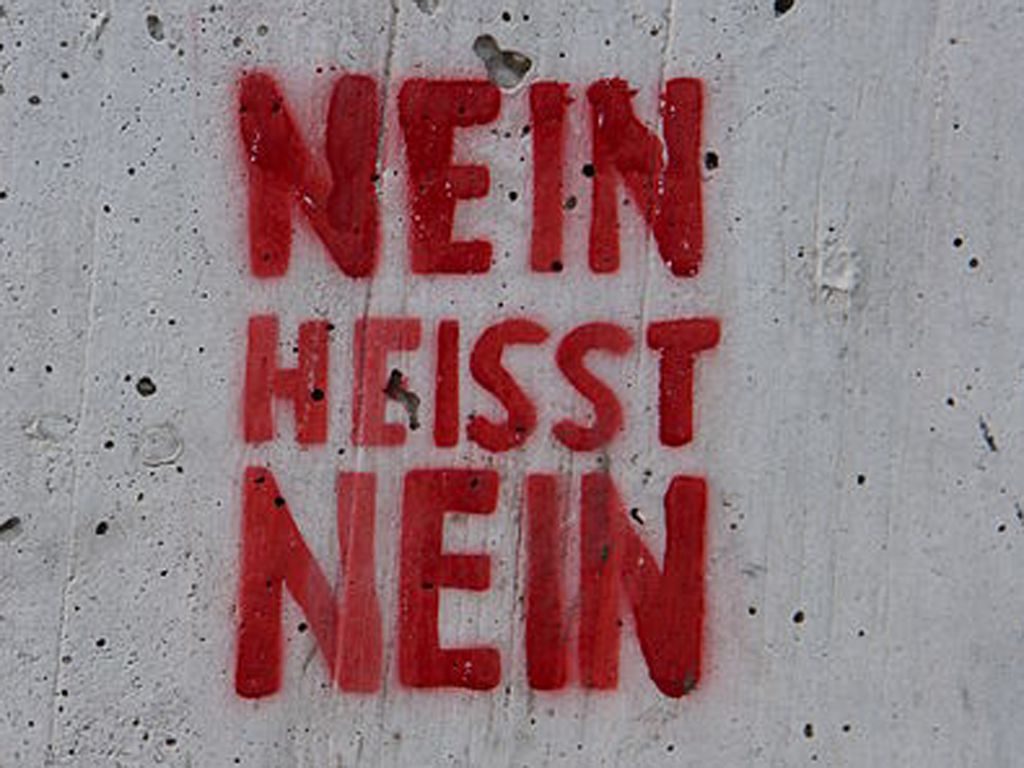

Beginning in the mid-1970s, the women’s movement brought the epidemic of sexual violence taking place behind closed doors as well as in the open to the public’s attention. Feminists concluded that rape is not the act of an abnormal ‘Triebtäter’ [‘sex offender’], but rather a transgression used in patriarchal society to systematically break and oppress women – in everyday life as well as during war. The women’s movement organised demonstrations, established hotlines for rape victims, and railed against the fact that victims were given the blame for this crime (e.g., “why was she wearing such a short skirt?”). They called for a reform of the Vergewaltigungsparagraphen §177 [‘rape paragraph’] that often led to rapists’ acquittal. They also called for marital rape to be made a criminal offence. Both demands have now been implemented: marital rape became punishable by law in 1997. However, it took until 2016 for rape to be defined in §177 as a sexual act “against a person’s will”. No finally means No.

24 November 1973: Reform of the Sex Crime Legislation

The social-liberal coalition reforms sex crime legislation. In this Vierter Großer Strafrechtsreform, ‚simple pornography‚ is exempt from punishment and the prosecution of procuring complicated by its vague definition.1 However, in a climate characterised by the struggle against §218 and for women’s right to control over their bodies, the legislature adopts a new concept of sexual offences: they are no longer considered “crimes or offences against morality”, but rather “crimes against sexual self-determination”. Thus, the focus is no longer on the woman’s morality or ‘honour’ as the object of legal protection, but on the woman’s right to full control of her body.

September 1974: 1st Women’s Group

The first women’s group Frauen gegen Gewalt gegen Frauen2 is established at the women’s centre in Berlin. The activists publish texts on the subject, observe rape trials, and plan a counselling centre for rape victims based on American rape crisis centres.

Spring 1975: Against Our Will by Susan Brownmiller

Susan Brownmiller’s Buch Against Our Will3 (German: Gegen unseren Willen, 1978) is published in the USA. In this book, Brownmiller dispels the common myth that rapes are individual acts by criminal or ‘disfunctional’ men.

![Brownmiller, Susan (1975): Against our will. - New York, NY : Fawcett Columbine (FMT-Signatur SE.03.164.[03]) Brownmiller, Susan (1975): Against our will. - New York, NY : Fawcett Columbine (FMT-shelfmark SE.03.164.[03])](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Brownmiller_Against_Our_Will.jpg)

27 February 1976: Public Attention Increases

Die Zeit reports on marital rape and violence under the headline Die Frau als Opfer der Männer. The newspaper refers to Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will. The matter of sexual violence against women, increasingly being brought to public attention by the women’s movement, is so well received that it is picked up more and more by the media.5

![Internationales Frauentribunal Brüssel 4.-8. März 1976. Frauengruppen <Bremen> [Hrsg.] - Bremen : Selbstverlag (FMT-Signatur: SE.01.038) Internationales Frauentribunal Brüssel 4.-8. März 1976. Frauengruppen [Hrsg.] - Bremen : Selbstverlag (FMT-shelfmark: SE.01.038)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Plakat_Internationales_Frauentribunal_Bruessel-546x640.jpg)

4-8 March 1976: International Tribunal – Violence against Women

1,500 participants from 33 countries, including Germany, come together in Brussels for the Internationales Tribunal Gewalt gegen Frauen.6 The women’s ‘indictments’ cover all areas of society: from marital violence and discriminatory laws to pornography. Simone de Beauvoir writes in her greeting: “I consider this meeting to be a great historical event.”7

14 April 1976: Stern Result about Rape within Marriage

The Stern publishes the results of a survey it commissioned. Title: Mein Mann hat mich vergewaltigt. Result: “In every one in five marriages, the woman is forced into having sex.” This ratio corresponds to approximately 2.5 million women in the FRG. Every one in five women is also of the opinion that a wife must be “sexually available for her husband whenever he feels like it.”8 In fact, the Federal Court of Justice had ruled in 1966 that a wife may not “endure ‘sexual congress’ with indifference”, even if she herself is unwilling.9

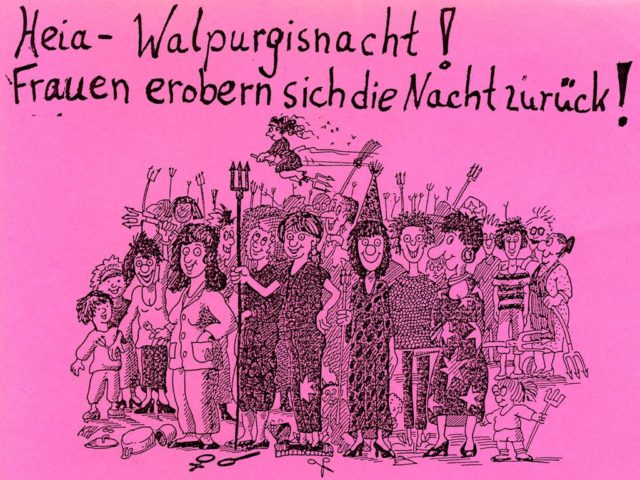

30 April 1977: “We’re Reconquering the Night!”

Women organise the first Frauen-Nacht-Demo against sexual violence in Berlin. Reason: 26-year-old Susanne Schmidtke had been raped and so savagely beaten in Charlottenburg that she died of her injuries three weeks later. The campaign pamphlet states: “35,000 women are raped every year in the FRG and West-Berlin. That means: 51% of the population have curfews in the evening, namely all women, from little girls to old-age pensioners. […] Women, let’s stop taking this as a matter of course! Let’s scream back, let’s hit back, let’s defend ourselves together!”10

Over the following years, women organise similar night marches across many cities. Motto: “Wir erobern uns die Nacht zurück!”, “we’re reconquering the night!” Most marches take place on the night of 30 April to 1 May, i.e. on so-called Walpurgisnacht.11

August 1977: § 177 – How the Legal System Deals with Women who Report Being Raped

In her article Die Rechtsprechung zur Vergewaltigung – Über die weit gezogenen Grenzen der erlaubten Gewalt gegen Frauen12 for the journal Kritische Justiz, the lawyer Alisa Shapira analyses how the legal system deals with women who report being raped. She ascertains: “In 1975, sexual assaults constituted only 3% of all offences recorded by the police. Only a very small proportion of these cases are heard in court, and about one third of the defendants are acquitted.” After analysing various trials and supreme court judgements, Schapira comes to the conclusion: “The legal system’s use of generic myths about femininity to judge rape has the consequence that violence between the genders continues to enjoy considerable room to manoeuvre within the legal framework. On one hand, violence is only in extreme cases a criminal act in the sense of §177 StGB; on the other, an assumption about female masochism means that women are held to be not credible in court. Inquisitorial questioning of women about their ‘past’ is the result […].” The lawyer calls for a “de-ideologisation of case law”.

According to Schapira, the legislature still stands in the “tradition that sees rape as a transgression against male ownership of woman.”13 Schapira’s article is read widely.

October 1977: Against Our Will – German Translation

In three separate installments, EMMA releases an advance publication of the German translation of Susan Brownmiller’s Against Our Will.

28-30 April 1978: National Tribunal – Violence against Women

At the initiative of the Kölner Frauenzentrum, delegates from women’s centres organise a Nationales Tribunal Gewalt gegen Frauen. The ‘catalogue of violence’ that the initiators put together stretches from ‘fashion and beauty terror’ and ‘male-orientated language development’ to ‘marital violence’.14

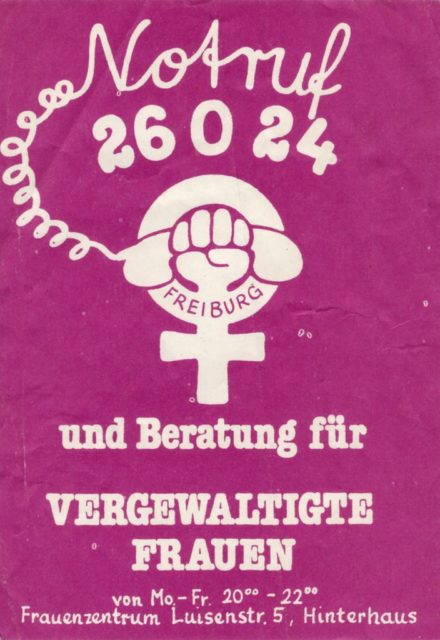

End of 1970s: 1st Women’s Emergency Hotlines

Women establish the first women’s emergency hotlines in order to help victims of rape and other forms of (sexual) violence.15 Over the following years, approximately 120 emergency hotlines will be created.

24 February 1980: Call for Punishment of Husbands

In 1983, the lawyer Dierk Helmken calls for the punishment of husbands who force their wives to sleep with them in his book Vergewaltigung in der Ehe – Plädoyer für einen strafrechtlichen Schutz der Ehefrau16 In an interview with the Heidelberger Rundschau (HR), Helmken states: “Currently the legislature virtually forces women to fight back, so as later to be able to prove ‘I didn’t let it happen to me willingly’. This has the consequence that they run the risk of provoking their husbands to an even worse assault that could result in serious injury or even death […]. One only dares venture onto the territory of marital rape if the organs of law enforcement have as much freedom as possible to deal with the specifics of each individual case.”17

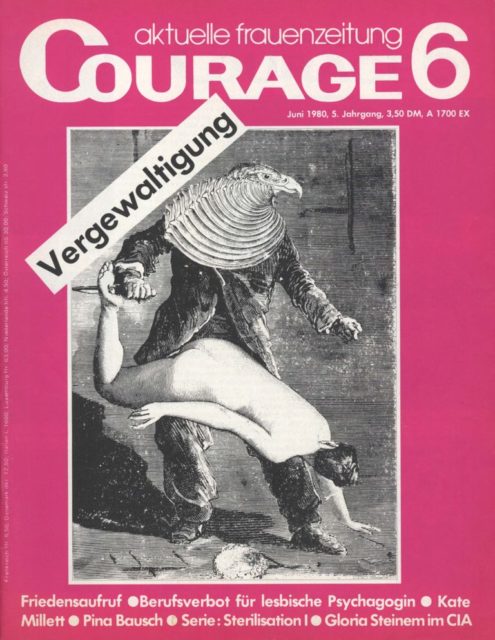

June 1980: § 177 (Rape) & § 178 (Sexual Assault)

In a special issue of Courage on the subject of rape, the lawyer Ingrid Lohstöter calls for consistent rape reporting, despite criticism of the current interpretation of §177 StGB: “Case law will only change if more and more rape cases are tried, the number of unreported rapes is reduced, the procescution and the courts are called to account, and our arguments and self-image as women are represented, also to the Männerjustiz.”18 A call by the Berliner Notruf und Beratung für vergewaltigte Frauen and other women’s groups to tighten §177 (rape) and §178 (sexual assault) of German criminal code is published in the same volume: “When women say no, they also mean no!”19

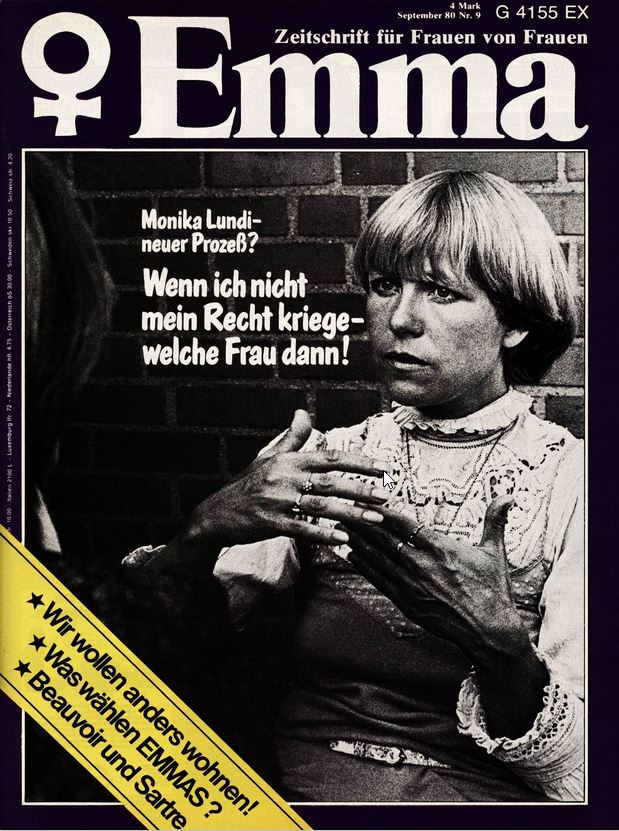

28 July 1980: The Case “Monika Lundi”

The verdict is pronounced in the trial against the actor Burkhard Driest, whose colleague Monika Lundi had reported him for rape.20 Driest is fined 500 dollars by the Santa Monica Court, California for assault; the rape allegation is dropped.

Lundi had attended an acting seminar in Santa Monica with several colleagues and had accompanied Driest and Jürgen Prochnow to their accommodation after having had dinner together. In an interview with EMMA Lundi describes how, after she had fallen asleep on the sofa, Driest dragged her onto the carpet by her hair, hit her repeatedly, and finally raped her. The hospital that treated Lundi’s injuries informed the police, who arrest Driest. The court case becomes a show trial against the alleged victim Lundi, who is made to appear – as per usual for rape trials – not credible by the defence. EMMA conducts an Interview with Monika Lundi and headlines the case. Lundi: “They hounded me like an animal.”

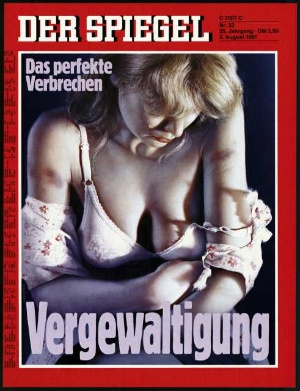

3 August 1981: Rape – The Perfect Crime

The Spiegel headlines the story Vergewaltigung – das perfekte Verbrechen and states that a “militant mood […] has also gripped women in the Federal Reupblic of Germany”.21 Examples: “Following the successful defence of a client charged with rape, the Berlin-based lawyer Niklas Becker was visited by 50 women. The women draped lingerie around his law firm, sprayed perfume, and hung a sign around the lawyer’s neck that read ‘Zuhälteranwalt’, ‘pimp lawyer’.

At the magistrates’ court in Berlin, a feminist group turned a rape trial into a happening by means of a large purple cardboard penis. In Hamburg women with posters were asked to cheer the victim in a sexual assault trial: ‘Show up in great numbers and lend her your support.’”22 The Spiegel notes: “Due to the unparalleled number of unreported rapes, at most 1% of all rapists can expect to be reported and convicted of their crime. Hans Joachim Schneider, head of the institute for criminology at the University of Münster, says that “those who choose their victim and the scene of the crime well can practically eliminate the risk of punishment.”23 (35 years later, in 2016, EMMA writes: “Only every one in 100 rapists are convicted in Germany.”24)

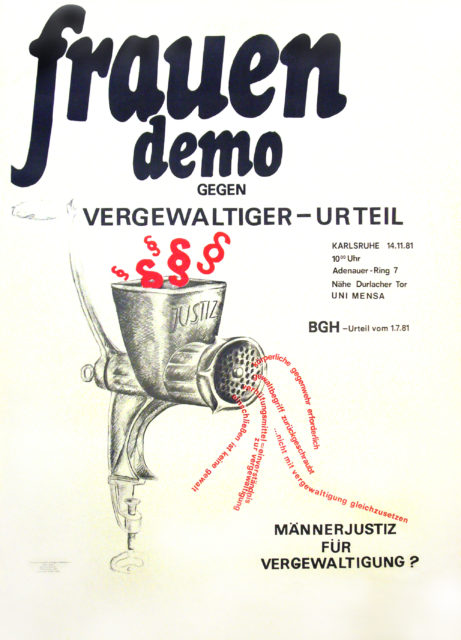

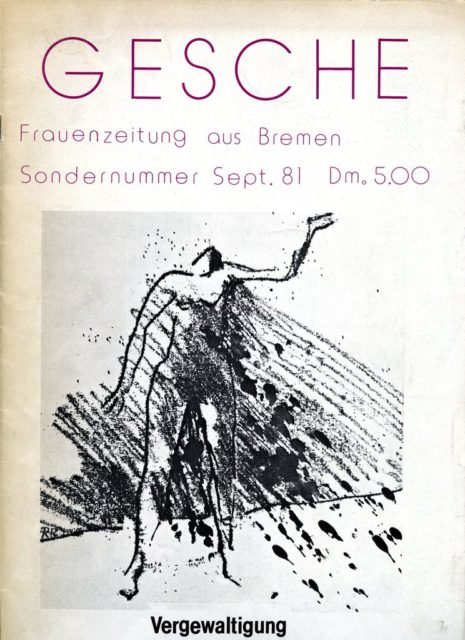

September 1981: The Issues with Law and Policy

The opinion piece Wir nehmen die Kriegserklärung an! by Alice Schwarzer is published in EMMA. The reason for the text is a verdict handed down by the Federal Court of Justice on 1 July 1981. The Federal Court of Justice had quashed the verdict against a 39-year-old master painter and decorator, who had previously been sentenced to six years in prison by the district court in Wuppertal for the multiple rape of his female apprentice. The perpetrator had time and time again driven the young woman into the woods in his delivery van, locked the vehicle, and raped the woman. The judges in Karlsruhe don’t doubt that sexual intercourse had taken place without the consent of the apprentice. However, neither “the mere driving of the woman to a remote place where she could not expect to receive help”, nor “the locking-in or similar restrictions to the woman’s freedom of movement with the intention to engage in sexual intercourse with her” can be considered use of force according to §177.

Schwarzer writes: “Now of all times, when women finally dare to talk about their humiliation and fear; (…) now of all times, when women are analysing the subtile interconnection of intimidation, shame, and fear – now of all times, a federal court answers on exactly this level! And that’s exactly what the federal court wants. That’s why this verdict is a direct answer to the work of the women’s movement! That’s why it’s a hugely political judgement!”

The Bremen women’s newspaper Gesche publishes the special issue Vergewaltigung, put together by the women from the Bremer Notrufs für vergewaltigte Frauen e.V.. They complain that rapes within the “so-called left-wing or alternative scene” are not being reported and that the rapist is “sometimes pitied […] because only his social situation allegedly has made him become a rapist (and no one mentions the woman)”. According to Gesche, violence against women is not an issue discussed in the left-wing scene. The conclusion of one author: “I would rather not have seen this ideological break because it affects my identity; it has me asking if I want to attend another demonstration if (for example) the freak next to me defends me against the cops, but two hours later would like to ‘smash my face in’ because I’m a ‘Scheiß-Emanze’, a ‘bloody woman’s libber’.”25

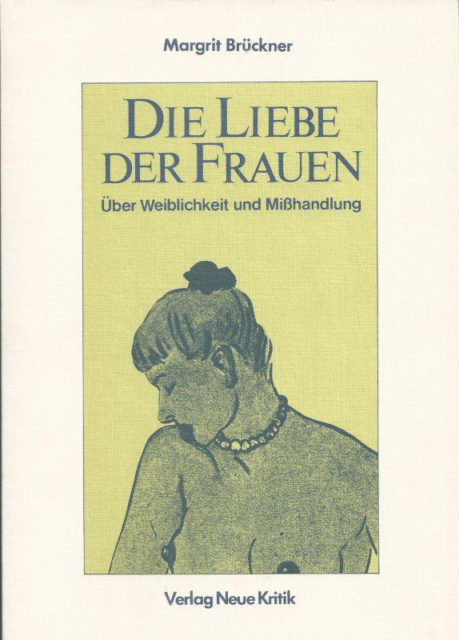

1983: Between Love and Hate in Violent Relationships

The sociologist Margit Brückner’s dissertation is published with Neue Kritik as Die Liebe der Frauen: über Weiblichkeit und Mißhandlung.26 Based on her experience of battered women in women’s refuges, Brückner examines the relationship between love and hate in violent relationships: “Abused women often express their astonishment that they have let themselves become so deeply dependent on a violent man, that they have put up with the situation for so long. […] One explanation for sinking into dull dependency might be the fear of becoming as powerfully overwhelmed by pent-up hatred as they once were by romantic fantasies. Because to carry on passively means protection from the full force of outbursts of hatred.”27

July 1983: Marital Rape in Criminal Law

The first political initiative to include marital rape in criminal law is launched by the Hamburg Senator of Justice Eva Leithäuser (SPD), who wants to introduce the bill to the Federal Council. With votes from the CDU/CSU and the FDP, the motion from Hamburg is rejected by the Federal Council.28

In the same month, the SPD introduces a bill in parliament which seeks the punishment of husbands who rape. The Green Party also presents a bill which aims to have the word ‘außerehelich’, ‘extramarital’ removed from §177 (rape), §178 (sexual assault) und §179 (sexual assault of vulnerable persons).29

1. December 1983: Feminist Theory – Rape as Power over and Contempt for Women

The Bundestag debates the applications by the Greens and the SPD.30 Representatives from the CDU/CSU and the FDP do not deny that sexual self-determination can be upheld within marriage; however, the debate proceeds in such a way that the lawyer Dierk Helmken declares that he has the suspicion that the reform’s opponents are ultimately concerned with defending patriarchal privileges.31 The Bundestag refers the bill to the committees for law, health, youth and family.

The final report of the study Vergewaltigung als soziales Problem – Notruf und Beratung für vergewaltigte Frauen – financed and published by the Ministry for Youth, Family, and Health – is released. Ulrike Teubner, Ingrid Becker, and Rosemarie Steinhage from the Notruf- und Beratungsgruppe based in the women’s centre in Mainz had researched the causes and the consequences of sexual violence for over two and a half years. They follow the core feminist theory that rape is “in the majority of cases not an expression of sexual needs or wishes, but rather an expression of power over and the contempt for women.”32

12/13 January 1984: Symposium – Violence against Women

The Federal Ministry of Family Affairs organises a Fachtagung Gewalt gegen Frauen in Bonn. Social workers, lawyers, doctors, police officers, journalists, women from (autonomous) women’s refuges, and representatives from the hotlines for rape victims discuss the manifestations and causes of violence against women and aid options.33

21 January 1984: Marital Rape in Foreign Countries

The Federal Ministry of Family Affairs commissions a legal report on the criminal liability of maritial rape in foreign penal codes from the Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht. The report notes that “in many countries there are ongoing efforts to strengthen the legal protection of wives”.34

Marital rape is already a criminal offence in some countries, e.g. in Sweden, France, and 19 US states.35 The opponents to a change in criminal law argue that the state must take care not to intervene in spouses’ private lives. What really takes place at home in the marital bed will never be able to be established with absolute certainty in court, and “the woman’s testimony alone cannot be sufficient evidence.”36

March 1984: Interview with the Minister of Family Affairs

In an interview with EMMA, the Federal Minister for Family Affairs Heiner Geißler (CDU) expresses sympathy for the call for a law that will make marital rape a criminal offence: such a law would make clear to men that “even within marriage, the woman is not the man’s object or property, with whom he can do as he pleases.”

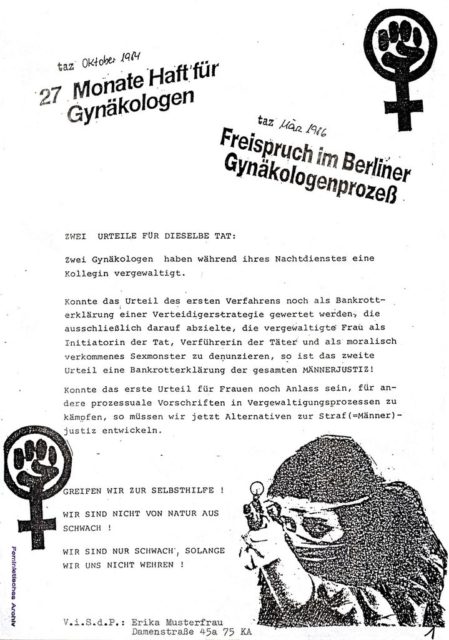

12 September 1984: The ‘Gynaecologists Process’

The verdict in the so-called Berliner Gynäkologenprozess, a trial that occupied the public for months, is announced by the district court in Berlin.37 The two doctors on trial are sentenced to two years and three months imprisonment for rape, sexual assault, and aggravated battery. The court found the prosecution to have proven that the doctors had together raped a female colleague during a night shift at Berlin’s pulmonary hospital. The trial had particularly attracted attention because both defendants (considered to be ‘progressive’) “had stopped at nothing to portray the rape victim – a female doctor – as a ‘sex-crazed monster’ and a ‘hysteric’”. This defence strategy, common at rape trials, is for the first time not only harshly criticised by feminists, but also by the media. The Süddeutsche Zeitung writes of the “defeat of rule of law if victims of a crime talk about criminal proceedings as the ‘worst experience of my life’. Something has to be done.”38

January 1985: Demands for Legal Treatment

EMMA writes: “Since the start of the women’s movement, rape – for centuries hushed-up and declared a private matter – is no longer taboo.” The feminist magazine lists the demands that feminist lawyers as well as workers at women’s emergency hotlines and counselling centres (among others) have put together with the aim that rape victims are treated appropriately by the legal system and more rape trials end in convictions. These demands include the training of police officers and the establishment of special units for prosecuting sex crimes. The victims should have the institutional right to an ancillary suit, and questions about the ‘private sex life’ of the victim should be kept to a minimum. Marital rape should be a criminal offence; anal and oral penetration should be considered rape and given the same criminal status as vaginal rape.

15 May 1997: Law Reform – Rape within Marriage

Only now does the Bundestag reach a decision about the criminal liability of rape within marriage. The word ‘außerehelich’, ‘extramarital’ is removed from the new version of the law. The landmark legal reform – for which the women’s movement and committed female politicians have fought for a quarter of a century – was only possible because female politicians from across the parties voted in favour of the revisions and put pressure on their male colleagues. Thus, they also managed to implement the redaction of the so-called ‘Widerspruchsklausel’ from the original bill: the CDU/FDP coalition had originally envisaged that wives who reported their husbands for rape could withdraw their complaint. This would have exposed wives to substantial pressure from their husbands. In order to prevent this passage from entering law, the women’s coalition led by Ulla Schmidt (SPD) presented a collective application without this ‘Widerspruchsklausel’ (EMMA reported). It was passed with the votes of almost all CDU/CSU women and some CDU/CSU men, part of the FDP, and all votes from the SPD, the Greens, and PDS. 138 MEPs – including Horst Seehofer (CSU), Norbert Blüm (CDU), and Burkhart Hirsch (FDP) – voted against the redaction of the clause.

The reform includes a redefinition of the term ‘rape’. From now on all forms of penetration – including anal and oral – are considered rape. Thus, two key demands of the women’s movement with respect to sex crime legislation are fulfilled.

1999: Federal Network Office for Women’s Emergency

The approximately 120 women’s emergency hotlines establish a Bundesvernetzungsstelle der Frauennotrufe under the direction of the women’s emergency call centre in Kiel. The start-up funding is provided by the Ministry for Women’s Affairs.

What Happens Next?

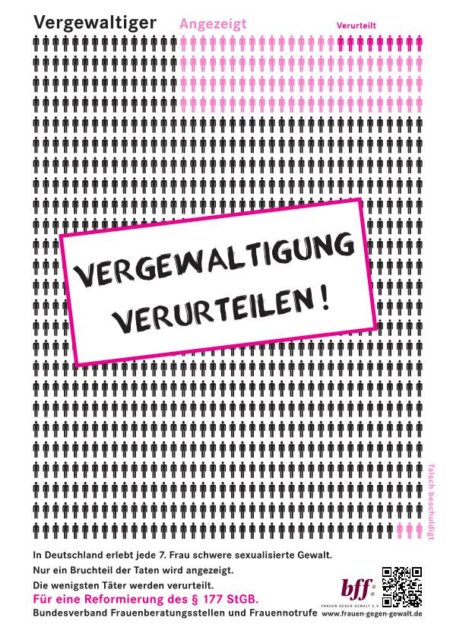

The network Bundesverband autonomer Frauennotrufe (BaF). is created in 2002. In November 2004, the BaF joins forces with the Bundesverband der Frauenberatungsstellen to form the Bundesverband Frauenberatungsstellen und Frauennotrufe – Frauen gegen Gewalt (bff). The bff turns out to be an important lobbyist in the fight to improve rape legislation. The organisation will contribute to exposing existing loopholes in legislation by documenting around 100 rape cases. That sexual intercourse was forced is undisputed in the documented cases, but the proceedings were nevertheless stopped or the perpetrator acquitted because – according to the legal professionals – the woman had not resisted enough or fled.39

In December 2004, the Ministry for Women’s Affairs publishes the study Lebenssituation, Sicherheit und Gesundheit von Frauen in Deutschland. With 10,000 respondents, it is the largest study of unreported cases of violence against women that has ever been produced in Germany. A key result: at least every one in seven women above the age of 16 has experienced sexual violence (i.e., rape or sexual assault). However, only every one in 12 reported the crime. This figure does not include child abuse.

In 2006, the Federal Court of Justice again confirms the definition of violence that it had applied in the conviction of a rapist in 1981. The Court of Justice’s grounds for the perpetrator’s acquittal are as follows: the fact that “the defendant had torn the plaintiff’s clothing from her body and engaged in sexual intercourse against her explicit will” does not prove the “coercion by force of the victim”.40 Action groups like the bff and the Deutsche Juristinnenbund launch campaigns and legislative initiatives for a reform of sex crime legislation that takes the principle ‘No means No’ into account: in order to satisfy the charge of rape, it has to be enough that the perpetrator violates the express will of the victim, without the latter having to put up substantial resistance.

The speaker of the Bundesverband Frauenberatungsstellen und Frauennotrufe (bbf) Katja Grieger states: “We have noticed that rape victims are increasingly met with reservations.” That being so, the bff extends an invitation to the conference Streitsache Sexualdelikte – Frauen in der Gerechtigkeitslücke on 2 September 2010.41 Approximately 200 advisors, lawyers for the prosecution and judges, forensic scientists and trauma therapists debate the question “how can we close the fairness gap?” The bff’s statistics show that in Germany rape goes virtually unpunished: in 2008, 7,292 women reported a rape. Approximately three quarters of rape proceedings are discontinued by the prosecution. Only every one in seven charges results in a conviction of the accused. If we assume that only every one in 12 offences is reported, 95% of perpetrators go unpunished.42

On 6 September 2010, the trial of the weatherman Jörg Kachelmann begins at the district court in Mannheim. The trial addresses the explosive issue of sexual violence within relationships. The trial lasts eight months. In the end, the accused is acquitted on the principle ‘in dubio pro reo’. The judge elaborates: “Today’s acquittal is not based on the chamber’s belief in Mr. Kachelmann’s innocence and therefore, in turn, on a false accusation of the plaintiff.” He calls on the media: “When you talk or report about the case in future, remember that Mr. Kachelmann may not have committed the crime and was therefore wrongfully brought before the court as a criminal. However, conversely also remember that Ms. D. may have been the victim of a serious crime.”

The media assesses the verdict as proof of Kachelmann’s innocence. As a result, there are further trials and verdicts. Kachelmann sues his ex-lover for damages for the expert reports that he had commissioned. While the district court in Frankfurt rejects his claim, in September 2016 the Regional Court of Appeals declares – after a hearing that lasts only two days – that Claudia D. had “deliberately and untruthfully accused Kachelmann of rape”. However, the prosecution in Mannheim, which is now forced to investigate Claudia D. for “unlawful detention”, notes that: the “circumstantial and direct evidence to be evaluated” points “in several directions and permits different sequences of events to seem possible.”43

„Wir stellen fest, dass vergewaltigten Frauen heute wieder verstärkt mit Vorbehalten begegnet wird“, erklärt Katja Grieger, Sprecherin des Bundesverband Frauenberatungsstellen und Frauennotrufe (bff). Der bff lädt deshalb am 02. September 2010 zum Kongress Streitsache Sexualdelikte – Frauen in der Gerechtigkeitslücke.45 Rund zweihundert BeraterInnen und ProzessbegleiterInnen, StaatsanwältInnen und RichterInnen, RechtsmedizinerInnen und TraumatherapeutInnen debattieren über die Frage „Wie kann die ‚Gerechtigkeitslücke‘ geschlossen werden?“ Die Zahlen des bff belegen, dass Vergewaltigung in Deutschland ein nahezu strafloses Verbrechen ist: Im Jahr 2008 zeigten 7292 Frauen eine Vergewaltigung an. Rund drei Viertel der Vergewaltigungs-Verfahren werden von den Staatsanwaltschaften eingestellt. Nur jede siebte Anzeige endete mit einer Verurteilung des Beschuldigten. Geht man davon aus, dass nur jede zwölfte Tat angezeigt wird, gehen 95% der Täter straffrei aus.46

On 1 August 2014, the Council of Europe’s Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence comes into force. The so-called Istanbul Convention requires that non-consensual sex be punished as rape: “Consent must be given voluntarily as the result of the person’s free will assessed in the context of the surrounding circumstances”.

In September 2014, the Minister of Justice Heiko Maas (SPD) presents a comprehensive reform of sex crime legislation. It addresses a variety of areas, like child pornography and sexual harrassment on the internet. However, the minister sees “no need for action” with respect to a reform of §177.44 Women’s organisations protest – e.g., with a petition that collected 20,000 signatures. Finally, the Ministry of Justice presents a draft reform of §177. It contains some improvements, however the principle of ‘No means No’ is not implemented.45 The draft thus violates the Istanbul Convention.

31 December 2015. At Cologne Central Station a mass sexual assault of women and girls by approximately 2,000 predominantly Arab and North African men takes place on New Year’s Eve. The shock caused by this event leads to the nationwide resurgence of the debate about sexual violence against women. In this climate, the Minister of Justice Maas presents his reform bill again, which had been put on ice. On the 8-9 January and at the initiative of the head of the CDU Frauenunion Annette Widmann-Mauz, the federal board of the CDU declares in its Mainzer Erklärung: “Sex crimes are not trivial offences. (…) Therefore, we want to ensure that the legal loophole with respect to rape is closed according to Art. 36 of the Instanbul Convention. To be guilty of the offence, a clear ‘no’ must suffice.”46

![Der Schock - die Silvesternacht von Köln (2016). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Kiepenheuer & Witsch. (FMT-Signatur: SE.01.187) Der Schock - die Silvesternacht von Köln (2016). - Schwarzer, Alice [Hrsg.]. Köln : Kiepenheuer & Witsch. (FMT-shelfmark: SE.01.187)](http://frauenmediaturm.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Schwarzer_Der_Schock-1.jpg)

On 1 June 2017, the Bundestag ratifies the Istanbul Convention. In 80 articles, the Übereinkommen des Europarates zur Verhütung und Bekämpfung von Gewalt gegen Frauen und häuslicher Gewalt sets out common European standards for combatting violence against women and requires signatory states to take concrete measures to protect women from violence. Germany had already signed the convention in 2011, but was only able to ratify it six years later because §177 had, until its reform in 2016, violated the Istanbul Convention.

References

1 § 184 StGB : Verbreitung pornographischer Schriften (1973). - Retrieved from: http://lexetius.com/StGB/184,12. See also Stümper, Alfred (1974): Maßnahmen zur wirksamen Bekämpfung der Zuhälterei. - In: Kriminalistik : Zeitschrift für die gesamte kriminalistische Wissenschaft und Praxis, Nr. 3, see Pressedokumentation: Prostitution : Politik und Justiz, Kapitel 2 Urteile und Prozesse, (FMT Shelf Mark PD-SE.15.04).

2 Vorwort zu unserer Gruppe Frauen gegen Gewalt gegen Frauen (1974). – Frauenzentrum Berlin [Hrsg.]. [Pamphlet], see Pressedokumentation: Chronik der Neuen Frauenbewegung 1974, Kapitel 3.2. Dokumente Chronologie der Ereignisse - 17 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD.FE.03.01-1974).

3 Brownmiller, Susan (1975): Against our will : men, women and rape. - New York : Simon and Schuster (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.03.164.[01]).

4 See also Pressedokumentation: Chronik der Neuen Frauenbewegung 1975 (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-FE.03.01-1975).

5 See also Pressedokumentation: Vergewaltigung : Debatte über Vergewaltigung als Mittel zur Unterdrückung und Beherrschung von Frauen (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.05).

6 Internationales Frauentribunal Brüssel 4.-8. März 1976 (1976). - Brüssel : Selbstverlag (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.01.038) and Gewalt gegen Frauen in Ehe, Psychiatrie, Gynäkologie, Vergewaltigung, Beruf, Film und was Frauen dagegen tun : Beiträge zum Internationalen Tribunal über Gewalt gegen Frauen, Brüssel März 1976 (1976). - Frauenzentrum

7 Grußwort von Simone de Beauvoir zum Internationalen Frauentribunal (1976). - In: AUF : eine Frauenzeitschrift, Nr.7, p. 10 (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-A001:1976-7).

8 „Mein Mann hat mich vergewaltigt“ (1976). - In: Stern, Nr. 17, see Pressedokumentation: Vergewaltigung : Debatte über die Forderung nach Strafbarkeit von Gewalt in der Ehe II (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.09).

9 BGH: Urteil vom 2. November 1966 : AZ. IV ZR 239/65. - Retrieved from openjur.de/u/270402.html

10 Frauenzentrum Berlin (1971): Frauen, wir erobern uns die Nacht zurück! [Pamphlet] (FMT Image Archive, Image ID: FB.07.104).

11 Frauen gegen Männergewalt : Die „Hexen“ kommen wieder! ; Frauen-Nachtdemo und anschließendes Frauenfest (1978). - In: [Flugblatt Frauenzentrum Langenfelderstr., Hamburg], see Pressedokumentation: Gewalt gegen Frauen : feministische Initiativen gegen Gewalt II - Demos und Kampagnen: PD.SE.01.09, Kapitel 2. Walpurgisnacht-Demonstrationen).

12 Schapira, Alisa (1977): Die Rechtsprechung zur Vergewaltigung : über die weit gezogenen Grenzen der erlaubten Gewalt gegen Frauen. - In: Kritische Justiz, Nr. 3, p. 230 f. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.03-a). Article also available online. Retrieved from: http://www.kj.nomos.de/fileadmin/kj/doc/1977/19773Schapira_S_221.pdf [PDF Document].

13 Ibid.

14 See also Tribunal Gewalt gegen Frauen : Frauen kämpft gegen Mißhandlung in der Ehe, Abtreibungsverbot, Frauenlohngruppen und Hausarbeit, Frauenfeindlichkeit in der Werbung, Erziehung zur Duldsamkeit (1978). – o.O. : Selbstverlag (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.01.040).

15 See Pressedokumentation: Gewalt gegen Frauen : Feministische Initiativen gegen sexuelle Gewalt I - Nachttaxi und Notruf (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.01.08).

16 Helmken, Dierk (1979): Vergewaltigung in der Ehe : Plädoyer für einen strafrechtlichen Schutz der Ehefrau. Heidelberg : Kriminalistik-Verlag (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.03.014).

17 Ludwig, Mia ; Tripp, Ulla ; Helmken, Dierk (1980): Vergewaltigung in der Ehe : „Egal, ob sie will, oder nicht – jetzt ziehen wir das durch“ - Ursprünglich in: Heidelberger Rundschau, Nr. 8, 15. April 1980. Reprinted in and cited from: Die Tageszeitung, 24.04.1980, see Pressedokumentation: Vergewaltigung: Debatte über die Forderung nach Strafbarkeit von Gewalt in der Ehe II (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.09).

18 Lohstöter, Ingrid (1980): Wann eine Vergewaltigung für die deutsche Justiz eine Vergewaltigung ist. - In: Courage : Berliner Frauenzeitung, Nr.6, pp. 24 – 28 (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-Ü104:1980-6).

19 Notruf und Beratung für vergewaltigte Frauen, Berlin (1980): Wir fordern ein neues Gesetz. - In: Courage : Berliner Frauenzeitung, Nr.6, p. 29 ff. (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-Ü104:1980-6).

20 See Pressedokumentation: Vergewaltigung: exemplarische Prozesse und Urteile, Kapitel 1 Prozess Driest / Lundi (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.03).

21 Vergewaltigung: „Mord an der Seele“ (1981) - In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 32, pp. 50-62. - Retrieved from: http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-14333818.html

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Schwarzer, Alice (2016): Die desaströsen Folgen des Falles Kachelmann. - In: EMMA, Nr. 6, p. 17 (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-Ü107:2016-6).

25 Ibid., p. 32.

26 Brückner, Margrit (1983): Die Liebe der Frauen : Über Weiblichkeit und Mißhandlung. - Frankfurt am Main : Verlag Neue Kritik (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.01.006).

27 Ibid., p. 112.

28 Gerste, Margit (1986): Augen zu und durch : Das Gesetz kennt keine Vergewaltigung in der Ehe. - In: Die Zeit, 04.07.1986. - Retrieved from: www.zeit.de/1986/28/augen-zu-und-durch

29 Ibid.

30 Deutscher Bundestag (1983): Plenarprotokoll 10/40, 40. Sitzung, Bonn, 01.12.1983, See Pressedokumentation: Vergewaltigung : Debatte über die Forderung nach Strafbarkeit von Gewalt in der Ehe I (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.08).

31 Helmken, Dierk (1985): Zur Strafbarkeit der Ehegattennotzucht : ein Beitrag zur Reform des Sexualstrafrechts. - In: Zeitschrift für Rechtspolitik (ZRP), Nr. 7, pp. 171-174 (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.03-a). Literally: “There is a suspicion that many who use this argument have simply adopted a rational fallback position after the last legal bastions in the fight between patriarchy and equal rights could not be constitutionally defended” (p. 172).

32 Ibid., p. 29.

33 Dokumentation der Fachtagung "Gewalt gegen Frauen" des Bundesministers für Jugend, Familie und Gesundheit vom 12. und 13. Januar 1984 in Bonn (1984). - Bundesministerium für Jugend, Familie und Gesundheit / Arbeitsstab Frauenpolitik [Hrsg.]. Bonn : Selbstverlag (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.01.001).

34 Meyer, Jürgen (1984): Gutachten über die Strafbarkeit der Vergewaltigung in der Ehe nach ausländischen Strafgesetzen. Max-Planck-Institut für ausländisches und internationales Strafrecht, p. 10 f., see Pressedokumentation: Vergewaltigung : Debatte über die Forderung nach Strafbarkeit von Gewalt in der Ehe I (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.08). See also: Schalkhäuser, Vera (1985): Rechtsgutachten über die Strafbarkeit von Vergewaltigung in der Ehe in ausländischen Strafgesetzen (Zusammenfassung und Anmerkung). - In: Streit : Feministische Rechtszeitschrift, Nr. 3 (FMT Shelf Mark: Z-F011).

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 See Pressedokumentation: Vergewaltigung: exemplarische Prozesse und Urteile II ; Berliner Gynäkologen-Prozess (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.04).

38 Kerscher, Helmut (1984): Wenn dem Opfer der Prozess gemacht wird. - In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 29.09.1984, See Pressedokumentation: Vergewaltigung : exemplarische Prozesse und Urteile II ; Berliner Gynäkologen-Prozess (FMT Shelf Mark: PD-SE.03.04, Kapitel 2 Debatte über Vergewaltigungsprozesse).

39 Erfahrung - Debatte - Veränderung : 10 Jahre bff ; 2005-2015. - In: bff Frauen gegen Gewalt e.V. [Hrsg.], p. 20f.. Retrieved from www.frauen-gegen-gewalt.de/id-10-jahre-bff-broschuere.html [PDF-Dokument].

40 Hat sie wirklich Nein gesagt? (2016). - In: EMMA-Online, 04.07.2016. Retrieved from: http://www.emma.de/artikel/hat-sie-wirklich-nein-gesagt-332983

41 Streitsache Sexualdelikte : Frauen in der Gerechtigkeitslücke ; Dokumentation zum Kongress des Bundesverbandes Frauenberatungsstellen und Frauennotrufe (bff) am 2. September 2010 im Roten Rathaus Berlin (2010). - Bundesverband Frauenberatungsstellen und Frauennotrufe (bff) [Hrsg.]. Berlin : o.V. (FMT Shelf Mark: SE.03.250). Also retrieved from: https://www.frauen-gegen-gewalt.de/de/streitsache-sexualdelikte.html

42 Ibid., p. 10.

43 Ermittlungsverfahren wegen Verdachts der schweren Freiheitsberaubung gegen frühere Partnerin des Wettermoderators K. (2017). - Staatsanwaltschaft Mannheim, 22.09.2017, [Press Release]. - Retrieved from: tinyurl.com/yc4ulva3

44 Louis, Chantal (2014): Petition : Nein heißt Nein! - In: EMMA-Online, 19.09.2015. Retrieved from http://www.emma.de/artikel/petition-nein-heisst-nein-herr-minister-330593

45 Ibid.

46 Mainzer Erklärung : Beschluss des Bundesvorstands der CDU Deutschlands anlässlich der Klausurtagung am 8. und 9. Januar 2016 in Mainz. Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU) [Hrsg.], p. 9. Retrieved from: https://www.cdu.de/system/tdf/media/dokumente/2016_01_09_mainzer_erklaerung.pdf?file=1

47 See Eine Revolution für die Frauen!. - In: EMMA, 07.07.2016. Retrieved from http://www.emma.de/artikel/eine-revolution-fuer-die-frauen-332995

All internet links were last accessed on 06.10.2017.

Selective Bibliography

Documents online

Recommendations

Brownmiller, Susan (1978): Gegen unseren Willen : Vergewaltigung und Männerherrschaft. -

Carroux, Ivonne [Übers.]. Frankfurt am Main : Fischer (FMT Shelf Mark SE.03.164).

Brückner, Margrit (1983): Die Liebe der Frauen : über Weiblichkeit und Mißhandlung. - Frankfurt am

Main : Verl. Neue Kritik (FMT Shelf Mark SE.01.006).

Schapira, Alisa (1977): Die Rechtsprechung zur Vergewaltigung: über die weit gezogenen Grenzen

der erlaubten Gewalt gegen Frauen. - In: Kritische Justiz 10, Nr. 3 (FMT Shelf Mark SE.03-a).

Tribunal Gewalt gegen Frauen : Frauen kämpft gegen Mißhandlung in der Ehe,

Abtreibungsverbot, Frauenlohngruppen und Hausarbeit, Frauenfeindlichkeit in der Werbung,

Erziehung zur Duldsamkeit (1978). - [o. O.] : Selbstverl., o. A. (FMT Shelf Mark SE.01.040).

FMT Press Documentation

Press Documentation on Rape: PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Selected FMT-Sources (lists)

FMT literature selection Rape: PDF-Download

EMMA article Rape: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Sexual Harassment - the Long Way to Sex Crime Legislation

Sexual Harassment - the Long Way to Sex Crime Legislation

Sexual harassment in the workplace became a public issue in Germany in the late 1970s, studies and debates have followed until it finally became a part of the sex crime legislation. › mehr

Sexual Abuse - When Crime Begins Within the Family

Sexual Abuse - When Crime Begins Within the Family

In 1978 feminist magazine EMMA first broke the silence of a long-held taboo: sexual abuse. 5 years later the self-help group Wildwasser and the first girls’ refuge were established. › mehr

Women's Refuges - Protection from (Sexual) Violence

Women's Refuges - Protection from (Sexual) Violence

Beginning in the mid-70s, the women’s movement made the dramatic extent of violence by men against their own wives and children public and launched the first women’s refuges. › mehr