As the women’s movement gets under way, the number of female judges, prosecutors, and lawyers is in the single digits. The law is almost exclusively administered by men. Feminists analyse that, in addition to already familiar “class justice”, there is also a “male justice” that has an effect on verdicts – in particular, with respect to murder and sex crimes. Traditional and newly-established networks for female lawyers founded over the course of the women’s movement manage to transform discriminatory laws to the point of appending the following central passage to Gleichstellungsartikel 3 of the German Constitution: “The state promotes the effective enforcement of equal rights for women and men and is working to eliminate existing disadvantages.” In 1994, Jutta Limbach is the first women and self-confessed feminist to become president of the Federal Constitutional Court. Today almost every second judge is female.

1970: Facts and Figures

The proportion of women in legal professions is in the single-digit range: 6% of judges, 5% of prosecutors, and 4.5% of lawyers are female.1

November 1972: The First Female Federal Prosecutor

Anne-Marie Hofmann, senior prosecutor at the Federal Court of Justice in Karlsruhe, is sworn in as the first female federal prosecutor. Hofmann – who was born in Stuttgart and studied law in Münster and Heidelberg – will remain the only female federal prosecutor in the FRG for 12 years.

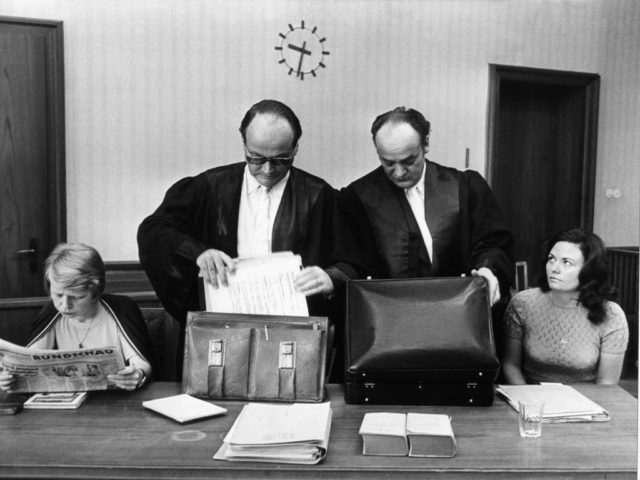

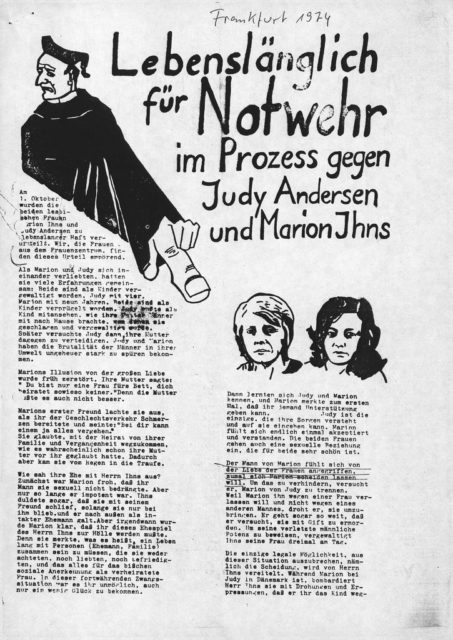

1 October 1974: Murder Trial Against Lesbian Couple

1 October 1974: Murder Trial Against Lesbian Couple

The sentence is read at the Itzehoe district court in the murder trial of Marion Ihns and Judy Andersen. The two women – who were having an affair – are sentenced to life in prison for employing a contract killer to murder Ihns’s husband. The court does not consider any factors that could be regarded as mitigating. Both women were victims of sexual abuse in their childhoods. Wolfgang Ihns had not only abused his wife for years, but he had raped her and forced her to have an abortion. The court grants the press and public access for the duration of the trial. The proceedings are accompanied by a lurid media campaign: for example, the Bild writes “if women only love women, a crime often occurs”.

Already during the trial, women’s groups from across Germany protest in front of and inside the court against the conduct of the case and the media’s smear campaign: “The murder charge is an excuse – lesbian love is in the pillory!” is written on their t-shirts. In an article for konkret Alice Schwarzer writes: „For weeks, a male-dominated press has been celebrating turning a murder trial into a lesbian trial.“3 136 female and 36 male journalists lodge a complaint against the defamatory reporting with the Deutscher Presserat. This is the first feminist protest against a (gender-)political case.

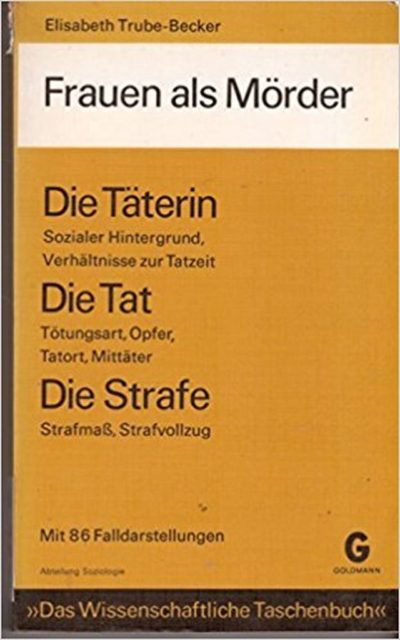

1974: Fate of Female Inmates

In her study Frauen als Mörder4 the Düsseldorf-based forensic scientist Prof. Elisabeth Trube-Becker investigates the cases of 86 female inmates serving life in prison for murder at the Strafanstalt Anrath. It is the first systematic study of its kind in West Germany.

Trube-Becker – the first female professor of forensic science in Germany – arrives at astounding conclusions. For example, Trube-Becker concludes that wives are more likely to kill than single women; in nine out of ten cases, the victims are the women’s husbands or children. Two out of three perpetrators “had” to get married, and the majority had no education. While men kill in exceptional circumstances, women kill in “normal” situations. And women are punished more severely – and more rarely pardoned – than men for the same crime.

1976: Feminist law offices

The first feminist law offices are established in Berlin, Hamburg, and Frankfurt. In addition to representing women in divorce, custody, or rape trials, they collaborate on “women-orientated legal projects“.5 Thus, they develop divorce manuals and support the residents of the first women’s refuges, founded in late 1976 (see our text on women’s refuges).

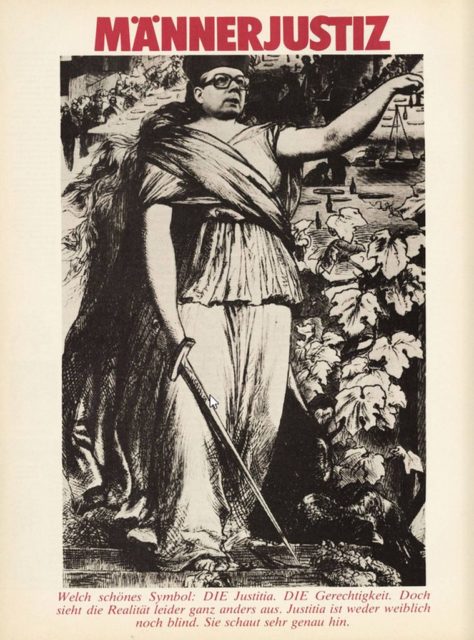

February 1977: Schwarzer’s Männerjustiz

In her text Männerjustiz,6 Alice Schwarzer analyses – on the basis of numerous examples and with reference to Prof. Elisabeth Trube-Becker’s study, among others – how lenient the legal system is with male murderers of women, especially if the men have killed their wives or lovers. Schwarzer writes: “The murder of a wife by her husband is, among other men, often considered little more than a petty crime“.7 This especially applies if “the perpetrator’s pride was hurt” by the victim. While male perpetrators are often handed short sentences, female perpetrators are frequently given unreasonably long, harsh sentences. “Male violence against women is so banal, commonplace. He can hit her every day, threaten to kill her, and no one will get worked up about it. And if he one day accidently kills her – well, it’s nothing more than a slip up. He simply went a bit too far. But if female violence is directed at a man, there’s outrage! Then male society sets a vengeful example.” Schwarzer further complains, again on the basis of numerous examples, about the “complicity of male justice and male media”. And she substantiates her claim that “the entire legal literature is evidence of deep-rooted sexism.“8

March 1977: The Underrepresentation of Women

Feminist lawyers establish that legal case studies in text books, working papers, and revision texts for academic study and legal training often transmit sexist and stereotypical representations of women. Vera Slupnik and Franziska Pabst determine in their empirical study Das Frauenbild im zivilrechtlichen Schulfall9 that women are plainly underrepresented in case studies. The women who do feature are, for the most part, defined by their relationships to men; the women without a male partner are often portrayed as either looking for a man or as quirky old maids. If the women are working at all, then they are employed in typically female professions as secretaries, cleaning ladies, or saleswomen.

1 July 1977: The Family Law Reform

The great family law reform comes into force. Among other things, it abolishes the previously extant “Schuldprinzip” in divorce law. Divorced spouses deemed “guilty” had absolutely no claim to maintenance payments. Wives were especially affected because they often had no, or only a very low, income and therefore could not afford to divorce. § 1356 BGB, which had obliged the woman to carry out the housekeeping – was similarly abolished: “The woman is in charge of the household. (…) She is entitled to work, insofar as this is compatible with her marital and familial duties.” Now the law reads: “spouses settle matters of housekeeping by mutual agreement.”(WDR keyword 1. July 1977)

The Deutsche Juristinnenbund (DJB) is significantly involved in this epochal reform as well as in other reforms that improve women’s legal standing. The family lawyer and SPD politician Lore Peschel-Gutzeit was the first chair of the Juristinnenbund at the time. Founded in 1948, the lobby organisation – which has the goal to “realise the equality of women in all areas of society” – had repeatedly fought for appropriate legal reforms since the post-war period. For example, already in 1958 the Deutscher Juristinnenbund had achieved by means of a constitutional complaint that the so-called paternal “Stichentscheid” (or “casting vote”) in family matters was abolished because it violated Article 3 of the Constitution (“men and women are equal”).

1978: Emma’s Lawsuit Against the Stern

The lawsuit initiated by EMMA (see our text on pornography) against the Stern for the portrayal of women as sex objects was also about changing prevailing law: at the time, there was a law that penalised racist images, but none that penalised sexist images. Advised by the lawyers Gisela Wild and Lore Maria Peschel-Gutzeit, the plaintiffs knew that they would lose the case on purely legal grounds; however, they won a moral victory. Judge Engelschall declared, that he understood the plaintiffs’ concerns: “In 20 or 30 years, the plaintiffs may perhaps win.” – However, 40 years later there still is no law against sexism in Germany (in contrast, for example, to the USA).

The first Jurafrauentreffen takes place in Frankfurt, Berlin, and Hamburg. The aim: to enable feminists in legal professions to network, exchange experiences, and discuss key issues like “violence against women” or “the woman’s role in family law”. 100 women take part.10

More and More Female Judges in 1982

More and more women are studying law. As reported by the Federal Statistical Office, the number of women studying law has risen by 70% since 1975. Every one in three law students is female.11 The number of female judges across all courts in the FRG has more than doubled when compared to 1970: up to 14.4%. Only in the federal courts in Germany is the number of female judges administering justice less than 5%.12

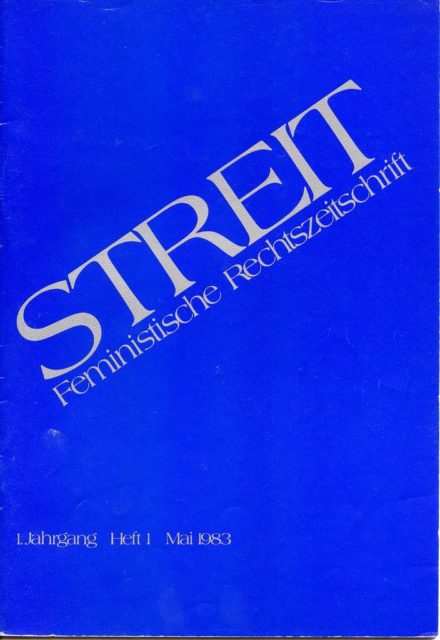

May 1983: Streit – Feminist legal journal

Inspired by the Jurafrauentreffen, female lawyers establish the feminist legal journal STREIT. It is published in Frankfurt. The editorial in Issue 1/1983 asserts: “The lean times are over; we have finally created our own forum: STREIT! Feminist legal journal! No more gruelling arguments when trying to integrate female-orientated approaches in critical and uncritical legal journals. No more male censorship of our ‘pseudo-legal’, ‘unscientific’, and generally ‘uninteresting’ minority positions.“13

July 1983: Sexism in Legal Books

Female lawyers denounce sexism in legal text books, and the media reports about the problem. The focus of media coverage is on legal works by the Berlin-based law professor Hermann Blei, who gives a gynaecologist the name “Frauenfeind”, a pimp the name “Himmelstoß”, and a young woman the name “Bertha Lüstlein” in his case studies. The Berlin-based court trainee Luise Morgenthal criticised the professor’s sexist choice of words in the journal Kritische Justiz, which – Morgenthal argues – sound as if they had “sprung from the lewd fantasy of an amateur pornographic writer“.14 Other text books, or rather professors, use similarly sexist example names. At the same time, male lawyers frequently make public statements that call the legal reliability of women into question.15 For example, the article Die Frau als Zeugin in the Handbuch des Strafverteidigers claims that false statements and perjury are typically female offences.16

1984: „Bubi“ Scholz-Process

The former boxer Gustav “Bubi” Scholz is sentenced to three years in prison, one year of which is to be served on probation, for the fatal shooting of his wife Helga Scholz. Scholz had shot his wife through the glass door of their guest toilet, where she had locked herself. The judges convict Scholz neither of murder, nor of manslaughter, but of negligent homicide. Scholz receives his wife’s life insurance: 650,000 DM. The court and the media are sympathetic to the former boxer, who felt neglected and rejected after his retirement from sport. EMMA cites the reactions in the media: “It had to end this way because ‘she didn’t listen’, because ‘she didn’t want to have sex anymore’, because ‘she called him Bubilein’, because ‘she was successful and he wasn’t’, because she was a ‘high school graduate’ and he was only a ‘boy from the neighbourhood“.7 Alice Schwarzer analyses the function of the sensational case and lenient judgement in her essay Politische Prozesse :“ That the Scholz trial was so celebrated and talked about in 1984 was not only because of its famous defendant. It was also because the ‘Bubis’ of the nation did not want to hear any more talk about ‘marital violence’ (…) Yet ‘everyone knows’ that ‘after 29 years of marriage, it can get a bit rough sometimes’ ‘ (Der Spiegel)“.18 The journal STREIT also writes about “the way the perpetrator metamorphosed into the victim in the German press in the Gustav ‘Bubi’ Scholz case”.19

June 1985: Feministischer Juristinnentag

At the 11th Jurafrauentreffen, the participants decide to rename the event Feministischer Juristinnentag.20 The Feministische Juristinnentag is the institution for German-speaking jurisprudence and since 1986 takes place each year at different venues. Lawyers and judges as well as students, jurists, and legal gender activists meet to discuss and develop feminist strategies for legal policy.

February 1986: Wassermann-Scandal

Meanwhile, women make up almost 15% of all judges and approximately 30% of new hires. Since there are disproportionately many female graduates with good final marks, Rudolf Wassermann – president of the Intermediate Court of Appeal in Braunschweig – suggests lowering the qualification requirements for judicial office. In this way, Wassermann hopes to prevent that “in the future mainly women will be working for the judiciary“.21 Wassermann’s suggestions cause a scandal, especially as the lawyer claims that women working for the judiciary “simply cannot achieve what men achieve” because they are burdened threefold: at work, as a wife, and as a mother. Wassermann would instead prefer that women “are able to have and raise their children in peace”. The Deutscher Juristinnenbund describes the proposals – which are partly common practice – as a “scandal“.22

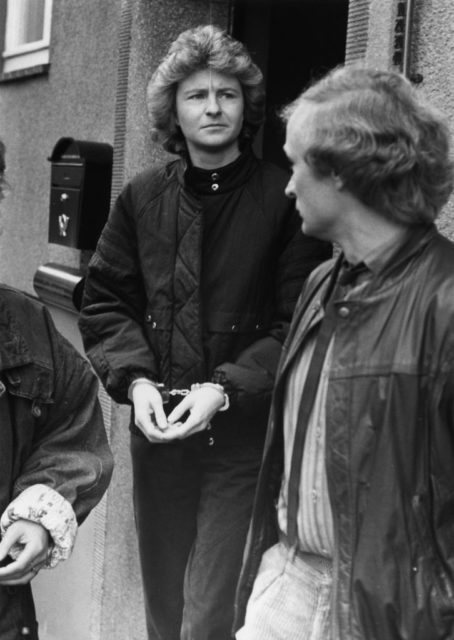

27 October 1986: „Rabenmutter“ Monika Weimar?

Monika Weimar (later div. Böttcher) is arrested on suspicion of murdering her two daughters; she is convicted once, acquitted once, and finally sentenced to life in prison after a trial based on circumstantial evidence. Monika Weimar had always maintained her innocence.23 Although Monika Weimar’s husband and the father of her children Reinhard Weimar also falls under suspicion, the investigation concentrates on the children’s mother, who had seriously violated gender conventions in her hometown Philippstal, Hessen. The trained nursing assistant had left her marriage, started to work again, and was in a relationship with an American soldier. Alice Schwarzer analyses: “Thus, the subject of the trial was not just the children’s deaths, but also the mother’s way of life. A totally normal woman from a conservative background who suddenly doesn’t function as expected.” “The ‘slut’ is certain to earn the scorn of all ‘cuckolded’ husbands, but also of all those women who dare not even dream of leaving.“24 The media coverage of the Weimar trial is huge, and many consider the “Rabenmutter” to be guilty. Gerhard Mauz from the Spiegel and Gisela Friedrichsen, then court reporter for the FAZ, lead the rush to condemn Weimar. Monika Böttcher was released from prison on 18 August 2006 after 15 years in prison.25

What Happens Next?

After German reunification, four female lawyers and politicians successfully append the following passage to Article 3 of the Constitution: “The state promotes the effective enforcement of equal rights for women and men and is working to eliminate existing disadvantages.” The state is thus constitutionally obliged to actively enforce gender equality. The four lawyers are Jutta Limbach (Senator of Justice in Berlin and later president of the Federal Constitutional Court), Lore Maria Peschel-Gutzeit (Senator of Justice in Hamburg), Heidi Merk (Minister of Justice in Niedersachsen), and Christiane Hohmann-Dennhardt (Minister of Justice in Hessen and later constitutional court judge).

Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger (FDP) becomes the first woman to be appointed Minister of Justice on 18 May 1992.

The self-confessed feminist Jutta Limbach becomes the first female president of the Federal Constitutional Court two years later in March 1994.

Female lawyers establish the European Women Lawyers Association (EWLA), a European lawyer’s network, in Berlin between 17-18 March 2000. The motto of the inaugural congress is: “Strategies Aimed at Establishing the Right to Equal Opportunities”. The EWLA was created on the initiative of Ursula Nelles, chair of the Deutscher Juristinnenbundes, and Cherie Booth, president of British Women Lawyers.

Lawyers set up the Feministische Rechtsinstitut (FRI), a nationwide platform for female lawyers that offers training and organises campaigns – in Hamburg in 2004. The FRI declares: “Power relationships in society are reflected in the law. The shift in gender relations is likewise visible in the law; here, we find the establishment and consolidation of traditional gender images and roles alongside approaches that foster equal treatment, equal rights, and the emancipation of women and men. Thus, in recent decades the power relationship between the genders has already been transformed by the law – although its successes are under constant threat and in the long run only selectively effective. Feminist lawyers have contributed significantly to this change. They analyse the gender bias in law and the structures that make it so difficult to effectively counteract the systematic social degradation and discrimination of women. But they also formulate demands and demonstrate how the law can combat stereotypes and prejudices to enable new, non-stereotyped gender relations.“26

In May 2014, the Minister of Justice Heiko Maas (SPD) sets up a commission of experts to draft proposals for a reform of the murderer paragraph § 211 in German penal code. One reason why a reform is necessary: the element of ‘treachery’ in the legal definition of murder results in women – who, for instance, commit a ‘tyrannicide’ after years of abuse at the hands of their husbands – being convicted of a per-definition ‘treacherous’ murder (i.e., poisoning or suffocation while sleeping). They are therefore by law automatically considered ‘murderesses’ and must be sentenced to life in prison. A husband, on the other hand, who abuses his wife for years and kills her with a blow to the head is typically (only) charged with manslaughter and receives a much shorter sentence (see appropriate article).

In 2014, 42% of judges are female. Even in the highest German court, the Bundesverfassungsgericht, ever third judicial office is held by a woman.

Sources

1 Schultz, Ulrike (1990): Wie männlich ist die Juristenschaft?. - In: Frauen im Recht. Battis, Ulrich

[ed.]. Heidelberg : Müller Juristischer Verlag, p. 322 (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.13.133-a, Obj. Nr.: 22543).

2 Erste Bundesanwältin ernannt (1972). - In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 08.11.1972, see also Pressedokumentation: Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ST.15.01, chapter 5).

3 Schwarzer, Alice (1974): Im Namen des gesunden Volksempfindens. - In: Konkret, Nr. 2, Heft 11, p. 11 (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.15-a, Obj. Nr.: 67913). See also Pressedokumentation: Mordprozess gegen Marion Ihns und Judy Andersen, 1973-1987 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-LE.11.07).

4 Trube-Becker, Elisabeth (1974): Frauen als Mörder : mit 86 Falldarstellungen und 34 Tabellen. -

München : Goldmann (FMT-Self Mark: ST.15.021).

5 Ewe, Petra; Pötz-Neuburger, Susanne (1983): Wie wir wurden, was wir sind. Zur Geschichte der Jurafrauentreffen Teil 1. - In: Streit, Nr. 1, p. 36, see also Pressedokumentation: Juristinnen, Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ST 15.01, chapter: Feministische Juristinnen).

6 Schwarzer, Alice: Männerjustiz (1977). - In: EMMA, Nr. 1, p.6 ff.. retrieved from: www.emma.de/lesesaal/47040

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Pabst, Franziska; Slupik, Vera (1977): Das Frauenbild im zivilrechtlichen Schulfall. Eine empirische Untersuchung zugleich ein Beitrag zur Kritik gegenwärtiger Rechtsdidaktik. - In: Kritische Justiz, Nr. 3, p. 242-256. retrieved from: www.kj.nomos.de/fileadmin/kj/doc/1977/19773Pabst_Slupik_S_243.pdf ) und Die Frau in juristischen Fallbeispielen. Mit Brigitte Brunft lebensnah und heiter zu juristischen Weihen (1979). - In: Göttinger Nachrichten nicht nur für die Frau, Nr. 2. For both texts, see Pressedokumentation: Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT- Shelf Mark: PD-ST.15.01, chapter 8).

10 Ewe, Petra; Pötz-Neuburger, Susanne (1983): Wie wir wurden, was wir sind. Zur Geschichte der Jurafrauentreffen Teil 1. - In: Streit, Nr. 1, p.36. See Pressedokumentation: Juristinnen, Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ST.15.01, chapter: Feministische Juristinnen).

11 Immer mehr Frauen wählen Jura-Studium (1986). - In: Weser-Kurier, 27.12., see Pressedokumentation: Juristinnen, Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD.ST.15.01, chapter 8).

12 Männerrecht (1985). - In: Die Zeit, 31.05., see Pressedokumentation: Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ST.15.01, chapter 8).

13 Editorial (1983). - In: Streit: feministische Rechtszeitschrift, Nr. 1, p. 2.

14 Morgenthal, Luise (1983): "August Geil und Frieda Lüstlein" : Der Autor und sein Tätertyp. - In: Kritische Justiz, Nr. 1, p. 65-68. retrieved from: www.kj.nomos.de/fileadmin/kj/doc/1983/19831Morgenthal_S_65.pdf und Herr Lustbold (1983). - In: Der Spiegel, Nr. 30. retrieved from: www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-14018116.html

15 Die Tageszeitung: Typisch männlich, 02.03.1983 und Sybille Uken (1983): Die Frau das einfältige Wesen. - In: Die Tageszeitung, Nr. 23, 12/83, see Pressedokumentation Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ST.15.01, chapter 8).

16 Die Frau als Zeugin. - In: Dahs, Hans (1983): Handbuch des Strafverteidigers, 5. neubearb. Auflage, Köln : O. Schmidt.

17 Unser Bubi (1984). - In: EMMA Nr. 9, p.7.

18 Schwarzer, Alice (1989): Politische Prozesse - von Weimar bis Memmingen. - In: EMMA, Nr. 4, p.6.

19 Oberlies, Dagmar (1986): Die Bubis: wie Täter zu Opfern werden. - In: Streit : feministische Rechtszeitschrift, Nr. 1, p. 3-8.

20 Borg, Dagmar; Walz, Claudia (1985): Der 11. Feministische Juristinnentag in Berlin. - In: Streit, Nr. 3, see Pressedokumentation: Juristinnen, Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ST.15.01, chapter 10).

21 Hoffnungslos überfordert (1986). - In: Spiegel, Nr. 7 (10.02.1986), p.50. retrieved from: www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-13516959.html ) und Dumme Juristen (1986). - In: EMMA, Nr. 3, p. 44. For both texts, see Pressedokumentation: Juristinnen, Frauen in der Justiz, 1913, 1954-1996 (FMT-Shelf Mark: PD-ST.15.01, chapter 9).

22 Hoffnungslos überfordert (1986). - In: Spiegel, Nr. 7 (10.02.1986), p. 50. retrieved from: www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-13516959.html )

23 Böttcher, Monika (1997): Ich war Monika Weimar. - Köln : Kiepenheuer & Witsch (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.15.087).

24 Schwarzer, Alice (1989): Politische Prozesse - von Weimar bis Memmingen. - In: EMMA Nr. 4, p. 4-6.

25 Friedrichsen, Gisela: Ende eines Justizdramas: Zweifache Kindsmörderin Monika Böttcher ist frei. – In: Spiegel Online, 18.08.2006. retrieved from: www.spiegel.de/panorama/justiz/ende-eines-justizdramas-zweifache-kindsmoerderin-monika-boettcher-ist-frei-a-432435.html

26 Feministisches Rechtsinstitut (2017): Wozu ein Feministisches Rechtsinstitut?. retrieved from: www.feministisches-rechtsinstitut.de/wir_ueber_uns.htm

Selective Bibliography

Sources online

Annette Ramelsberger (2013): Die neue Rechtsordnung. - In: Süddeutsche Zeitung Magazin, Nr. 40.

Blog zum Thema sexistische Inhalte im Jurastudium: "Juristenausbildung. Üble Nachlese".

Recommendations

Trube-Becker, Elisabeth (1974): Frauen als Mörder: mit 86 Falldarstellungen und 34 Tabellen, München : Goldmann (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.15.021).

Schwarzer, Alice (1977): Männerjustiz. - In: EMMA, Nr. 1, p. 6 - 14.

Kohleiss, Annelies (1985): Frauen im Recht. - In: EMMA, Nr. 9, p. 30 - 31.

Jones, Ann (1986): Frauen, die töten. - Drolshagen, Suhrkamp (FMT-Shelf Mark : ST.15.028).

Oberlies, Dagmar (1995): Tötungsdelikte zwischen Männern und Frauen : eine Untersuchung

geschlechtsspezifischer Unterschiede aus dem Blickwinkel gerichtlicher Rekonstruktionen. -

Pfaffenweiler : Centaurus (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.15.079).

Frauen in der Geschichte des Rechts : von der Frühen Neuzeit bis zur Gegenwart (1997). - Gerhard, Ute [ed.]. München : Beck (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.13.162).

Hexenjagd : weibliche Kriminalität in den Medien (1998). - Henschel, Petra [ed.] ; Klein, Uta

[ed.]. Erstausg., 1. Aufl. - Frankfurt am Main : Suhrkamp (FMT-Shelf Mark: ME.03.055).

Pasquay, Heide (2002): Alle Richter bleiben Brüder : der alltägliche Sexismus im Rechtsbetrieb. - In: Menschenrechte sind auch Frauenrechte. - Nagelschmidt, Ilse [ed.] ; Schötz, Susanne [ed.] ; Kühnert, Nicole [ed.] ; Schröter, Melani [ed.]. Leipzig : Leipziger Univ.-Verl. (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.13.225-a, Obj. Nr.: 61685).

Juristinnen in Deutschland : die Zeit von 1900 bis 2003 (2003). - Deutscher Juristinnenbund (DJB) [ed.]. 4., neu bearb. Aufl. - Baden-Baden : Nomos (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.13.038-2003).

Flügge, Sibylla (2003): 25 Jahre feministische Rechtspolitik - eine Erfolgsgeschichte?. - In: Streit : Feministische Rechtszeitschrift Nr. 2, p. 51 – 62 (FMT-Shelf Mark: Z-F011:2003-2-a, Obj. Nr.: 49447)

Schultz, Ulrike (2004): Richten Richterinnen richtiger?. - In: Landesweite Aktionswoche : Frauenbilder ; vom 25. Februar - 24. März 2005 in Nordrhein-Westfalen. - Ministerium für Gesundheit, Soziales, Frauen und Familie

MacKinnon, Catharine A. (2005): Women's lives, men's laws. - Cambridge, Mass. [u.a.] : Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press (FMT-Shelf Mark: FE.10.050)

Frauenrecht und Rechtsgeschichte : die Rechtskämpfe der deutschen Frauenbewegung (2006). - Meder, Stephan [ed.] ; Duncker, Arne [ed.] ; Czelk, Andrea [ed.] ; Köln [u.a.] : Böhlau (Rechtsgeschichte und Geschlechterforschung ; 4) (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.13.238)

Röwekamp, Marion (2011): Die ersten deutschen Juristinnen : Eine Geschichte ihrer Professionalisierung und Emanzipation (1900 - 1945), Köln, Wien : Böhlau (FMT-Shelf Mark: ST.13.266).

Schultz, Ulrike (2012): Frauen in Führungspositionen der Justiz. - In: Deutsche Richterzeitung, Nr. 9, p. 264 - 272.

Ulrike Lembke (2016): Feministische Juristinnen in der Bundesrepublik. Interview mit Susanne Pötz-Neuburger, Sibylla Flügge, Barbara Degen und Malin Bode. - In: Kritische Justiz (ed.): Streitbare Juristinnen: Eine andere Tradition, Baden-Baden : Nomos, p. 617 - 642.

Journals

Zeitschrift des Deutschen Juristinnenbundes (djbZ), Nomos Verlag, ISSN 1866-377X (FMT-Shelf Mark: Z-F086).

Streit: Feministische Rechtszeitschrift, Fachhochschulverl. ISSN: 0175-4467 (FMT-Shelf Mark: Z-F011).

Press documentation

Press documentation "Law&The Dispention of Justice": PDF-Download

The FMT press documentation is thematically structured and indexed. It comprises articles of the general public press, feminist press and other documents, such as leaflets and archival documents.

Further FMT collections (selection)

FMT-literature Law&The Dispention of Justice : PDF-Download

EMMA-article female justice: PDF-Download

EMMA-article male justice: PDF-Download

Related Topics

Lesbian and Feminist - Female and Homosexual: Becoming Visible

Lesbian and Feminist - Female and Homosexual: Becoming Visible

Female homosexuality was still a taboo at the beginning of the 1970s. The women’s movement made lesbians visible. › mehr

Abortion – a Legal Right? Feminists Vs. All

Abortion – a Legal Right? Feminists Vs. All

The struggle for abortion rights sparked the emergence of the Women's Liberation Movement in West Germany 1971. › mehr

Fighting Sexual Violence and (Marital) Rape

Fighting Sexual Violence and (Marital) Rape

In the mid-1970s, the women’s movement brought the epidemic of sexual violence to the public’s attention. The women fought for a sex crime law reform, that finally came through 1997 and 2016. In Germany today the principle rules: No means No. › mehr