When the women’s movement started, housework was still by law a woman’s job. According to German civil code, a married woman was only allowed to work if she didn’t neglect her “domestic duties”. Feminists fought successfully for the abolition of this law, and they are the first to point out the financial value of the housework that housewives carry out for free.

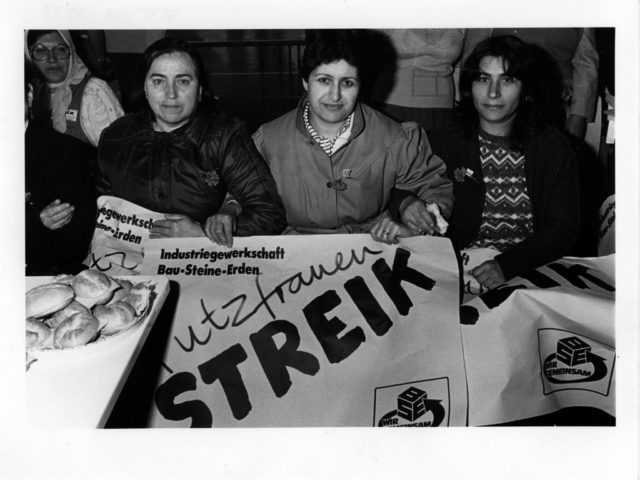

Soon thereafter, the inferior pay of working women became a key issue, and in 1981 the Heinze-Frauen win a first, if only partial, victory in the fight for ‘equal pay for equal work’ with their legendary strike. The lifting of the ban on night work – which above all served as a pretext to keep women away from well-paid men’s jobs – was also controversially called for by the women’s movement. In general, the women’s movement called for protest against unions and so-called ‘male professions’. Feminists demanded: „Half of the world for women, half of the home for men!“ This was the beginning of the discussion about work-life balance that is still in full swing today.

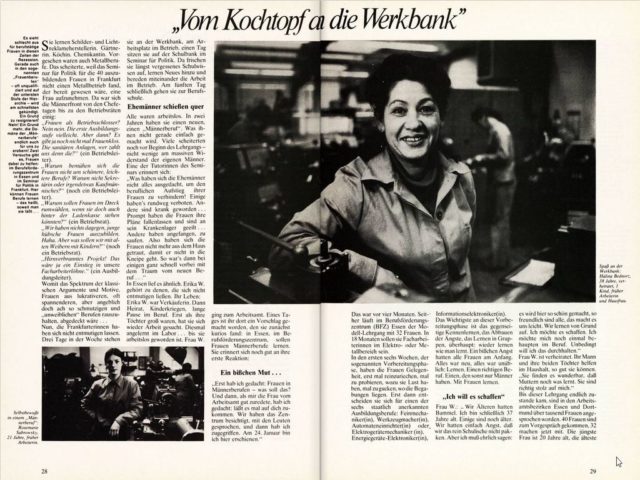

1973: Housework is Mostly Women’s Work

![Frauenarbeit - Frauenbefreiung : Praxis-Beispiele und Analysen (1973). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. 1. Aufl. - Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp (FMT-Signatur: AR.07.040-1973). Frauenarbeit - Frauenbefreiung : Praxis-Beispiele und Analysen (1973). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. 1. Aufl. - Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp (FMT-Signatur: AR.07.040-1973).](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Schwarzer_Frauenarbeit_Frauenbefreiung-e1530270482391-418x640.jpg)

In The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community – published in Italy in 1972 and in Germany in 1973 with the series Internationale Marxistische Diskussion – Dalla Costa declares: „With the advent of capitalism, the socialisation of production was organised with the factory as its centre. Those who worked in the new productive centre, the factory, received a wage. Those who were excluded did not. Women, children, and the old lost the relative power that derived from the family’s dependence on their labour, which was seen to be social and necessary.“3 In several countries – including Italy, England, the USA, and finally also Germany – „wages-for-housework“ groups were established and started to campaign.

February 1974: Desperate Housewives?

At a conference, Brigitte presents a study that was launched by the magazine and implemented by the sociology professor Helge Pross. Title: Die Wirklichkeit der Hausfrau. Die erste repräsentative Untersuchung über nichterwerbstätige Ehefrauen: Wie leben sie? Wie denken sie? Wie sehen sie sich selbst?4 On the surface, the results of this study suggested that „housewives are satisfied with their lives.“ However, on closer examination, there was cause to doubt this conclusion: for example, 40% of the 1,200 housewives surveyed would rather have taken up employment. And as for the respondents who claimed they did not want to get a job, the question arose as to why: that the woman would continue to be responsible for housekeeping and child-rearing despite employment was virtually self-evident at this time. It became clear that many women who refused employment had done so due to opposition from their husbands and children and fear of the imminent double burden.

September 1974: Debate on Wages for Housework

Alice Schwarzer publishes an opinion piece entitled Nehmt euch in acht vor dem Hausfrauenlohn! in the magazine Pardon. She warns: „Women’s status as slaves will not only stay the same irrespective of these handouts disguised as wages, but men’s convenience will also once again be institutionalised. The housewives’ wage would only be an obstacle at a time when women are finally starting to break out from the isolation of the ‘female sphere’ into the male-dominated ‘outside world’.“ Schwarzer argues for the employment of women, since only a job can make women economically independent from their husbands and, moreover, put an end to domestic isolation. According to Schwarzer, to prevent working women from collapsing under the strain of the double burden, women would have to demand equal division of the housework from men.5

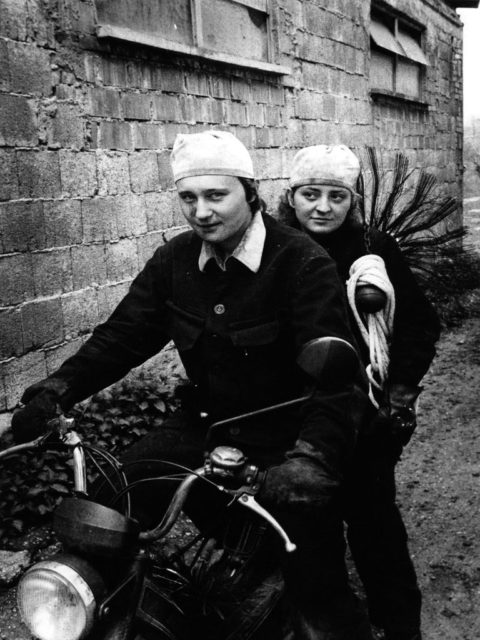

May 1975: Call for Lifting the Ban on Night Work for Women

The Bundesfrauenausschuss der Deutschen Postgewerkschaft calls for the lifting of the ban on night work for women.6 The ban dates back to working time regulations from 1891 that prohibit women from working between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. and, in multi-shift operations, between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m. The rationale: „In addition to considerations of moral decency, it is important to do justice to the peculiarities of the female organism and the social position of women as mother and housewife.“7

However, the ban only affects female blue-collar workers and not female white-collar workers, so that night work by women in care homes, in hospitals, in catering, or indeed for the postal service had long been common. The Frauenausschuss der Postgewerkschaft is at odds with the Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (DGB) over the demand; the latter is against the extension of night work for women.

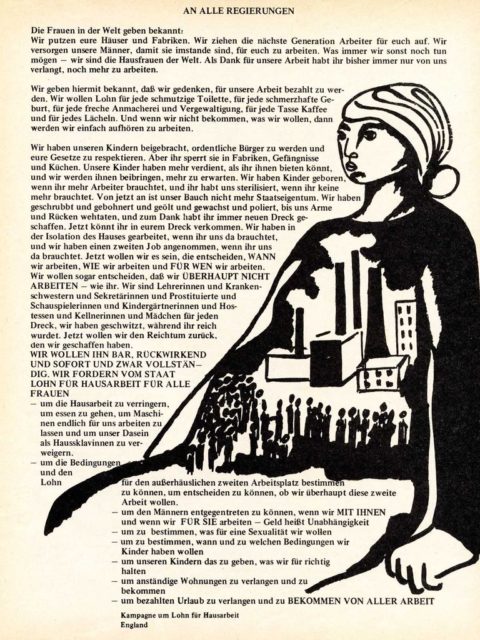

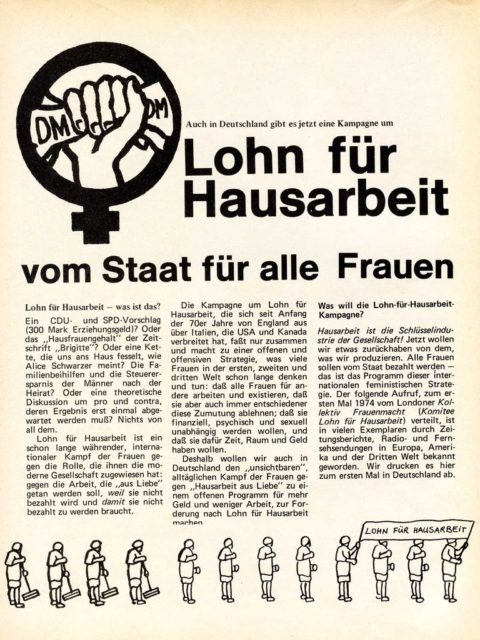

May 1977: Campaign Lohn für Hausarbeit

The campaign manifesto for Lohn für Hausarbeit in the run-up to 1 May 1977 states: „To all governments we hereby declare that we intend to be paid for our work. We want a wage for every dirty toilet, for every painful birth, for every brazen proposition and rape, for every cup of coffee, and for every smile. And if we don’t get what we want, then we’ll simply stop working!“8 The appeal comes from the London collective Wages for Housework, which spreads the message internationally.

In Germany, Courage publishes the manifesto in their 15 March 1977 issue. In its February issue, Courage had already argued in favour of a wage for housework in an open letter to Alice Schwarzer: „Housework doesn’t stay housework if it is paid. Housework is thus no longer invisible – neither the ‘love’, nor the ‘nature’, nor the ‘destiny’ of women. Only then can a man decide whether he wants to do housework; only then can it be reduced; and only then can this hapless ‘labour of love’ disappear from the scene.“9

While the feminist magazine Courage backs the Lohn für Hausarbeit campaign in Germany, EMMA is a staunch opponent of housewives’ wages: „[This] pocket money would only thinly gild women’s fate in a man’s society, in which the role of housewife is not a free choice but enforced and reserved exclusively for women. (…) Housewives’ wages wouldn’t liberate women, but rather enslave them further! Would chain them even more to the kitchen sink!“10

1 July 1977: Reform of German Family Law

The reform of family law comes into force. Central demands of the women’s movement have found their way into the new legislation enacted by the SPD/FDP coalition. Thus, housekeeping is now no longer legally the women’s responsibility. The new § 1356 BGB reads: „Spouses settle matters of housekeeping by mutual agreement.“

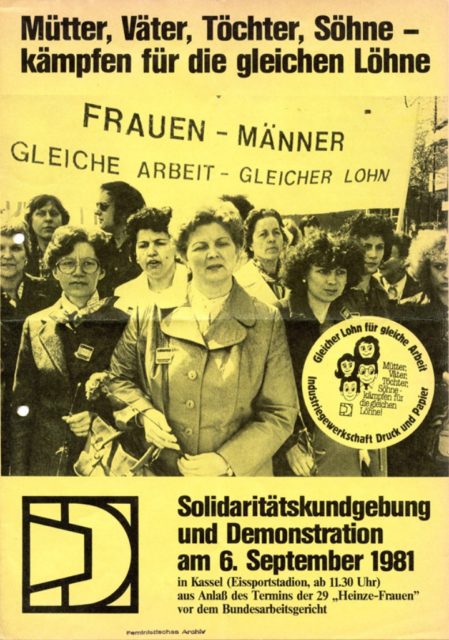

10 May 1979: Heinze-Frauen battle for Equal Pay

The so-called Heinze-Frauen win their case for equal pay for equal work before an industrial tribunal in Gelsenkirchen. 29 female employees from the film development department of the Gelsenkirchen-based photo company Heinze had taken legal action to receive the same wages as their male colleagues. The company justified the additional allowance for male employees with the fact that for the hourly wage of 6 D-Mark they wouldn’t be able to find any men willing to take the job, and male employees were necessary because only they could do night work in the photo lab due to the ban on night work for women.

The women justify their claim for equal pay with Art. 3 of Basic Law: „Men and women are equal.“ After the Heinze company lodged an appeal, the final verdict is at long last reached by the Federal Labour Court on 6 September 1981: the pay difference between women and men violates the principal of equality. (A documentary report about the struggle of the Heinze-Frauen is published in 1982 as a book entitled Wir wollen gleiche Löhne!11)

The lawsuit brought by the Heinze-Frauen causes a stir nationwide, and many solidarity campaigns were launched. After the plaintiffs’ victory, which set a precedent, there is a spate of lawsuits by women seeking equal pay.

14 August 1980: Anti-Discrimination Policy

An anti-discrimination policy that prohibits discrimination of employees on the basis of gender is introduced into German civil code. § 611a now reads: „An employer may not discriminate against an employee on grounds of sex under any agreement or measure, in particular when initiating the contractual relationship, in connection with promotion, when giving instructions and in connection with dismissal.“ The burden of proof lies with the employer.

January 1982: Hearing on Anti-Discrimination Law

The federal government organises a hearing on a planned anti-discrimination law, at which the ban on night work for women is also discussed. In a statement about the hearing, EMMA calls for the abolition of the ban on night work. The Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund still voices its opposition to night work for women. The reasoning: although night work is proven to be equally detrimental to the health of both sexes, women are „usually unable to get enough sleep during the day due to the fact that they are typically chiefly responsible for domestic tasks.“

In the article Gefährlicher Schutz, EMMA criticises this attitude as „a polite euphemism for Hausarbeitszwang, housework imposed and enforced by the patriarchy.“12 EMMA declares the ban on night work for the alleged protection of women to be bigoted because hundreds of thousands of working women already practice their professions at night. At the same time, the ban on night work for women has significant disadvantages for female workers: companies with night-time shifts either outright refuse to train female apprentices or do not offer them permanent employment on completion of their apprenticeships. Furthermore, women are excluded from often well-paid night work positions. Conclusion: „Because […] this ‘protection’ from night work is de facto just another excuse to discriminate against women, it would be more honest to finally abolish this special ban on women’s night work! And at the same time to launch a resolute fight against night work in general. For women and men alike.“13

The Federal Constitutional Court still considers the ban on night work for women to be justified on account of their „weaker constitution“.14 The 1987 census shows that 1.3 million women carry out permanent, regular, or occasional night work.

What happens next? No More Night-Ban, Equal Pay Day and Call for More Transparency

In 1988, the Federal Constitutional Court declares so-called Leichtlohngruppen [‘low-wage groups’] to be unlawful. As early as 1955, the Federal Constitutional Court had declared it unconstitutional to pay women lower wages than men on the basis of gender alone. In response, employers adjusted their wages according to leicht, „light“ and schwer, „heavy“ work, with the work carried out by women almost always defined as „light“. The Leichtlohngruppen therefore consisted exclusively of women. The Federal Labour Court recognises this practice as „indirect discrimination“ of women. The verdict was secured by female metalworkers from a cable company in Witten. The Federal Labour Court states in its verdict that „heavy physical work means work that involves standing, rhythmic and repetitive actions, nervous strain, or noise pollution“.15

With German reunification in 1990, the ban on night work in the FRG now also applies to women from the former GDR. Layoffs are the consequence.

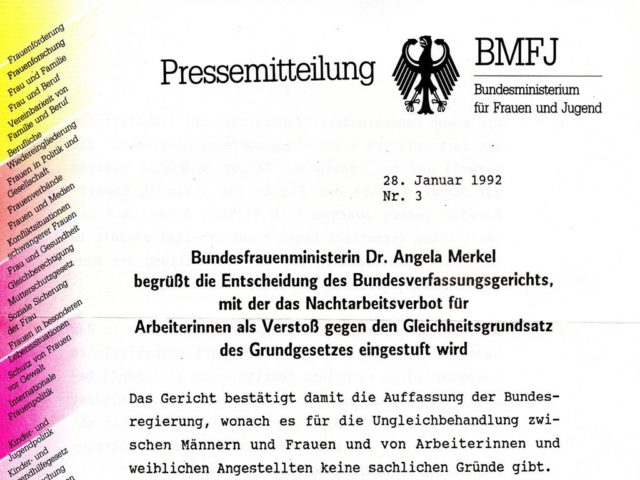

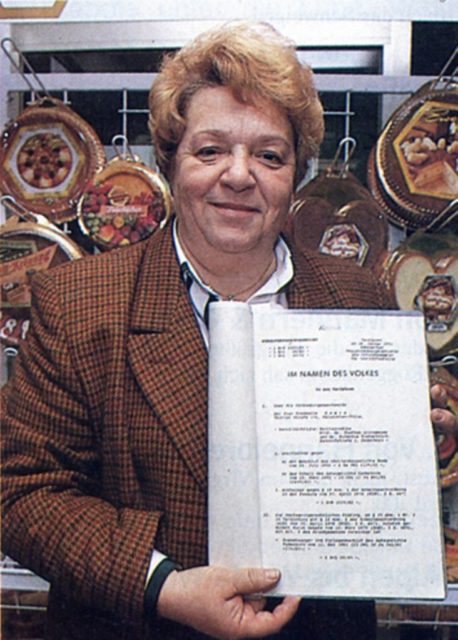

On 28 January 1992, the Federal Constitutional Court declares the ban on night work for women to be unconstitutional.16 The bread manufacturer Rosemarie Ewers filed a lawsuit against the ban. The medium-sized business owner had received several fines because she had employed women to work nights in her bakery. Ewers had argued that she depended on female employees because only they were willing to work part-time. The Federal Constitutional Court rules: „The ban on night work for female workers violates Art. 3 III GG.“17 The judges in Karlsruhe don’t accept the two main arguments against night work by women and thus concur with the argumentation brought by the Deutscher Juristinnenbund, which also opposed a ban on night work for women.

Argument 1. Night work puts an additional burden on women because they are also responsible for housekeeping and child-rearing during the day.

The court declares: „The added burden of housework and child care is not sufficiently gender-specific. It is, however, consistent with traditional gender roles that the woman keeps house and cares for the children, and it cannot be denied that this role very often falls to the woman even if she is employed like her male partner. But this Doppelbelastung [‘double burden’] only affects women with dependent children at full force when they are single, or the male partner leaves the child care and the housework solely to the woman despite her night work.“18

Argument 2. Women are at particular risk on their nightly journey to and from their place of work.

The court declares: „This is certainly true in many cases. But even this does not justify barring all female workers from night work. The state cannot elude its responsibility of protecting women from assault on public streets in that it prevents them from leaving their homes at night by restricting their occupational freedom.“19

And finally, the court argues: „Women are thus disadvantaged in their job search. They cannot take on work that has, at least partially, to be carried out at night. In some industries, this has led to a significant decline in the apprenticeship and employment of female workers. Furthermore, female workers are prevented from freely disposing of their work hours. They are not able to earn night bonuses. All of this can have the consequence that women continue to be encumbered to a much greater extent than men by the child care and housework they perform alongside a professional career, which in turn consolidates traditional gender roles. In this respect, the ban on night work for women makes it difficult to reduce social disadvantages for women.“20

The Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz (AGG) comes into force in 2006. The so-called „anti-discrimination law“ in § 2 prohibits the unequal payment of men and women on the basis of gender: „Discrimination is inadmissible with regard to employment and working conditions, including pay.“21

Equal Pay Day – instigated in 1996 by the American National Commitee for Pay Equity – has been celebrated in Germany since 15 April 2008. Women protest against the so-called “gender pay gap”, i.e. the percentage difference between men and women’s hourly earnings; in Germany, men earn on average 22% more than women. But direct wage discrimination is only one reason for the gender pay gap. The pay gap is also a consequence of the fact that more women work part-time and in lower paid „female professions“. This protest marks the day to which women must work in order to earn the same amount as men earned in the previous year. The women’s network Business Professional Women – backed financially by the Ministry for Women’s Affairs – brought the Equal Pay Day to Germany. Since then, it has taken place on the third Saturday in March. The protest’s symbol is a red bag.

In September 2013, the industrial tribunal in Koblenz rules in favour of a female employee at the Birkenstock company, who had taken the shoe company to court in order to receive the same pay as her male colleagues. At a company meeting in the autumn of 2012, the employee had discovered that she and her female colleagues had for decades received approximately €1 less hourly pay than their male colleagues. The employment appeals tribunal in Mainz upholds the verdict and declares the actions of the shoe maker in paying the women less on the basis of their gender to be „blatently unlawful“. The verdict is one of the few exisiting judicial rulings against pay discrimination; it usually cannot be proven due to a lack of pay transparency.22

The Minister for Women Manuela Schwesig (SPD) presents a draft for an Entgeltgleichheitsgesetz [‘equal pay law’] in December 2015. According to the bill, companies are to make their wages and salaries transparent, so that their employees can check if they are being paid less on the basis of gender alone. „With more transparency, we want to ensure that wage differences can no longer be concealed“, the minister declares.23 After protests by employers’ associations, the bill is watered down: the obligation to provide information is only to apply to companies with more than 500 employees. The Deutscher Juristinnenbund criticises the „voluntary“ and non-certified testing procedure. Their conclusion: „Since the draft legislation only partially creates more opacity and has the potential to promote behaviour that only simulates a lack of discrimination, it may detract from the matter of equal pay for women and men.“

References

1 Frauenarbeit - Frauenbefreiung : Praxis-Beispiele und Analysen (1973). - Schwarzer, Alice [ed.]. 1. Edition. - Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.040-1973).

2 Women's liberation : Frauen gemeinsam sind stark! ; Texte und Materialien aus der neuen amerikanischen Frauenbewegung (1972). - Becker, Barbara [ed.] ; Kramer, Helgard [ed.] ;

Kiderlen, Elisabeth [ed.] ; Krechel, Ursula [ed.] ; Margit, Mayer [ed.] ; Schoen, Barbara [ed.]. Frankfurt am Main : Roter Stern, p. 10. (Shelf Mark edition of 1977: FE.04.NA.002)

3 Dalla Costa, Mariarosa ; James, Selma (1973): Die Macht der Frauen und der Umsturz der Gesellschaft. - Berlin : Merve-Verl. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.019). Retrieved from: http://www.fau-mannheim.de/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/dallacostadiefrauenundderumsturzdergesellschaft.pdf

4 Pross, Helge (1976): Die Wirklichkeit der Hausfrau : die erste repräsentative Untersuchung über nichterwerbstätige Ehefrauen ; wie leben sie? ; Wie denken sie? ; Wie sehen sie sich selbst?.

Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.025), siehe auch Pressedokumentation: Unbezahlte Arbeit: Hausfrauen, Hausarbeit (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-AR.03.01, Kapitel 5 und 6).

5 Schwarzer, Alice (1974): Nehmt Euch in acht vor dem Hausfrauenlohn! : Die verhängnisvollen Folgen eines angeblichen Ausweges. - In: Pardon, no. 9, pp. 26 - 27 (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07-a, Obj. Nr. 72477).

6 Interview mit Ingridlotte Richter: Nachtarbeit für Frauen verbieten? (1980). - In: Stern, no. 9, p. 200, see Pressedokumentation: Frauenarbeitsschutz 1962-1992 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-ST. 13.16, Kapitel 3).

7 Slupik, Vera (1982): Gefährlicher Schutz. - In: EMMA, no. 5, p. 28.

8 Lohn für Hausarbeit (1977). - In: Courage, no. 3, pp. 16 - 17.

9 Lohn für Hausarbeit : offener Brief an Alice (1977). - In: Courage, Nr. 8, p. 38 - 40 (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-Ü104:1977-8-a). Retrieved from: library.fes.de/cgi-bin/courage.pl

10 Schwarzer, Alice (1977): Hausfrauenlohn?. - In: EMMA, no. 5, p. 3. and see https://frauenmediaturm.de/neue-frauenbewegung/chronik-1974

11 Wir wollen gleiche Löhne! : Dokumentation zum Kampf der 29 "Heinze"-Frauen (1980). - Kaiser, Marianne [ed.]. Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.10.013).

12 Slupik, Vera (1982): Gefährlicher Schutz. - In: EMMA, no. 5, p. 28.

13 Ibid, p. 30.

14 Pfarr, Heide (1992): Auf Nachtarbeit folgt für Mütter die zweite Schicht im Haushalt. - In: Frankfurter Rundschau, no. 107, 08.05.1992, p. 15, see Pressedokumentation: Frauenarbeitsschutz 1962-1992 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-ST.13.16, Kapitel 3).

15 DGB (2013): Gleiches Geld für gleichwertige Arbeit , 10.10.2013. - Retrieved from: frauen.dgb.de/++co++54aeb962-31c0-11e3-8336-00188b4dc422/

16 Bastion der Männer (1992). - In: Der Spiegel , no. 6, 03.02.1992. Retrieved from: www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-13686238.html

17 Windthorst, Kay (ed.): Zum BVerfG - Nachtarbeitsverbot für Arbeiterinnen. Retrieved from: esolde.uni-bayreuth.de/entscheidungen/350-grundrechte/einzelne-grundrechte/gleichheitsgrundrechte/spezielle/art-3-abs-3-gg/144-bverfg-nachtarbeitsverbot-fuer-arbeiterinnen

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Die aktuelle Fassung des Allgemeine Gleichbehandlungsgesetzes (AGG). Retreived from: www.gesetze-im-internet.de/agg/BJNR189710006.html

22 Koschnitzke, Lukas (2015): Ungleicher Stundenlohn : Birkenstock zahlte Frauen einen Euro weniger. - In: Der Spiegel, no. 11, 07.03.2015. Retrieved from: www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/unternehmen/birkenstock-frauen-bekamen-weniger-lohn-als-maenner-a-1022162.html

23 Louis, Chantal (2015): Wir wollen mehr Lohn! - In: EMMA, no. 3, p. 44.

Date of the last linkcheck 21.02.2019.

Selective Bibliography

Documents Online

Bursig, Beatrix (1992): „Ohne Frauen geht es nicht“. - In: Die Zeit, 17.04.1992.

„Bastion der Männer“(1992). - In: Der Spiegel, no. 6, 03.02.1992.

Recommendations

Frauenarbeit – Frauenbefreiung : Praxis-Beispiele und Analysen (1973). - Schwarzer, Alice [ed.]. Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.040-1973).

Pross, Helge (1976): Die Wirklichkeit der Hausfrau : die erste repräsentative Untersuchung über nichterwerbstätige Ehefrauen ; wie leben sie? ; Wie denken sie? ; Wie sehen sie sich selbst?. - Reinbek bei Hamburg : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verl. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.025).

Weltmarkt Privathaushalt : bezahlte Haushaltsarbeit im globalen Wandel (2002). - Gather, Claudia [ed.] ; Geissler, Birgit [ed.] ; Rerrich, Maria S. [ed.]. - Münster : Westfälisches Dampfboot (Forum Frauenforschung ; 15) (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.082).

Arbeit : Perspektiven und Diagnosen der Geschlechterforschung (2009). - Aulenbacher, Brigitte [ed.] ; Wetterer, Angelika [ed.]. Münster : Westfälisches Dampfboot (Forum Frauen- und Geschlechterforschung ; 25) (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.01.063).

Allmendinger, Jutta (2010): Verschenkte Potenziale? : Lebensverläufe nicht erwerbstätiger Frauen. - Ebach, Mareike [coop.] ; Hennig, Marina [coop.] ; Stuth, Stefan [coop.]. Frankfurt am Main [i.a.] : Campus-Verl. (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.050).

Slaughter, Anne-Marie (2016): Was noch zu tun ist : damit Frauen und Männer gleichberechtigt leben, arbeiten und Kinder erziehen können. - Köln : Kiepenheuer & Witsch (FMT Shelf Mark: AR.07.096).

FMT Press Documentation (German)

Press Documentation on Housework and Claim for Equal Pay: PDF-Download

Press Documentation on Education: PDF-Download

Press Documentation on professions, career choices and female leaders: PDF-Download

Press Documentation on "Nachtarbeitsverbot": PDF-Download

Press Documentation on Houswork salary debate and unpaid care work: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Related Topics

Motherhood and the Feminine in Patriarchy

Motherhood and the Feminine in Patriarchy

The women’s movement critisized the hypocrisy of patriarchal society with respect to motherhood: in Germany mothers were glorified, but left alone with their workload. Feminists also questioned the dogma that women had to become mothers to be fulfilled. › mehr

Female Makers: Pioneering Feminist Projects in Germany

Female Makers: Pioneering Feminist Projects in Germany

"We claim for an all-women room!" That was the slogan of the autonomous women's projects founded in the beginning of the 1970s. › mehr

Female Filmmakers

Female Filmmakers

Many young female filmmakers are active in the Women's Liberation Movement, addressing feminist issues in a variety of film genres. › mehr

![Flugblatt [o.J.] (siehe Pressedokumentation: PD-AR.07.02) Flugblatt [o.J.] (siehe Pressedokumentation: PD-AR.07.02)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Flugblatt_Kampagne_Lohn_fuer_Hausarbeit-e1530270537504-483x640.jpg)