power imbalance is ignored in the resolution.

![Zart war ich, bitter war’s : Handbuch gegen sexuellen Missbrauch (2001). - Enders, Ursula [Hrsg.]. Köln : Kiepenheuer & Witsch (FMT-Signatur: SE.05.NA.004). Zart war ich, bitter war’s : Handbuch gegen sexuellen Missbrauch (2001). - Enders, Ursula [Hrsg.]. Köln : Kiepenheuer & Witsch (FMT-shelfmark: SE.05.NA.004).](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/SE.05.NA_.004-186x300.jpg)

1987: The Association Zartbitter

The society Zartbitter is set up in Cologne. The founders initially want to establish a network for specialists and develop sex abuse prevention programmes. However, when the media publishes the date of the specialists’ meeting, it is predominantly victims of abuse seeking support who attend: “19 affected women squeezed into the relatively small room. The news coverage had encouraged them to set out. The brave women had voted with their feet: from this day onwards, Zartbitter also saw itself as a contact point and information centre for those affected by abuse.” Zartbitter, and in particular its founder Ursula Enders, became an important voice in the fight against sexual abuse. Three years after its foundation, the counselling centre publishes the handbook Zart war ich, bitter war‘s14, which quickly becomes a classic.

What Happens Next?

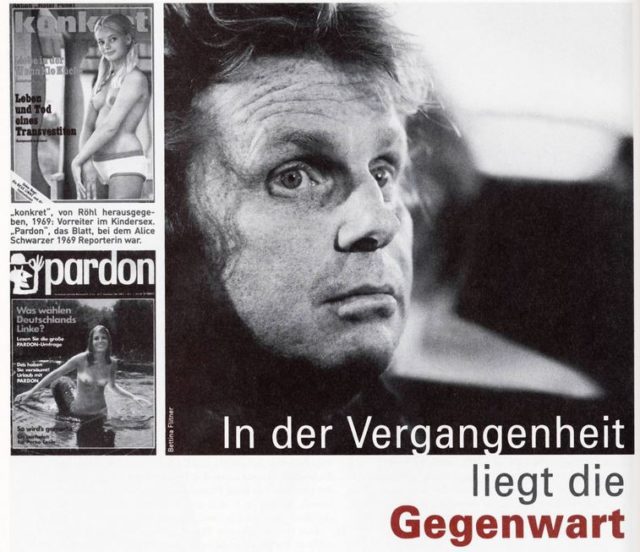

After the women’s movement was successful in breaking the silence about sexual abuse, or rather in making it clear to the public that this ‘trivial offence’ is actually a very serious crime, the ‘backlash’ follows at the beginning of the 1990s: the catchphrase ‘Missbrauch des Missbrauchs’, ‘misuse of sex abuse’ makes the rounds. The general tenor: the epidemic of sex abuse is a myth maintained by hysterical feminists who see sexual assault everywhere, even where there isn’t any. Champions of the Missbrauch des Missbrauchs slogan are the teachers Katharina Rutschky and Prof. Reinhart Wolff. At the end of the 1980s, Wolff had developed a strategy called ‘Hilfe statt Strafe’ at the behest of the Deutscher Kinderschutzbund that – with its “family-orientated approach” – does not separate offenders from their victims.15 In 1992, Rutschky publishes Erregte Aufklärung with the left-wing konkret-Verlag, in which she insinuates that feminists who denounce sex abuse are guilty of “delusion” and “dogmatic misogyny”.16 The book is widely and well received – also by reputable media outlets – as a “clever contribution” (FAZ).17 There is mention of “abuse myths” and “hysteria about unreported cases”.

In May 1993, EMMA publishes an article,

uncovering the well-oiled network of paedosexual ‘friendly’ experts, lawyers, scientists, and organisations, such as the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Humane Sexualität (AHS). Even the head of the Deutscher Kinderschutzbund Walter Bärsch is clearly embroiled in this network. Despite its explosive power, the article is ignored by other media outlets. In fact, media interest is only roused when in 2013 – 20 years later! – the Göttingen professor Franz Walter examines the role played by the Green Party in trivialising sex abuse and comes across the same networks over the course of his investigation.

Two trials that take place in 1993 demonstrate how much opinions have shifted as a result of the Missbrauch des Missbrauchs campaign: the trial of an educator at a daycare centre in Coesfeld and the so-called Wormser Prozesse. Although the court proceedings in both these cases start with clear statements by the children as well as medical reports, all defendants are acquitted. In both cases, expert witnesses are able to undermine the children’s credibility and to denounce the Wildwasser employees who had questioned the children as ideologically blinded feminists. According to these experts, the Wildwasser employees had planted the idea in the children’s heads that they were abused.

The court reporters Gerhard Mauz and Gisele Friedrichsen, both working for the Spiegel, play a decisive role in the turnaround of the trials. They characterise the doctors who had diagnosed the children’s injuries as “witch hunters” and consider the therapist from Wildwasser in Worms to be guilty of “amateur investigative zeal”. In the following years, the duo Mauz/Friedrichsen attract attention for their baised coverage in favour of suspected offenders in abuse trials. The Missbrauch des Missbrauchs campaign’s attempt to intimidate victims and their potential helpers is successful.

On 17 November 1999, the article Der Lack ist ab is published in the Frankfurter Rundschau. Its author Jörg Schindler describes how Gerold Becker – headmaster of the Odenwaldschule in Hessen from 1972 to 1985 – had regularly sexually abused several pupils. Two of them had taken their story to various newspapers when Becker resumed work at the school in 1998. Only the Frankfurter Rundschau and EMMA cover the scandal; the others refuse. There fails to be a reaction. In fact, there continues to be collective silence about the fact that sex abuse was systemic at the ‘progressive education’ school which is considered a left-wing flagship project.

In March 2001, Alice Schwarzer writes the articleIn der Vergangenheit liegt die Gegenwart about Daniel Cohn-Bendit. ‘Dany le Rouge’ – a Member of European Parliament for the Greens – had written about his two-year stint, between 1972 and 1974, as a kindergarten teacher in his autobiography Der große Basar. Cohn-Bendit recounted how his “constant flirtation with the children soon assumed erotic characteristics.” “I could really sense how little girls of five had already learned to turn me on.” And how “more than once, several children opened my fly and began to stroke me.” Then, “because they insisted”, he also stroked them.

When these quotes are publicly debated at the beginning of the 2000s, Cohn-Bendit claims that this part of his life story is nothing more than a fiction. Schwarzer accuses Cohn-Bendit of never distancing himself from his former behaviour, from this zeitgeist: “I expect him not to again talk his way out of it, but to take responsibility for what he has thought, done, and preached.”18 Cohn-Bendit never replied to his old political ally. It was not until 2013 when criticism of his behaviour resurfaced that Cohn-Bendit began to speak self-critically about his earlier endorsement of paedophilia.

In January 2010, it becomes public knowledge that pupils at the Catholic Canisius-Kolleg in Berlin were regularly sexually abused by priests. This case is the first of many announcements about a wave of abuse cases at Catholic schools. Women and men who had been abused in (church) homes speak out. Sex abuse is discussed in all the talk shows, and the government comes under pressure. The CDU/FDP coalition sets up a roundtable, at which also the Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Feministischer Organisationen gegen Sexuelle Gewalt an Frauen und Mädchen (BAG Forsa) is represented.

The government commissions the former Minister for Women Christine Bergmann (SPD) with the review of sexual abuse not only in the Catholic Church, but everywhere: in families, schools, societies, and other institutions. The Unabhängige Beauftragte für Fragen des sexuellen Kindesmissbrauchs or ‘independent commissioner for the review of child sex abuse’ – as Bergmann’s role is officially called – sets up a hotline for those affected. Over 11,000 ring up; the youngest is six, the oldest 89. Bergmann, who also conducts interviews with counselling centres and therapists, ultimately presents the government with a catalogue of demands. The catalogue is a landmark document. The demands that victims of abuse and feminist counselling centres have made for decades are for the first time taken up at an official level.

In this sensitised climate, the systemic abuse at the Odenwaldschule by the headmaster Gerold Becker and other teachers now receives a public response. The egregious role played by not only the Green Party, but also the FDP and the left-wing and liberal media (from the taz to the Zeit) in the trivialisation of sexual abuse is thematised. The Greens commission the Göttingen professor Franz Walter to undertake a review of their history. Walter’s findings as well as the callous conduct of officials like Jürgen Trittin or Volker Beck cost the Green Party votes – and several percentage points – in the 2013 elections.

The extent of sexual abuse in families and institutions as well as the traumatic consequences for victims is publicly recognised today. Over the course of the abuse debate since 2010 and after the roundtable’s final report, a Fonds Sexueller Missbrauch is set up from which victims of sexual abuse can receive payments – e.g., for the cost of therapy. The government has paid 50 million euros into the fund; of the German federal states, only two of 16 have made a contribution so far (Bavaria and Mecklenburg-West Pomerania).

The Unabhängige Beauftragte für Fragen des sexuellen Kindesmissbrauchs has been working since May 2015 with a Betroffenenrat, ‘council of victims’ comprising 15 members; they regularly go public with criticism and demands. For example, there are still too few treatment options for abuse victims. Further, the number of court proceedings that are discontinued is still too high for abuse trials, and the verdicts that are typically handed down are at the lower end of the sentencing range.

Nowadays, there is a large network of support services for the victims of sexual abuse: Wildwasser lists 176 counselling centres in Germany. However, these are chronically underfunded and are therefore only able to offer limited assistance.

References

1 Stüben, Olaf (1979): Pädophilie : Verbrechen ohne Opfer. - In: taz, 16.11.1979, see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen und Jungen : Pädophilie-Debatte / Strafrechtsdebatten (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.05.01).

2 Merer, Peter (1980): Kinderschänder?. - In: taz, 07.02.1980, see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen und Jungen : Pädophilie-Debatte / Strafrechtsdebatten (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.05.01).

3 Hartleb, Peter (1980): Wegen Zärtlichkeit im Knast. - In: taz, 14.02.1980, see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen und Jungen : Pädophilie-Debatte / Strafrechtsdebatten (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.05.01).

4 Rush, Florence (1980): The best kept secret: sexual abuse of children. - New Jersey : Prentice Hall (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.05.004-1980).

5 Rush, Florence (1984): Das bestgehütete Geheimnis : sexueller Kindesmißbrauch. 2. Aufl. - Berlin : Sub-Rosa-Frauenverl., p. 26 (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.05.004-1984).

6 See Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen und Jungen : Pädophilie-Debatte / Strafrechtsdebatten (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.05.01).

7 Die Mädchenhäuser (1996). - In: EMMA, Nr. 6, pp. 34-37. - Retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/45352 or FMT Shelf Mark: Z-Ü107:1996-6-a.

8 Oktober 1983 ist das Datum der Eintragung ins Vereinsregister. See also Vom Tabu zur Schlagzeile : 30 Jahre Arbeit gegen sexuelle Gewalt – viel erreicht?! ; Kongressdokumentation. - Wildwasser e.V. [Hrsg.], p. 24. - Retrieved from: www.wildwasser-berlin.de/tl_files/wildwasser/Dokumente/2014/Dokumentation_30-Jahre-Wildwasser-eV-Berlin.pdf [PDF-Document].

9 Wildwasser : Arbeitsgemeinschaft gegen sexuellen Mißbrauch von Mädchen. - [Informationsblatt zur Gründung von Wildwasser und Aufruf zur Materialsammlung und Mitarbeit, undatiert], see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen und Jungen : Feministische Selbsthilfe, Kapitel Wildwasser (FMT Shelf Mark PD-SE.05.08).

10 Kavemann, Barbara ; Lohstöter, Ingrid (1984): Väter als Täter : sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen ; "Erinnerungen sind wie eine Zeitbombe". Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.05.05).

11 Kavemann, Barbara ; Lohstöter, Ingrid (1985): Plädoyer für das Recht von Mädchen auf sexuelle Selbstbestimmung. - In: Sexualität : Unterdrückung statt Entfaltung. - Sachverständigenkommission Sechster Jugendbericht [Hrsg.]. Opladen : Leske Verlag + Budrich GmbH, p. 89 (FMT Shelf Mark: LE.03.160).

12 von Roques, Valeska (1984): Wenn du was sagst, bring ich dich um. - In: Spiegel, Nr. 29, 16.7.1984, Retrieved from: www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-13509043.html and see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen : Inzest. (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.05.02).

13 Sexual Abuse - The Growing Outcry Over Child Molesting (1984). - In: Newsweek, 14.05.1984, see Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen : Inzest (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.05.02).

14 Zart war ich, bitter war’s : Handbuch gegen sexuellen Missbrauch (2001). - Enders, Ursula [Hrsg.]. Köln : Kiepenheuer & Witsch (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.05.NA.004).

15 See Deutscher Kinderschutzbund - Landesverband Hamburg. Die Lobby für Kinder: Arbeitsweisen. - Retrieved from: www.kinderschutzbund-hamburg.de/arbeitsweisen.html

16 Rutschky, Katharina (1992): Erregte Aufklärung : Kindesmißbrauch: Fakten & Fiktionen. - Hamburg : Klein. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.05.077).

17 See Pressedokumentation: Sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.05.04).

18 Alice Schwarzer (2001): In der Vergangenheit liegt die Gegenwart. - In: EMMA, Nr. 3, p. 23 (FMT Shelf Mark Z-Ü107:2001-3-a).

All internet links were last accessed on 05.03.2018.

Selective Bibliography

Documents online

Recommendations

Kavemann, Barbara ; Lohstöter, Ingrid (1984): Väter als Täter : sexuelle Gewalt gegen Mädchen ;

"Erinnerungen sind wie eine Zeitbombe". - Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.05.005).

Rush, Florence (1984): Das bestgehütete Geheimnis : sexueller Kindesmißbrauch. - Bartoszko,

Alexandra [Hrsg.] - Berlin : Sub-Rosa-Frauenverl. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.05.004-1984).

Zart war ich, bitter war's. Handbuch gegen sexuellen Missbrauch (2001). - Enders, Ursula [Hrsg.]. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2001 (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.05.NA.004).

FMT Press Documentation

Press Documentation on Sexual Abuse: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Selected FMT-Sources (lists)

FMT literature selection Sexual Abuse: PDF-Download

EMMA article Sexual Abuse: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Women's Refuges - Protection from (Sexual) Violence

Women's Refuges - Protection from (Sexual) Violence

Beginning in the mid-70s, the women’s movement made the dramatic extent of violence by men against their own wives and children public and launched the first women’s refuges. › mehr

Fighting Sexual Violence and (Marital) Rape

Fighting Sexual Violence and (Marital) Rape

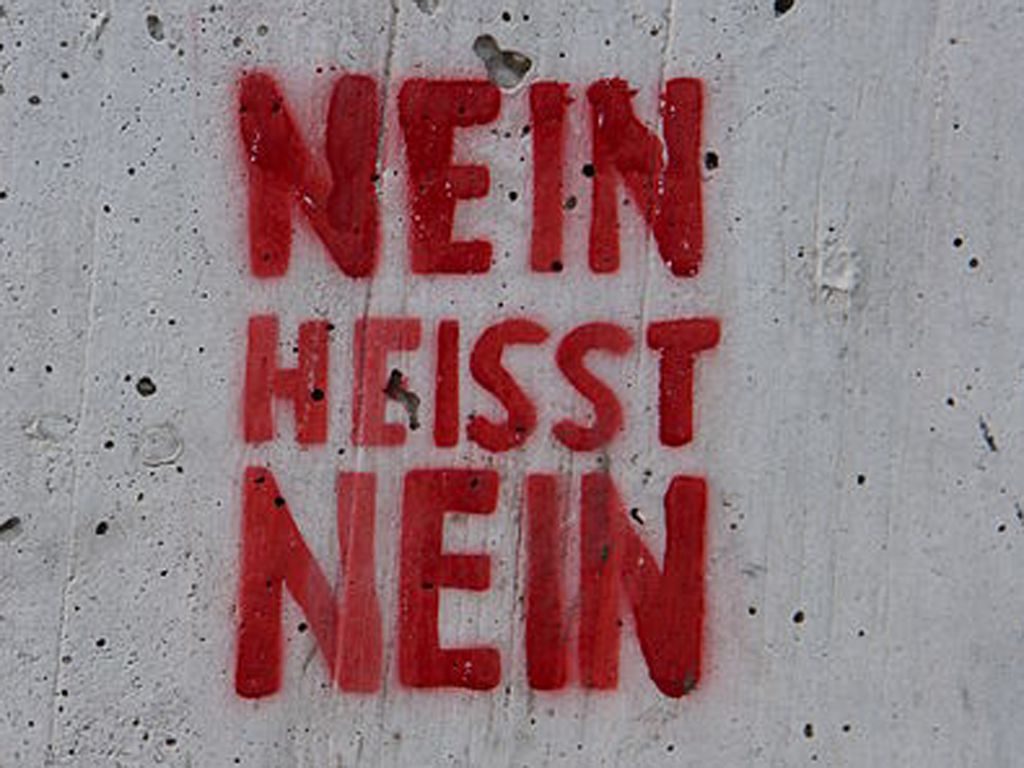

In the mid-1970s, the women’s movement brought the epidemic of sexual violence to the public’s attention. The women fought for a sex crime law reform, that finally came through 1997 and 2016. In Germany today the principle rules: No means No. › mehr

Sexual Harassment - the Long Way to Sex Crime Legislation

Sexual Harassment - the Long Way to Sex Crime Legislation

Sexual harassment in the workplace became a public issue in Germany in the late 1970s, studies and debates have followed until it finally became a part of the sex crime legislation. › mehr