The struggle for abortion rights sparked the emergence of the Women’s Liberation Movement in West Germany. Since 1871 §218 of German penal code prohibited women from terminating pregnancy, and female sexuality was consequently shaped by the fear of unwanted pregnancy. Women continued to have abortions regardless; however, the legal ban not only criminalised women and doctors, but also frequently placed them in life-threatening danger.

The fight for the ‚Fristenlösung‘ – i.e., for abortion with impunity in the first trimester – and thus also for women’s right to self-determination over their own bodies and lives is therefore not accidentally the catalyst for the widespread women’s movement in West Germany at the beginning of the 1970s (in the German Democatic Republic the ‚Fristenlösung‘ was introduced in 1972 – in order to prevent a women’s movement?). The dispute surrounding the ‚Fristenlösung‘ was to last decades and is still not resolved today.

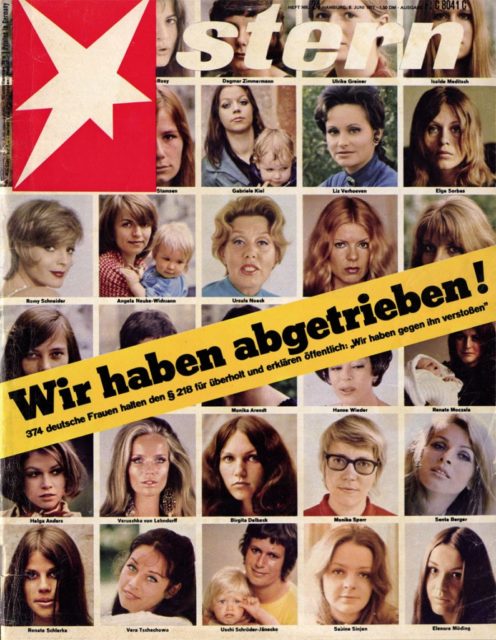

6 June 1971: „We’ve had abortions!“

On the title page of the West German magazine Stern, women disclose: “We’ve had abortions!” Subtitle: “374 German women consider §218 outdated and publicly declare: ‘We have broken the law.’” Among the 374 women who signed the appeal „Ich bin gegen den §218 und für Wunschkinder!“ are prominent figures like Romy Schneider, Senta Berger, and Veruschka von Lehndorff.

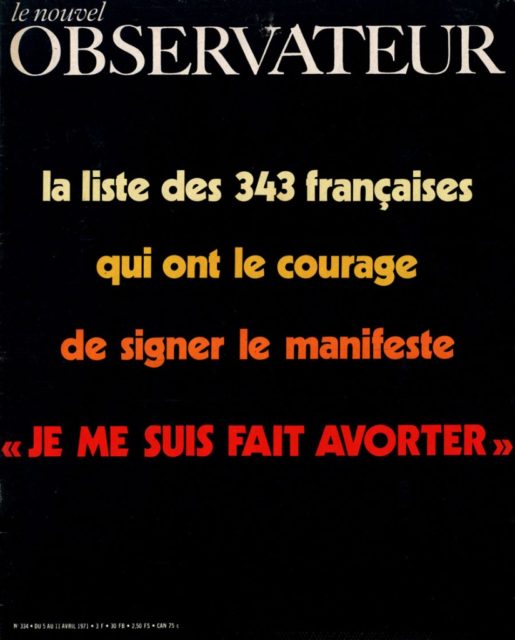

The manifesto was initiated by Alice Schwarzer, who imported the idea from France where the journalist was living and working as a correspondent at the time. On April 5 1971, the French weekly magazine Nouvel Observateur had published the Manifesto of the 343: 343 French women – among them Simone de Beauvoir, Francoise Sagan, and Jeanne Moreau – had declared “Je me suis fait avorter”, or “I’ve had an abortion”. Mastermind of the campaign was the Mouvement de Libération des Femmes (MLF), with whom Alice Schwarzer also collaborated.

For the German self-incrimination campaign, Schwarzer wins the support of the Stern as publisher and of a number of women’s groups, including the Sozialistischer Frauenbund Berlin. However, most signatures are collected from individual, actively involved women. Within a few days, the Stern-manifesto becomes a national scandal – and it sets off a snowball effect. The self-incrimination campaign rocks the nation for weeks, even months. A network covering the entire country slowly crystallises out of hitherto isolated anti-218 women’s groups.

22 June 1971: Aktion 218

Approximately 100 women from 20 cities take part in the delegate meeting of the Aktion 218 in Frankfurt. They count 2,345 self-incriminations by women, 973 by men, and over 86,000 declarations of solidarity.

In a letter of protest to the Minister of Justice Gerhard Jahn (SPD) they declare: “Aktion 218 and its far-reaching success are proof that women no longer understand the Gebärzwang [‘enforced delivery’] imposed on them by the state as an individual problem. For the first time, we women demand not to be treated as Stimmvieh [‘election-booth fodder’], but instead to express ourselves as active, political citizens.”

19 July 1971: Declaration of Solidarity

30 delegates from Aktion 218 present the Ministry of Justice with the 86,000 declarations of solidarity.

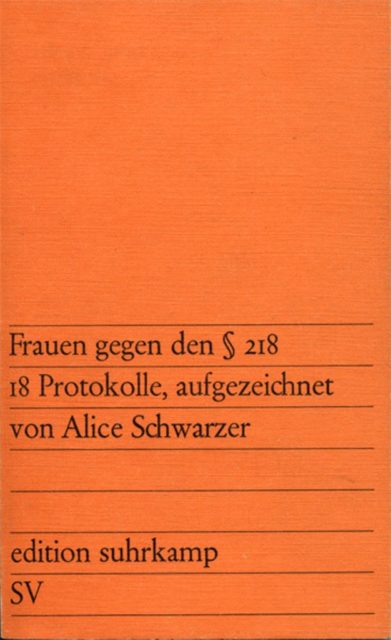

September 1971: Book Frauen gegen den §218 published

Alice Schwarzer publishes her book Frauen gegen den §218 with Suhrkamp-Verlag. It contains reports of conversations with 18 women who had abortions, an essay by Schwarzer about the history of §218 and the campaign, and a collaborative text by the Munich-based Sozialistische Arbeitsgruppe zur Befreiung der Frau – Aktion 218. The authors feared that the “CDU and SPD would perhaps join hands, this time over the ‚Indikationslösung‘, and what’s more, against the explicit demands of women in the SPD and FDP and all the women in the Aktion §218”.

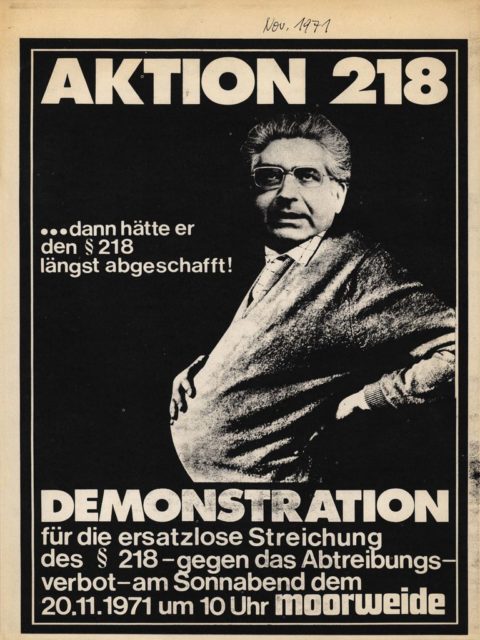

2 September 1971: Demonstrations against Reform of §218

The Minister of Justice Jahn announces a reform of §218. However, he rejects the ‚Fristenlösung‘ and instead favours the so-called ‚Indikationslösung‘: abortion should only be possible if “medico-socially”, “ethically”, or “eugenically” indicated, i.e. if the mother’s life is at risk, after rape, or in cases of foetal disability.

The SPD is split over the abortion question; in particular, the majority of social democratic women are in favour of the ‚Fristenlösung‘. The FDP is the only party to consistently demand the ‚Fristenlösung‘. – Across a number of German cities thousands of women – and like-minded men – demonstrate against Jahn’s proposition and for the elimination, without replacement, of §218. Their slogan: “Von Frauen, die er quält, wird Jahn nicht mehr gewählt!”, or “Jahn won’t be re-elected by the women he torments!”

21 February 1972: Catholic Church Puts Pressure on Politicians

With the parliamentary elections on December 3 in mind, the Catholic Church puts increasing pressure on politicians. The Cologne-based Cardinal Höffner declares: “Representatives not prepared to ensure the inviolability of human life, and also that of the unborn child, are unelectable for devout Christians.” The cabinet approves the ‚Indikationslösung‘ for the FRG.

9 March 1972: Termination of Pregnancy

East German Parliament passes the Gesetz über die Unterbrechung der Schwangerschaft. Women are allowed to terminate pregnancy without legal repercussions during the first three months after conception. The timing of the passage of the bill on the ‚Fristenlösung‘ cannot have been accidental: the leaders of the GDR want to prevent the West German women’s movement from spilling over into East Germany. In the preamble to the law, they declare: “The equality of women in education and career, marriage, and family demands that women are able to themselves decide about the progression of pregnancy.”1

11 June 1972: First German Women’s Tribunal Against §218

One year after the Stern-campaign, women in Cologne organise the ‚first German women’s tribunal against §218‘. Around 1,200 activists accuse a phalanx of politicians, church representatives, doctors, lawyers etc. with denying them their right to self-determination at the Gürzenich festival hall in Cologne.

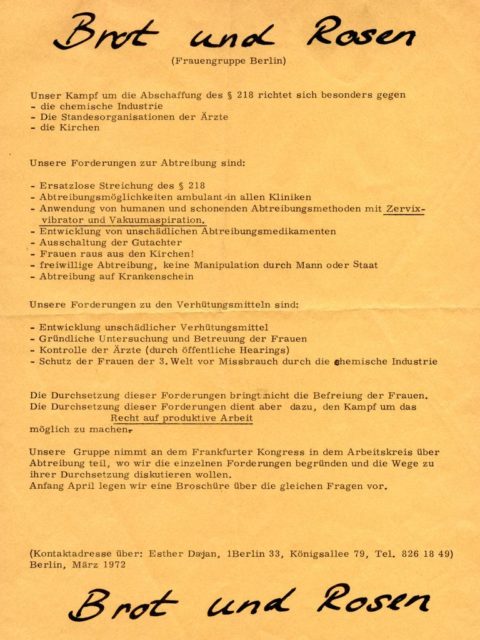

Spring 1973: Ongoing Protests

Further protests follow. Women’s groups storm the annual general meeting of the Hartmannbund and pelt the attending doctors with bags of flour and cooked noodles. In response to the Catholic Church’s restrictive abortion policy, §218-activists launch a Kirchenaustritts-Kampagne [‘a campaign of formal defection from the Catholic Church’] in March.

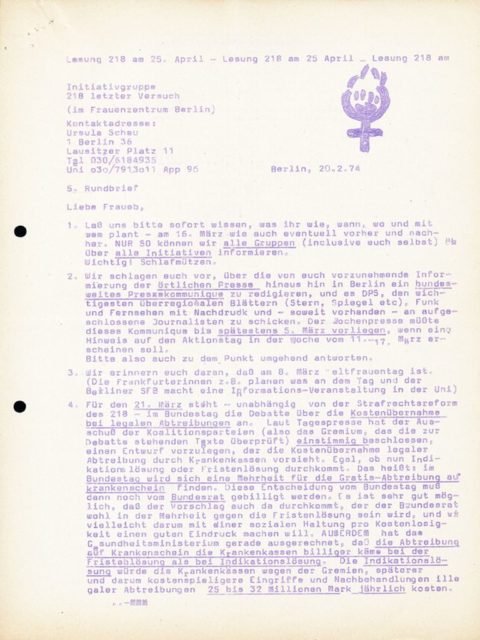

March 1974: Aktion Letzter Versuch

Because the passage of the §218 reform bill is announced for June, women’s groups from across Germany organise the Aktion letzter Versuch [‘Last Ditch Campaign’] from March 8-16. The campaign week aims to put pressure on the SPD and FDP and get them to approve the passage of the Fristenlösung. On March 11, the Spiegel prints the headline Aufstand der Schwestern [‘Sisters’ Rebellion’]. In the corresponding article, 329 doctors divulge: “We have helped women have abortions, without financial gain, and will continue to do so.”2

At the same time, the FRG experiences German television’s largest censorship scandal. Following a public announcement, on March 9 in Berlin 14 doctors perform an abortion via vacuum aspiration, a gentle method not practiced up to that point in the FRG.

The doctors assert: “Every day 2,000 to 3,000 illegal abortions are carried out in the FRG. Our campaign ought to put an end to the hypocrisy. We demand equal rights for all, the development of non-harmful methods of contraception, and child-friendly living conditions.” Alice Schwarzer, who spearheaded the campaign, films the abortion for the television programme Panorama. The episode, which was to be aired on March 11 and was approved by the director of the NDR that morning, is cancelled one hour before broadcast.

One decisive reason: the head of the German Episcopal Conference Cardinal Döpfner had brought criminal charges. In protest against the episode’s cancellation, all Panorama authors withdraw their contributions. Peter Merseburger, the managing director of Panorama, televises an empty studio for 45 minutes.

The Aktion Letzter Versuch ends on March 16 with the Nationaler Protesttag [‘National Day of Protest’].

26 April 1974: No Chance for the ‚Fristenlösung’…

With votes from the SPD and the FDP, the Bundestag passes the ‚Fristenlösung‘. However, the SPD is by no means united in favour of the Fristenlösung. The Chancellor Willy Brandt had left the chamber before the vote. He later declared that he was against abortion. The reason: he was an illegitimate child and would not have been born if abortion were legal. The CDU/CSU lodge a constitutional complaint. The law does not come into force.

25 February 1975: …Still No Chance

A federal court majority declares the ‚Fristenlösung‘ to be unconstitutional. The day before the ruling approximately 12,000 women had demonstrated for the liberalisation of the abortion law.

Two of the eight judges, however, vote in favour of the ‚Fristenlösung‘ with a Minderheitsvotum [‘minority opinion’]: Wiltraut Rupp von Brünneck, the only woman, and her colleague Helmut Simon.

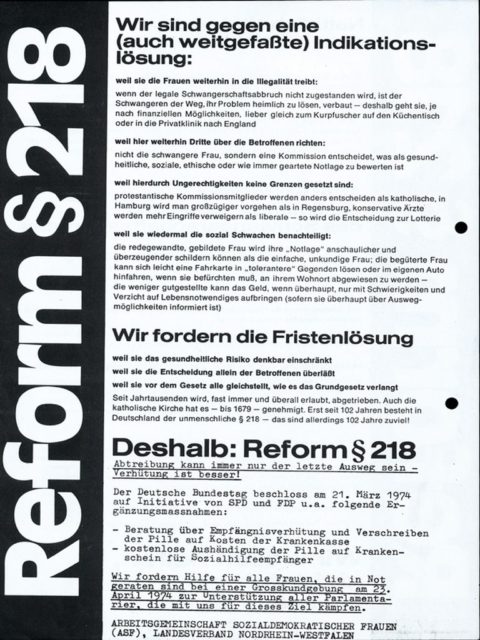

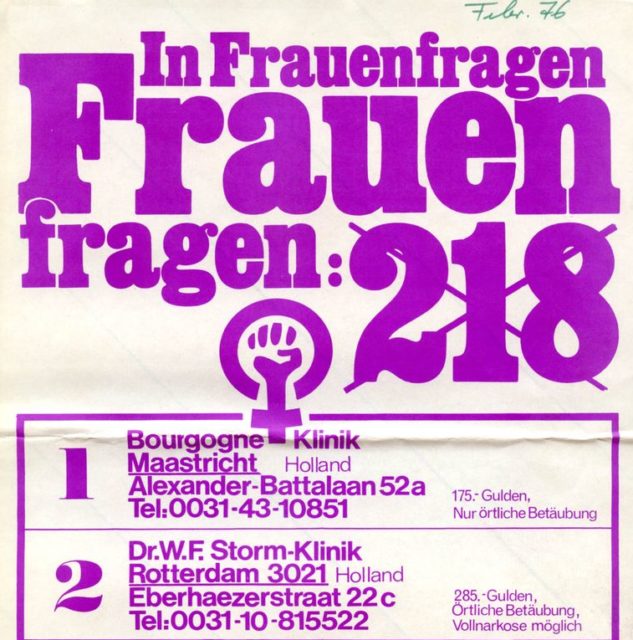

13 February 1976: ‚Indikationslösung‘

With votes from the SPD and the FDP, parliament passes the ‚Indikationslösung‘. An abortion is henceforth only exempt from prosecution if a “medical”, “criminological”, “embryopathic”, or “social” indication exists. The latter presents a loophole for women with sympathetic doctors. Termination is similarly permitted if the pregnant woman “finds herself in situation so desperate that continuing the pregnancy cannot be demanded of her”. The SPD approves this wording of the law and subsequently makes the ‚Indikationslösung‘ their cause. The result: paternalism instead of rights for women.

The women who had spent years fighting for abortion rights are furious. Women’s initiatives and centres organise further protests over the next months, e.g. demonstratively provocative bus trips to Holland, where abortion is legal. The struggle for the repeal of §218 is from now on no longer the focus of the women’s movement, but it remains – also due to its symbolic value – one of the movement’s key issues.

9-11 November 1978: Abbortion is Still Problematic

At the women’s health centre in Frankfurt around 100 participants from 30 women’s centres share their experiences of the §218 reform. In CDU-led federal states and Bavaria, the law – which only permits abortion if medically/socially, criminologically or embryopathically indicated – receives an especially narrow reading: doctors refuse to issue indications, and hospital beds are not made available for abortions. As before, tens of thousands of German women are forced to travel to Holland for a termination.

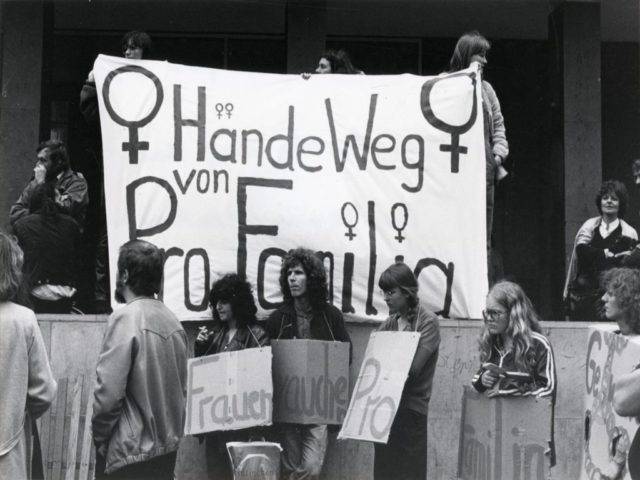

February 1979: First Pro Familia Centre

In Bremen, Pro Familia opens a family planning centre at which abortions are also performed. It is the first of its kind in Germany. Women’s groups demand “a treatment centre like the Pro Familia in Bremen in every city!”3 Further Pro Familia centres open, e.g. in Hamburg and Kiel.

September 1979: „Lebensschützer“

The liberalisation of abortion law brings the so-called ‚Lebensschützer‘ [‘pro-lifers’] onto the scene. They carry out arson attacks on several Pro Familia centres. The Catholic Church also agitates unabated against the §218 Indikationslösung. With reference to the Second Vatican Council, the Cologne Cardinal Joseph Höffner declares abortion to be a “despicable crime”.4

The German Episcopal Conference publishes the declaration Dem Leben dienen and distributes 2.5 million copies in churches. Women’s groups organise demonstrations against the Church’s attempt to overturn the legal status quo: “The nation’s moralists are sawing away at indication – women, defend yourselves!”5

1-5 September 1982: ‚Choose Life‘-Campaign

On the German Katholikentag in Düsseldorf the German Episcopal Conference and the Zentralkomitee der deutschen Katholiken launch a multi-year campaign, Wähle das Leben [‘Choose Life’]. Aim: the renewed narrowing of §218. Women’s initiatives protest against this move with various campaigns.

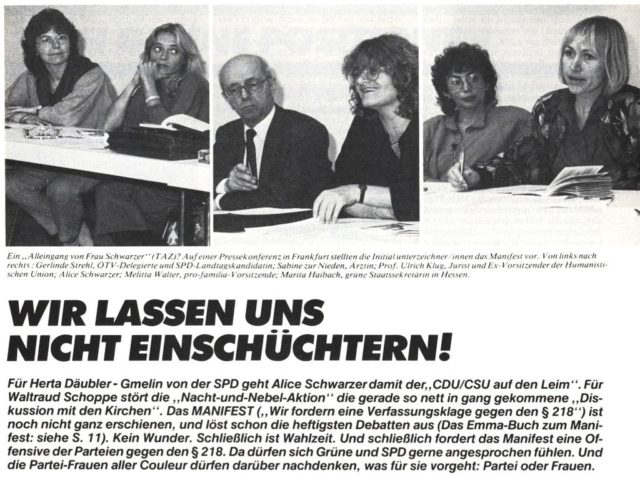

July 1986: EMMA-Manifesto

The debate receives new momentum when the magazine EMMA publishes a manifesto in which the authors call on the SPD, the FDP, and the Green Party to lodge a constitutional complaint against §218 in order to push through the ‚Fristenlösung‘. “We call on these three parties to finally put a stop to the ‘murderess’-slogans and to tackle the disgraceful paternalism and humiliation of women.” 5

The three parties do nothing. At the same time, the CDU/CSU announce they want a renewed tightening of §218. The counselling requirement is to be expanded: only counselling centres that advise women “in favour of unborn life” are to receive state recognition, and doctors are to attend courses about “protecting life”. Abortion is only to be covered by health insurance if the doctor reports the termination to the Federal Office of Statistics.

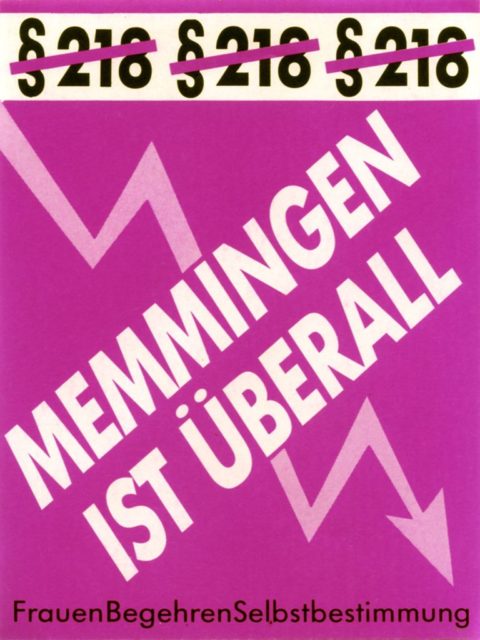

September 1988: Memmingen-Trial

In the Bavarian city of Memmingen the trial of the gynaecologist Horst Theissen begins before the district court. When the established gynaecologist is anonymously reported for tax evasion, investigators seize his patient files and pass them on to the public prosecutor’s office. The prosecution starts proceedings against 279 women for illegal abortion and brings charges against 156. The majority of these cases end with an order for summary punishment, which most of the women accept in order to prevent a public trial.

The gynaecologist Theissen is also indicted. He allegedly performed abortions without the existence of a (social) indication. The judges, against whom the defence repeatedly bring motions to disqualify on grounds of prejudice, deliberately embarrass Theissen’s patients over the course of the doctor’s trial. They summon 79 women, read out their names, and interrogate them publicly about the most intimate of details.

On May 5 1989, Horst Theissen is handed down a prison sentence of two-and-a-half years and a professional ban of a further three years. After Theissen successfully appealed, the sentence is converted to one-and-a-half years in prison and no occupational ban. The Memmingen trial – characterised by the media as a “witch hunt” or a “crusade” – goes down in history as the biggest abortion trial and attempt at the intimidation of doctors and women in German legal and women’s history.

What happens next?

Conflict over the law concerning abortion counselling occupies political parties and the women’s movement for the next three years. In July 1989 the coalition declares the law to have failed because a consensus could not be reached within the CDU and FDP. With the reunification of Germany, a new dispute over §218 erupts: the law is now to apply also to the former GDR, where the ‚Fristenlösung‘ has been in force since 1972. This time only a few women’s initiatives protest. They organise demonstrations in Berlin and Bonn and demand that the ‚Fristenlösung‘ be adopted across the entire country. The women in the GDR seem at first not to recognise the danger. They consider their right to abortion to be guaranteed.

On 26 June 1992 after 16-hour marathon negotiations, the now pan-German Bundestag passes a compromise: during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy abortion is permitted, however the pregnant woman is obliged to attend counselling beforehand and to submit certification of counselling to the operating doctor. Between counselling and termination, three days must pass. The majority for this law only materialises because (in particular) female delegates from across the parties – also the CDU – vote in favour of the law. For example, in a passionate speech Rita Süssmuth (CDU) declares: “I ask myself why, in such an extreme and conflict-laden situation, the doctor and subsequently the judge, the public prosecutor are attributed more competence and responsibility than the woman who assumes responsibility for the child not only now, but for a whole lifetime. Let’s finally stop treating women as if they are indecisive, irresponsible!”6

Following a lawsuit brought by the Bavarian government, in May 1993 the Federal Court declares the law to be unconstitutional and urges the legislator to make revisions. Parliament narrows §218: an abortion is under the aforementioned conditions “illegal but exempt from punishment”. Mandatory counselling must be documented in writing. This version of §218 is in force in Germany today. As a result, Germany has one of the most restrictive abortion policies in Europe. Pressure is still exerted by church-affiliated political circles and so-called “pro-lifers” to re-tighten the law. Christian fundamentalists, often supported by evangelical organisations from the USA, regularly organise Märsche für das Leben [‘Marches for Life’] or hassle women in front of clinics that perform abortions.

Currently, all parties seem to have come to terms with the status quo. Due to the liberal interpretation of the law, nowadays women of reproductive age suffer minimal distress. However, there are numerous indications – nationally as well as internationally – that certain anti-abortion movements are attempting to narrow the law. In Germany this inclination is marked, for example, by restrictive debates about the morning-after pill or late abortion.

References

1 Preamble to the law regarding the interruption of pregnancy, passed by the East German Parliament on March 9 1972, retrieved from: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gesetz_%C3%BCber_die_Unterbrechung_der_Schwangerschaft

2 See Spiegel Nr. 11, 11.03.1974, „Abtreibung: Aufstand der Schwestern“; retrieved from: http://www.frauenmediaturm.de/fileadmin/Images/Chronik/74/74_S3a_Abtreib_gr.jpg

3 See Pressedokumentation PD-SE.11.21, Chronologie der Auseinandersetzung um den Paragraph 218, Berichtszeitraum 01.1979-07.1979, 4. März, Pamphlet (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.11.21).

4 See Pressedokumentation PD-SE.11.21, Chronologie der Auseinandersetzung um den Paragraph 218, Berichtszeitraum 08.1979-12.1979, Frankfurter Rundschau, 11.9.1979 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.11.21).

5 ibid., Pamphlet September 1979, Aufruf zur Demo am 22.9.79 in Essen (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.11.21).

6 Renate Faerber-Husemann: „Konflikte und Errungenschaften – 20 Jahre nach Änderung des Abtreibungsrechts“, Deutschlandfunk, 24.6.2012

Date of the last linkcheck : 05.09.2018

Selective Bibliography

Documents online

Recommendations

Paragraph 218 : Dokumentation eines 100jährigen Elends (1971). - Jochimsen, Luc [Hrsg.]. Hamburg : Konkret-Literatur-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.11.051)

Schwarzer, Alice (1971): Frauen gegen den §218 : 18 Protokolle, aufgezeichnet von Alice Schwarzer. - Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.11.158)

Wir klagen an: Tribunal gegen § 218 ; Dokumentation. - Retzlaff, K. ; Degener, L. ; Hebisch, Sylvia ; Beckmann, S. ; Wellstein, U. ; Hilzinger, S. [ed.]. Hamburg: Buntbuch-Verlag, 1981. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.11.019)

Die neuen Moralisten : §218 - vom leichtfertigen Umgang mit einem Jahrhundertthema (1984). - Paczensky, Susanne von [ed.] ; Sadrozinksi, Renate [ed.]. Reinbek : Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.11.037)

Elke Kügler (1989): Memmingen: Abtreibung vor Gericht. Pro Familia, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Familienplanung, Sexualpädagogik und Sexualberatung [ed.]. - Komitee für Grundrechte und Demokratie [ed.]. Braunschweig: Holtzmeyer Verlag. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.11.019)

FMT Press Documentation

Press Documentation on The Fight against Abortion Law : Against § 218: PDF-Download

The FMT has a unique press documentation for §218, which includes 48 chronologically sorted folders. The folders contain sources of the New Women's Movement in the form of public letters, minutes, pamphlets and press articles from the feminist press, press articles from the general press, historical journal articles and abstracts from compilations, bills, parliamentary debates, speeches and inquiries as well as the judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court of 25.02.1975.

Selected FMT-Sources (lists)

FMT literature selection Abortion: Against §218: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Law, Ruling and 'Male Justice'

Law, Ruling and 'Male Justice'

As the women’s movement got under way, law was almost exclusively administered by men. Feminists analyse that there is a “male justice” › mehr

Women's Health and Patriarchal Medicine

Women's Health and Patriarchal Medicine

Self-determination and knowledge of one’s own body – women’s health initiatives were directed against a patronizing and patriarchal medicine that made the male body the point of reference while the female body was both medicalised and pathologised. › mehr

Feminist Debates on Sexuality and Love

Feminist Debates on Sexuality and Love

It was the women’s movement that questioned the function of power in sexuality and unmasked the fact that love disguises power structures. › mehr